Oh, 2001, when I was someone else, becoming someone else. In my piece on 2000, I told how I had been employed on contract in Ontario's public sector IT department, only to be laid off in August. This didn't bother me too much, because I soon had an opportunity to house sit on Pender Island, British Columbia, for the winter. After publishing two short story books (1999, 2000), I planned to write a novel "about space aliens and the death of the family." I'd made a start on it at a writing residence on Toronto Island in September, where I met A., who would come visit me on Pender.

So, 2001 started with me home alone on Pender Island, minding the house, and writing as much as I could. I planned to have 12 chapters in the novel, each about 5,000 words. The novel had four main characters, each a member of the family, and each character had three chapters. When my hosts returned in March, I had a draft completed. I packed up my (minimal) belongings and said, gracias, and vamoose. I made my way to Vancouver, where I bunked one night on the lower East side with a writer I knew only through online connections. My plan was to catch a very early bus via Calgary to Saskatoon. There was a pay phone on the corner outside his place. In the middle of the night I collected my bags and crawled down the stairs, out the door to the phone. In my memory, within view were three police cars and much more activity than should reasonably be happening at 4:00 in the morning. I was using the phone to call a cab, to get to the bus station. I thought, is a cab going to come here? It did.

I had taken the bus from Toronto to Vancouver and back to Toronto in 1996, so I was aware of what I was about to do again. My first stop out of Vancouver was Saskatoon, where the publisher of my book, Only A Lower Paradise (Boheme Press, 2000) had arranged for me to read at Chapters.

I had described the scene of the sun arising over the prairie outside Calgary in my story “Day Two, Saskatchewan” (from Thirteen Shades of Black and White, 1999), where I’d imagined the following scene:

The kid was asleep, so I poked him

“Look.”

“What?” His eyes were still closed.

One lid came up, then the other. He looked across me and out the window. Red, orange, and yellow layers of sky piled on the horizon. He turned to his left, stared out over more fields, more sky.

“We’re surrounded,” he said.

…

The world has a lot to offer; that’s what I wanted to teach the kid. The world has a lot to offer if you know where to look.

As noted earlier, I had lived in Saskatoon from 1992-94, and I thought I would see some of my old friends at my reading. I had been back to Saskatoon in 1996 and 2000. My return in 2001 is the last time I've been there. It seems to me, two people I knew came to the reading in Saskatoon: L. and her mother. I don't remember where I stayed on that visit, which was short. Quickly, I was back on the bus and heading to Winnipeg, where I stayed with an old family connection.

Winnipeg was bizarre. I was booked to appear on the local breakfast television show, then later that day at a Chapters. I can't, looking back, imagine how slow a news cycle it must have been in Winnipeg for me to be one of the morning TV features. The host, gratefully, seemed to know something about the book, but I am not built for sound bites and image-making. I am an introvert and observer. I felt like I was outside my body watching myself being interviewed on TV, not knowing what was happening. The host would later become a prominent commentator on a sport cable channel. That was a dude made for TV. Me, not so much. I think I also appeared in a classroom at Canadian Mennonite Bible College, though I can't remember how that happened. Only A Lower Paradise is a speculative, future-oriented novella, where the space-time continuum breaks and angels appear and act as, essentially, therapeutic guides. I wrote it as an undergraduate, and it's in the spirit of Vonnegut or Richard Brautigan. The Mennonites in the Bible College were not on that wavelength LOL.

From Winnipeg, I headed for Thunder Bay, where a friend I'd met at the Toronto Island retreat set up a coffee shop reading. I also made a Chapters appearance, attended by a very distant cousin of mine, whom my father had dug up. She was an older lady and extremely excited to meet me, an author (holy smokes!). The people at Chapters, however, were less happy to see me. They'd prepared coffee and snacks and no one showed up, and they wanted to know who was going to be paying for all of this? You've been talking to my publisher? I asked. Yes, they had. Well, keep doing so! One story I remember from Thunder Bay was how my friend's neighbour was a tough and violent man, who owned a tough and violent pit bull. Everyone was afraid of that dog. No one knew what to do about it. Talking to the neighbour was out of the question. Someone had an idea. They got an air gun and used chocolate chips as ammunition. When the dog was making ruckus in the yard, the gunman popped him, and he soon learned to settle down.

From Thunder Bay, I travelled straight through to Toronto, surviving on bagels and water. My strategy was to keep things simple for my gut and basically drift in and out of sleep. I remember Sudbury at 5:00 a.m., thinking “we’re almost there, only 5 more hours.” Time was indeed a flat circle ... I had taken James Joyce's Ulysses to the West Coast and back, thinking I'd have plenty of reading time, but I didn't tackle even a single page. I crashed at my parents' place, once back in T.O., then reconnected with A., and started to look for work. One of the first places I called was the temp agency who'd employed me in 1999. Did they have anything? Yes, they did. In fact, the project I'd been laid off from about eight months earlier needed someone just like me: a writer with basic webpage skills. Okay, I said. I'll take it!

I had been continuing to publish/edit The Danforth Review (TDR) while I was on Pender. Pretty much everything, except the receiving and distributing of books to reviewers, took place online. I was one of the OG remote workers, though was it work? It didn't pay. It was a labour of love and intellectual curiosity. The first HTML issue had been in September 1999, and subsequent HTML issues appeared in December 1999, March 2000, and September 2000. At that point, I migrated all of the content to a Microsoft Frontpage Web. That might sound technical, but it just meant that I started using MS's Frontpage program to manage the website. In practical terms, it became easier. It also meant that TDR went from being an online periodical, to being a website. That is, instead to uploading new content, say, quarterly, I started uploading new content a couple of times a week. The "issues" became bi-annual: new fiction and poetry selected from submissions. On a day-to-day basis, though, the website was singular. It now included all archived content and started to get bigger and bigger. What had started on a lark, started to be a project that required managerial strategy, planning, and coordination.

While this technical transition took place for TDR, it remained an Internet 1.0 publication. The world was still years away from the iPhone, Facebook, Twitter and social media. I never dabbled in Myspace or Tumbler, so I cannot comment on them. If I were starting TDR today, I would likely do it as a Substack and use Submittable to manage submissions, which I did later for TDR (for many years, all communications were done via email, which meant staying on top of a lot). The idea was that TDR could be a lit mag, just on the internet, but when it became a "website" it tipped towards something else. A creative and innovative young person starting something today might just as easily now start on TikTok, doing video reviews, interviews, promos, and hot takes, but TDR was print-based without regret. It was of its moment, one perhaps surprisingly short-lived in retrospect.

I funded all expenses for TDR for the first few years: hosting fee, domain registration, mailing costs. It was bare bones, but so was my bank account. It was in 2002, I believe, that the Canada Council started to provide some funding for electronic publications. Until 2009, when TDR closed for hiatus, the CC gave TDR about $6,000 per year. TDR, then, paid $100 per short story or poem, $100 for a "feature" (interview/article), and $0 for reviews. TDR published about 30 stories/poems per year and roughly two features per month: accounting for $5,400. The remaining money covered the hosting fee, domain registration, mailing costs, plus stipend for the editors: me (overall/fiction), Geoff Cook and Shane Neilson (poetry), the book review editor (held by a couple of folks, including K.I. Press, also mostly me). TDR's unique visitor counts from the internet servers counted in the tens of thousands, but I never trusted those numbers. Who knows how many people visited? All I knew for sure is, folks kept submitting fiction and poetry for consideration, and publishers kept burying us in books.

I didn't publish much in 2001, outside of TDR. Two short stories and five reviews:

Short stories:

“How Many Girlfriends.” The New Quarterly.

“The Coming Anarchy”. &.

Reviews (all in Quill & Quire):

Feb 2001. Ice Lake by John Farrow.

April 2001. Benedict Arnold: A Traitor in Our Midst by Barry K. Wilson.

June 2001. Sticks and Stones: A Randy Craig Mystery by Janice MacDonald.

July 2001. Unsung Courage: 20 Stories of Canadian Valour & Sacrifice by Arthur Bishop.

Sept 2001. Memos to the Prime Minister: What Canada Could Be in the 21st Century. Ed., Harvey Schachter.

For TDR, I reviewed and selected the fiction submissions. I would try to select between four and six out of, generally, 200 submissions per issue. I found nearly all of the submissions to be written well enough, hard to distinguish in quality one from the other. I kept looking for stories that stood out from the crowd, had a distinct voice or facility with language, or were particularly odd in one way or another, anything with extra spark. I found I could quite easily get the list down to the final 20, but then it became difficult. At that point, I would try to find a batch that went well together, which mostly meant were distinct from each other. For example, not four stories about childhood or not all relationship dramas. Also, I tried for a gender balance. I tried to read the stories without looking at any biographical information. I wanted to encounter each story fresh with as little outside information as possible. I selected all kinds of stories, some more sci-fi, some hard boiled, some ironic, some sentimental, some full of existential dread. If anything, I hoped, ultimately, my selections would defy any pattern.

There was probably more of a pattern in the writers I interviewed for TDR, especially initially. I was very keen to interview Mark Anthony Jarman, for example. I had reviewed his collection 19 Knives (2000) for Quill and Quire and wanted to probe this writer who had produced such scorching prose. I still remember some of the things he said, images burned in my brain, like propane on a Texas porch.... such as reading John Cheever on a bus. Also, that I asked him about his work "seems to argue with the standard tropes of "Canadian literature." He replied, "I hope it does."

Work that argues with standard tropes is work I wanted to support, then — and now. Why else art?

Other writers I interviewed in 2001 were:

Later, perhaps at an event for Goran Simic's 2005 short story collection, Yesterday's People (2005), I spent part of an evening with Leon and the inestimable Constance Rooke at a below-street-level bar on College Street, hosted by Dan Wells' Biblioasis, I believe.

Now, when I think of my life in 2001, I see different bubbles. There was the novel I was trying to write; and some imagined life with future books. There was the need to have a job to pay rent. There was TDR, which kept me connected to "the writing community," whatever that meant, and allowed me to pursue my intellectual and aesthetic curiosities in ways that wouldn't have been otherwise possible. I took advantage to interview writers, for example. I remembered asking one of my profs after I finished my MA at the University of Toronto, "How am I going to continue my education?" I wanted out of the academy, but I didn't want to stop learning. TDR was, in many ways, my PhD project, independently implemented. Finally, there was the sphere of my family. I was grateful that my parents were alive and well. My brother and sister-in-law were in Toronto with my then toddler nephew. I reconnected with A., and all seemed well. What else could I want? I was turning 33 that year, the Jesus year, more than one person said to me. Hey, man, everything's great!

In one of my first weeks at the new job, this time in the communications branch, not the IT branch, my manager asked me if I could write a speech. They needed someone to write a speech. No dummy, I said, yes, of course, though I never had. About what? Human resources renewal. I asked if there was background material I could review. Thankfully there was, plus they provided me with examples of previous speeches. I banged out a draft, which made its way to the Director, who later sought me out. "You wrote this?" Yes. I learned she had said to my manager, "The IT guy wrote this?" Yes. Apparently it was good, not only better than they expected, but better than they were used to getting. The Director would become my greatest supporter and ally. There was no way, now, she was letting me get away. They bought me out of my temp agency contract and put me on a fee for service contract. They had a plan, though I didn't learn until later what it was. It would come to fruition a year later, when the Ontario Public Service Employees Union went on strike for eight weeks. More on that another time.

A. was my age, with a master's degree in public administration. She had VP title with a polling company. When I had met her the previous summer, she was working for Artscape, the non-profit entity that managed space for artists. She'd quit a senior job with a polling company prior to that, because she wanted more artsy things in her life and less of a professional grind. But the non-profit world proved to be just as full of administrative BS, and so she'd returned to a higher paying, longer work hours, career path. But she kept an easel in her apartment fixed with a work in progress and paid rent for a small studio space, which she found less and less time to visit. Her life, it seemed to me, was very like my own: art/life. We were soon together nearly every day. She had an apartment at St. Clair, west of Yonge, and I had taken an apartment on Vaughn Road, north of St. Clair, west of Bathurst. My mother wondered what I was doing "all the way out there," but it was less than a 30 minute walk from my apartment to A’s.

I will take a moment for an aside to say that Hemingway once lived on Bathurst not far from my place on Vaughan Road, a fact I wasn't ignorant of at the time, but I wasn't sure what to do with it. The building where Ernest lived is now called The Hemingway.

As I said, by mid-2001 the whole state of my life seemed great. Let's just keep this going, shall we? Full steam ahead.

September 11, 2001, the earth shook.

My account of that day begins the way I've read many others began. It was a beautiful day, bright, sunny, clear blue skies. I arrived at the office, slightly late. It was a Monday? I went straight to my office and fired up my computer. Folks were gathered in the TV room, but I wanted to get myself sorted. My manager came to my door and asked if I'd heard. No. He told me a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. Okay, I said. I imagined what I've read many others imagined. It was a small plane, lost, mechanical issue, strange tragic story. I didn't rush to the TV room. Then he came back. A second plane had crashed into the World Trade Center, the other tower. I thought what I've read many others thought in that moment: this is not a coincidence. Suddenly, there was a pattern. I went to the TV room, I went back to my desk, I pulled up CNN, started searching for news. Planes across North America were being grounded. Up to 10 airplanes had been hijacked. Wild rumours proliferated. I don't remember much about the plane in Pennsylvania or the Pentagon, but I was in the TV room when the towers fell and the dust clouds rushed down New York City streets. No one was doing any work. By mid-afternoon we were told to go home. A. and I agreed to meet at the Manulife Centre at Bay and Bloor because there was a blood donor clinic, and the word was that massive quantities of blood would be needed. By the time we got there, a long line had formed. We decided to go home, to her place, where we sat on the couch and watched the repeating visuals on the television. What was going on? The world was ending, surely. One version of it anyway. War, it was quickly evident, was coming, was here.

For the remaining months of 2001, locally in my life, the status quo remained. I worked, TDR continued, I spent nearly all of my free time with A., and we started to wonder, should we move in together? For me, I wanted to see how the holiday season went, how the stress of families gathering would go. It went okay, requisitely awkward, nothing explosive. A.'s sister was married to a Polish-Canadian guy, whose elderly Polish father came to the family gathering. His English was not great, and frankly he was patronized by many people there, but I spoke with him and learned some things about him, and when I told those things to A. later she could hardly believe it: "You got him to talk!" Well, yeah. I asked him some questions. Later, A. and I fought and broke up for a couple of days, then we reunited after New Year's and seemed stronger than ever. But that's a 2002 story for next time.

What of the novel draft I had written in B.C.? I knew it wasn't great, but I thought it had promise. I was hoping I could find an editor who could see what it was missing and help get it to a better place. I sent it to my first publisher, Turnstone Press, and they were not interested in it. I'm not sure I sent it anywhere else. As many writers do, I had turned against the work, but I was also hopeful that I would find renewed interest in it, sometime later. This has never happened.

With time devoted to work, my relationship, and TDR, I was writing less and less. When I did think about my writing, I was contemplating how to "get to the next stage," whatever that meant. I didn't know what it meant, but I also felt confidence that such a stage existed. In the past decade, I had grown a lot as a writer, and I anticipated the next decade would include more growth, steady growth along a similar path. This was not to be the case, though. Looking back, now, I see that there was growth, but not along the same or similar path. "What I was doing" became less clear, not more clear; it became more confusing, not less confusing; it became more beyond my control, not open to my manipulation. Increasingly, I learned to trust a few words from Douglas Glover, about how literature "opens outward into mystery."

That phrase comes from Glover's essay collection, Notes Home from a Prodigal Son (1999), and I used it in a question I put to him in our 2001 interview:

TDR: In Notes from a Prodigal Son, you write: "My apprenticeship ended with the realization that the goal of literature is not simply truth, which is bourgeois and reductive, but a vision of complexity, an endless forging of connections which opens outward into mystery" (166). Perhaps you could briefly chart the progression of your apprenticeship, including the role "Mikhail Bahktin and his ideas about discourse and the dialogic imagination" (Prodigal Son, 37) play as an ongoing literary influence in your work.

GLOVER: My life has been an apprenticeship for whatever comes next, though I do periodically think I have reached some more definitive threshold of existence only to find later that it was just another painful learning experience (a lot of these). But in the process I find certain writers and thinkers to be companionable. Bakhtin, when I read him, seemed to be saying things that made sense of what I had been trying to puzzle out about writing and my life. As he says, language is war. Most of my life I've been fighting a war against the discourse of rural Tory provincialism, the Ontario miasma of my youth, and the various discourses that seemed allied with it: all sorts of conventionalisms, including all those perky new ones that keep popping up in the little villages of academic criticism and literary journalism. So much of what I say can be viewed as a moment in a battle: I am saying this is me and I am against that. It was a relief to read Bahktin who seemed to imply that I wasn't so dumb to feel embattled, that my sense of struggle, my dissatisfaction, even boredom, with certain ways of doing things, was natural. Bakhtin didn't show me something new, but he said everything again in a succinct and elegant way.

My question was as much grounded in my confusion about my own writing practice, as it was objective interest in Glover's writing or history. To put it another way, the questions Glover put to himself in his essays were often in parallel with questions I was asking myself. He had gotten there first, he had gotten way deeper than I had thought possible, and I thought here is a guide to help me go where I need to go.

Where was that? To follow the Don on a quest, chasing wind mills.

That's a metaphor, sure, but all the best answers are riddles.

I mean, look at that question. The dialogic imagination! This, more than anything, was the key I was seeking, a term that legitimized the multiverse. What jumps out at me now in Glover's answer now, is his sense of recognizing his inner struggle in Bahktin. I recognized my inner struggle in Glover. I had been formed, it seemed to me, by having come of age in Toronto in the 1970s and 1980s, via a close-to-downtown public school system, whirlwind of cultures, histories, and points of view, and it was this multiverse that I wanted to write about. One way of saying it would be: literature = everything everywhere all at once. It is not a question of which point of view should dominate, but how to articulate all of the points of view at the same time. Thus the focus on dialogue and Bahktin's notion of the carnivalesque (life is a carnival, believe it or not - The Band).

Narrative progresses by having different voices "talk to each other," exploring each other, pressing ahead in a sequence of tension and release. Not, however, to reveal, ultimately, truth; instead, to reveal mystery. Life moves on by being unresolved; from one complexity comes another; until death, the final complexity.

Focus on complexity makes illegitimate all simplicities and absorbs all positions into a perpetual conversation. It can rub down extremes, removing the sharp edges while also allowing difference and diversity to not only emerge but be central.

There was something about the carnivalesque, too, that seemed to align with the rise of the Internet and media becoming multi-polar. I was an Internet optimist and a McLuhan stan. More voices fed the democratic spirit, yes? Substack writers, focused on print, are kind of bringing that back, de-emphasizing the video/image which has taken over social media.

In the years after 2001, I would attempt to write short stories based on this theory, approach, foundation; it's my modus operandi. Focus on the quest, not the destination. Find ways to "write against" assumptions while also acknowledging them. I had always been pushing towards this, I believe, though I hadn't known it. In anything, previously, I had been pressing to get "closer to the real," but had found myself in a dead end. Opening "outwards into mystery" was a great gift and the major pivot in my writing life, at least one of them.

My life has certainly opened into mystery, more than once! But that's a different line of inquiry.

To give Glover his due, I'm going to focus on him and his work now. I've written a fair amount about his work already — collected recently on this blog here — so no doubt I will repeat myself below, but hopefully something new will come of it, too.

*

For biographical details on Glover, see his Canadian Encyclopedia entry and his Wikipedia entry, which notes his remarkable online magazine, Numero Cinq (2010-17). See also his personal website and his Substack, Out & Back.

Glover won the 2003 Governor-General's Award for Fiction for his novel, Elle (2003), and was nominated for the same award in 1991 for this short story collection, A Guide to Animal Behaviour (1991).

Glover’s work includes short story collections, novels, memoir, essays, and what I’ve going to call literary instruction.

*

Perhaps the best way to proceed is for me to discuss my favorite Glover bits, pieces, and moments.

Let's begin with the short story collections:

The Mad River (1981)

Dog Attempts to Drown Man in Saskatoon (1985)

A Guide to Animal Behaviour (1991)

16 Categories of Desire (2000)

Savage Love (2013)

The Mad River (1981) contains in a sleek 110 pages seven stories. I will mention two, starting with the last one first. In "Panther," Glover projects the voice of a 16-year-old forest princess in the first century AD, remote Europe. The Panther of the title is Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera (c. 22 BC – AD 40), whom Wikipedia tell us "was a Roman-Phoenician soldier born in Sidon, whose tombstone was found by railworkers in Bingerbrück, Germany, in 1859." He's also sometimes known as the father of Jesus. Yes, that Jesus. In 1981, when The Mad River was published, Wikipedia was not even a twinkle in anyone's eye; now it allows us to cut to the chase. The narrator of "Panther" is brought to the Roman military camp, abused, and chained. Two visitors arrive, one calling himself a physician. He heals the narrator, who overhears him later confront Panther about his paternity. I'm not going to spoil it any more than that. What I will say is that here is a story, based in history, driven by a powerful voice, a character caught in a violent, chaotic world, offering a view of resolution or escape, that ends with a sense of revelation or it is story? Yes, it opens outward to mystery. Gloveresque early defined.

The title story of The Mad River, which begins the collection, told in the third-person, places its protagonist, Hunter, in a kayak on a seething river. the reader is left to consider the metaphoric possibilities:

Hunter sculls tentatively at the bring of the chute, scanning for order in the spume-white chaos below. Like an artist he is an observer of line and mass. He watches the river bulge and rush, eddy and whirl, angrily blunt itself against the rock and then sheer off to be lost in the calm lower basin. He searches the river for meaning, ponders its ageless ambiguity. In an instant this river will compose his fate, all mutability and flux. Silently, he selects a course, signs to the others and gathers himself for the descent.

The next two lines are: "Consciousness funnels and intensifies the flow of experience. Time stops and does not stop."

Hunter looks ahead, seeking to chart a course through the seething river, as we seek to chart our courses through our days, some equally seething. What is real, and what are the distortions on our minds? The constant swirl makes it impossible to tell. Hold onto a moment, stop time, even as time continues. Glover is perhaps never more direct than here in laying out his perspective: the seer and the seen are one, or at least integrated and inseparable. Experience is trill, danger, often out of control, defying definition, and all we have. Interpretation, telling stories, is key. I don't want to be too theoretical here. The story is also adventure-filled, adrenaline-rushed.

The first thing readers will notice about Dog Attempts to Drown Man in Saskatoon (1985), apart from the delightful headline-ish title, is the cover, laid out like a newspaper with the story titles as headlines and the stories laid out like news.

Glover is a former newspaperman, so the joke is well held. It also begs the question about the relationship between the real and the fictive. New stories are stories; short stories are stories. What's the difference? Journalism is reported, and fiction is made-up. But see "The Mad River" above: "Consciousness funnels and intensifies the flow of experience. Time stops and does not stop." Language both represents reality and creates it.

The title story indeed includes a dog who in a way attempt to drown a man in Saskatoon. I like this story in part because it reminds me of the years I spent in Saskatoon (1992-94, see here and here). The South Saskatchewan River is strong in my memory. It isn't a river one wants a dog to drag you to in winter. I remember the Mendel Art Gallery, too, which makes an appearance. Mostly, I like the opening sentence, which gets us off and running, never to look back: "My wife and I decide to separate, and then suddenly we are almost happy together." This is another Gloveresque element: stellar opening sentences. Like this one, they often go in two directions at once, and then the story works toward a resolution — or widening the difference beyond repair. The narrator of this story struggles. The second paragraph begins: "Note. Already this is not the story I wanted to tell. That is buried, gone, lost — its action fragmented and distorted by inexact recollection." The certainty of reportage, this is not. The uncertainty of art, this is. It opens outward to mystery.

Turning quickly now to A Guide to Animal Behaviour (1991), which opens with the story, "Story Carved in Stone." It features another great beginning:

I thought my wife had left me, but she is back. What she has been doing the last two years, I have no idea. She's thinner. She has a Princess Di haircut, and she's wearing tight, three-quarter-length, white sweatpants and a black blouse. She's sitting across from me at the kitchen table, looking self-possessed and aloof. Her name is Glenna. She won't speak to me.

Ooof. Then we learn in paragraph two: "Brent Wardlow down the street had his wife leave five years ago. When she came back six months later, driving a new Eldorado with fluffy dice dangling from the rearview mirror, Brent asked her one question, and she was gone again the next day."

I'm just going to leave the rest of that one for readers to discover on their own.

What interests me next is "Swain Corliss, Hero of Malcolm's Mills (Now Oakland, Ontario), November 6, 1814." "Story Carved in Stone," obviously, is a take on the contemporary absurd. "Swain Corliss" is another shot into history; this time the War of 1812: "I should say that we had about four hundred — the 1st and 2nd Norfolk Militia, some Oxfords and Lincolns, six instructors from the 41st Foot and some local farmers who had come up the day before for the society." Glover has written about this story on his Substack. As he writes there, it is "based on family stories and local Norfolk County history." In another online post, he notes: "The Battle of Malcolm’s Mills took place six miles up the road from the family farm."

I remember reading this story and thinking I'd never read anything like it. Not the action per se, the setting. Taking the local history, bringing it forward, placing it within the context of contemporary fiction. Historical fiction isn't something that generally interested me, but this popped off of the page. As I read more Glover, I would see him return again and again to the origin stories of this place, call it what you will, Canada, North America, Turtle Island, America. As a teenager, those stories had seemed ancient and removed, which of course they aren't. They repeat and repeat, as ignorant armies fight by night. Like the dog in Saskatoon, these stories are based in fact, include elements of reportage, but live as stories, settling curiosities and opening new ones.

A Guide to Animal Behaviour, which was nominated for the 1993 Governor General's Award, includes the story "What I Decide to Kill Myself and Other Jokes," which was anthologized in Best Canadian Stories (1988) — and also Best American Short Stories (1989).

Next is 16 Categories of Desire (2000), which is where I first encountered Glover's work. Perhaps it's a good place to start; seemed so for me. I saw him read from this collection at the Imperial Library Pub around the time it was launched (2000). He read the title story: "Mama say there ain't but one desire which is the desire for Our Lord pure and simple." I wrote a review of this book for The Danforth Review, recently collected here on this blog. No need to repeat what I said there, but I will highlight a couple of things of interest. First, my copy of the book includes two notes I scribbled there back in the day.

p.36 romantic trap

(also story #1 -- R. inheritance)

p.54 'in love with sad drama'

The "R.", I believe is short for capital-R Romantic. Pages 36 and 54 also have the corner folded back, though so do many 25 other pages. This book engaged me! I don't know why I highlighted those two particular pages, but graduate school notes of historical inheritance were surely swirling in my head.

Oh, hell. Here's a bit from the review:

The extent of Glover capital-R Romanticism —and the vein is deep — makes 16 Categories of Desire a collection with a potentially lasting impact. It is, for example, eminently teachable. It is veritably awash with essay questions.

Compare and contrast Glover's depiction of a released mental patient ("Bad News of the Heart") with the monster in Shelley's Frakenstein (or with Wordsworth's madmen, for that matter);

Why do Glover's characters repeatedly say things like: "My entire life has been a struggle to liberate myself from love" ("Lunar Sensitivities")?;

Compare the emotional lives of Glover's characters with the one Goethe provides for his Young Werter.

Contrast the post-French Revolution politics of early-19th century England with the disillusionment of Glover's PR hack made rich by stock market fraud ("The Indonesian Client").

I also reviewed Savage Love (2013), also collected recently here. The review begins like this:

Instability recurs throughout Douglas Glover’s new short story collection, Savage Love. As the title suggests, love (or at least desire) is the dominant theme, but it is a love so unstable, so rife with conflict, so twisted against itself, that it shakes the confidence of its moorings. This is not love patient and kind, nor slow to anger; it is not a love that leads to calm plains of the soul; it is not the kind of love that will help you achieve satori, young bodhisattva. It is the kind of love that Toni Morrison once described as “one of those deepdown, spooky loves that made him so sad and happy at the same time that he shot her just to keep the feeling going.”

Toni Morrison wrote that line at the opening of her novel, Jazz (1992).

Savage Love is the longest and the most complex of Glover's story collections. It includes 22 stories in 264 pages, some only paragraphs long, the longest, and to me the most memorable, "Tristiana," 40 pages. That story again takes us into the past. It begins with the sub-head: "1869, Lost River Range, Idaho Territory," and it's as dark as anything you'll read by Cormac McCarthy. While this is the story that stuck in my memory the most, it isn't what I consider representative of the Gloveresque. If there is humour here, it is black. We have gone from Dog Attempts to Drown Man to no holds barred quest for wilderness survival. Readers who prefer the former to the latter, therefore, will be glad to know the collection includes six stories grouped under the heading: The Comedies.

One of the Comedies is a seven-page spritely thing called "A Paranormal Romance," which begins like this:

I was supposed to meet Zoe for dinner at a chic Parisian restaurant she had discovered on the Internet, a crucial rendez vous during which I intended to propose marriage. But I was running late.

Complications ensue. First there is the lateness, then the heavy rain, then the unexpected pop into a bookshop, where a mysterious and extremely short store woman provides an ancient French book out of which falls a piece of paper with handwriting on it, in English. The hand writing quickly fades, but not before the narrator commits it to memory. The handwriting speaks of another rendez vous, this one at the train station, also at the hour the narrator is to meet Zoe. He heads to the train station, it's close, Zoe is always late anyways. A bit of time travel is involved here, or is it? An open mystery, for sure.

The novels:

Precious (1984, 2005)

The South Will Rise at Noon (1988, 2004)

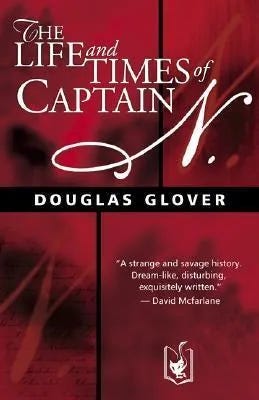

The Life and Times of Captain N. (1993, 2001)

Elle (2003)

I have reviewed the middle two on the list, reviews which can be found on the DC Collected page here, though the review of The South Will Rise is more impressionistic than summary. What it does summarize, is three of the four novels all at once:

If Elle is Glover's Rabelais novel, The South Will Rise At Noon is his Cervantes novel. Though if these broad generalizations mean anything at all, they only suggest that Glover draws inspiration from the broad tradition of the Renaissance humanists. Both Elle and The South Will Rise At Noon question how "story" (history) is constructed — as does Glover's other novel, The Life And Times of Captain N., which takes place at the time of the American Revolution and incorporates the perspectives of the Loyalists, the Revolutionaries, and the First Nations in a swirling tour de force.

I'll try to keep the novels grouped (and add in Precious), as I grapple towards some descriptive comments. Precious is a type of murder mystery, though its sleuth is a newsman, not a private eye or cop. The tone here mimics the hard-boiled, alienated, man-detached-from-society curios of the genre, to which Glover adds his distinct absurdist flair. Pynchon adapted the genre, too, as it enables the narrator to engage in interpretation and speculation and quest for meaning and disappear into mystery. What can be reported fact? What is story made up? How can we tell the difference? As I suggest above, these questions could be applied across all of Glover's novels, but that wouldn't tell you much about what they're about.

Having spent some time reflecting on what to say about these novels, I've decided I need to re-read all of them and write a separate piece, "On the Novels of Douglas Glover." All I can offer here is summary based on poor memory — and outside research.

Gooselane, publisher of Precious, offers the following:

The eponymous central character in Precious is a boozy, burned-out reporter with an embarrassing nickname and a penchant for getting into trouble. After three failed marriages and a humiliating stint in a Greek jail, he will do anything for the quiet life. A job as woman's page editor for the Ockenden Star-Leader seems like just the ticket — that is, until town gossip Rose Oxley winds up dead with a pair of scissors lodged in her chest.

Suddenly Precious finds himself embroiled in a hilariously over-the-top murder mystery, brimming with delicious satire about the newspaper business and culminating in a characteristically outrageous Gloverian showdown with firearms, snowmobiles, and booze. Inviting comparisons with the novels of Jasper Fforde and Ross MacDonald, Precious deftly combines an ingenious literary parody with the plot of a richly satisfying mystery.

Sounds carnivalesque, right? Now here's the Gloveresque (Gloverian?) opening sentence of The South Will Rise at Noon:

Looking back, I should have realized something was up as soon as I opened the bedroom door and found my wife asleep on top of the sheets with a strange man curled up like a foetus beside her. Right away I could see she was naked. ... I had not seen Lydia in five years.

Instability recurs. Quest for meaning persists. What is the plot? It has to do with the filmic re-creation of a famous U.S. Civil War battle, but mostly it has to do with the protagonist and narrator, Tully Stamper. The dust jacket bumf on my hard cover copy describes Stamper as "a modern-day knight errant and one of the world's last innocents," which is why I described The South Will Rise At Noon above as Glover's "Cervantes novel." And when we get to Glover's non-fiction below we'll see Glover has a lot to say, a book's worth, about Cervantes himself.

Regarding The Life and Times of Captain N., I've said elsewhere that it's my Canada Reads pick, the book I'd foist on every Canadian reader, at least once. What is the plot? I couldn't tell you, but the action takes place during the 1776 Revolution during which a father and son, separated sometimes, together sometimes, navigate competing views of the world: British Loyalists, American Revolutionaries, Indigenous communities. The father is a Loyalist. The son has an obsession with George Washington. The back cover of my 2001 Goose Lane Edition states: "The violent, erotic, and partly true story of The Life and Times of Captain N. trespasses into the psychic no-man's-land where the delirium of combat drives human nature into a primal frenzy."

Seeking commentary by others on this novel (the Goose Lane paperback begins with two pages of glowing quotations from 17 publications), I found Glover's own website list of critical bibliography, which included an essay in Philip Marchand's Ripostes (1998):

Douglas Glover's The Life and Times of Captain N. ... rewrites Walter D. Edmond's 1936 bestseller, Drums Along the Mohawk. That novel, which lives on in the form of late-night television broadcasts of John Ford's film adaptation, depicted stalwart American pioneers in upstate New York being terrorized by Indian and Loyalist raids during the American Revolution.

The 2015 reprint edition of the Edmond book includes a foreword by Diana Gabaldon with a broader summary:

When newlyweds Gilbert and Lana Martin settle in the Mohawk Valley in 1776, they work tirelessly against the elements to build a new life. As they clear land and till soil to establish their farm, the shots of the Revolutionary War at Lexington and Concord become a rallying cry for both the loyalists and the patriots. Soon, Gil and Lana see their neighbors choose sides against one another — as British and Iroquois forces storm the valley, targeting anyone who supports the revolution.

Drums Along the Mohawk was a bestseller when it came out, second only to Gone with the Wind (1936), apparently. Glover's version, however, is more existential than sentimental. As Marchand notes:

His characters experience such wistful uncertainty about the nature of things, mixed with a well-grounded fear that the world means them no good, that the reader suspects they have been reading Sartre and Wittgentein. And yet — such is the magic of Glover's historical imagination — they also seem completely at home in the seventeenth or eighteenth century.

I argue that the inverse is also true. As contemporary readers, Glover makes the eighteenth century as present as the latest Trumpist broadside. The identity conflicts of the Niagara frontier have bounced around the language for decades into centuries and zip across our consciousness today as vital as ever.

In Elle (2003), Glover takes readers deeper into the past, while also reminding us to confront our present, with its echoes of the past and eternal (or at least ever-present) human conundrums. Also based on a true story, Elle tells the story of a young French woman marooned on an island in the St. Lawrence River during Jacques Cartier's third and final attempt to colonize Canada (1541-42). For Elle, Glover won the 2003 Governor-General's Award for Fiction. What I remember most about it are the tennis balls and the bear — and the late appearance by Rabelais himself.

The non-fiction books:

Notes Home from a Prodigal Son (1999)

The Enamoured Knight (2004)

Attack of the Copula Spiders (2012)

The Erotics of Restraint: Essays on Literary Form (2019)

There is also a collection of essays about Glover's work:

The Art of Desire: The Fiction of Douglas Glover, Edited by Bruce Stone, Contributors: Bruce Stone, Louis I. MacKendrick, Claire Wilkshire, Lawrence Mathews, Phil Tabokow, Don Sparling, Philip Marchand, Stephen Henighan, Interview with Douglas Glover by Bruce Stone (2004)

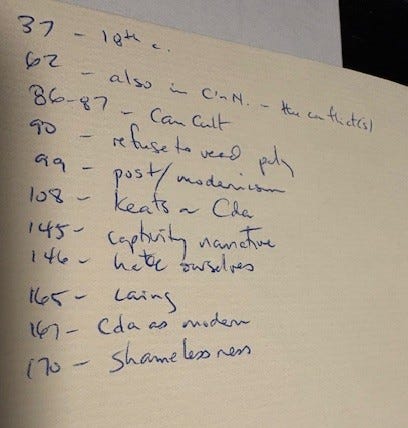

I have not picked up Notes Home from a Prodigal Son in over 20 years, but I cracked it open in preparation for this piece and my blood is tingling. I have noted elsewhere that when I read Notes Home, I discovered what I was looking for, the destination I was looking for. Glover had mapped the path, stuck his flag in the soil, and the fog lifted. He wrote about the writing life, the writing task, the writing, in ways that made intuitive sense to me. On the last page of the book, I jotted down notes and page number references.

Where to begin? Keats on Canada, page 108, jumped out at me. Keats? Canada?

And then there are a few Canadians who have what I think Keats meant by Negative Culpability, who don't mind being on the cusp, and who find the rhetorical position of marginality intellectually and artistically invigorating. Arcand is one. Hubert Aquin was one. The Leonard Cohen who wrote Beautiful Losers was another. Maybe the Margaret Atwood of Surfacing. Maybe Michael Ondaatje. There are others.

What about "refuse to read," page 90. Is that "poetry"? An ambiguous scribble. Not poetry, though.

The illusion of homologous goals happens when people lose their sense of irony, their sense of the ambiguous or polysemous nature of language, when they refuse to critique a discourse, when they, in effect, decide not to readd the whole message.

When we get to The Enamoured Knight (2004), this "not reading" critique expands. There Glover says, "If you want to read the book, you have to read the book." Seems reasonable, by why, then, are we in a sea of mis-readings?

Canada as modern, page 167, may be an insight revigorated by current circumstances (e.g., renewed threats of annexation).

...the position of the victim, the marginal and irrelevant — Canadians — suddenly becomes artistically and intellectually invigorating. It also just happens to coincide with one of the classic rhetorical stances of high modernism, the stance of the failed poet, the writer who cannot write, the stance of a Samuel Beckett, say, or Franz Kafka or Christina Wolf or Thomas Bernard or Milan Kundera, writers who see both the comic and tragic possibilities of marginality, and who see marginality as a metaphor for the self in the modern age — that self which everywhere feels somehow exterior and irrelevant to its own destiny.

On page 145/6 is a two-for-one: "captivity narrative" and "hate ourselves." This quotation comes from a 1984 interview with DG by Stanley Péan titled "The Sparks That Fly Off When Two Skins Touch." Actually, it is "adapted from notes for a live interview in 1984 in response to questions supplied in advance." That is, it was updated, post-1984, which is how it can reference a novel published in 1993.

One sure way to make yourself feel inauthentic is to tell yourself that everything you have done in the past, every memory you have, your whole history, is wrong. Thus in my work, I try to reflate the romance of the noble savage, which is at base an image of the human capacity to fall in love, to allow oneself to be recreated by the Other. Of course, the Other may have a difficult time surviving the operation — sometimes when you are redeemed, you die. And I have tried to reinvent (especially in my novel The Life and Times of Captain N.) the captivity narrative which may be North America's one true literary innovation. These efforts are meant to reposition the narrative of my/our selfhood, to remove it from its roots in Old Europe and also to extricate it from the post-revolutionary liberal reaction which is threatening to make us hate ourselves a second time.

There's a lot going on there, and in the margin I wrote "?". This interview is now over 40 years old, yet considerations of self/Other are as fresh as ever, though the framing and positioning today is often different. The notion of "reflating the noble savage" is riskier today without qualification. And who is that "us" in the final sentence? Notions of collective identity have exploded into infinite fractals in recent decades, perhaps especially since 2016. But when I look to the core of this message, the quest for and defense of authenticity, the spark of insight that comes from the confrontation with the Other, the acknowledgement of risk in that confrontation, and also the risk in not having that confrontation, I see and mind and heart working at the highest levels. And a writer explicating his craft and purpose. How to escape the past (Old Europe) and be real in the now — and the here, the specificity of place. It is not written this way, but this passage is a kind of land acknowledgement. To be here is to participate in the stories of this land, to be, in effect, captured by them, transformed by them, if you dare to actually engage with them, and to attempt to articulate that transformation.

If you want to read, you have to read. Enter the mystery, let it open you to the unknown.

Which turns us now to The Enamoured Knight (2004). Enamoured = lovelorn, questing for completion. This is DG's book-length essay on Cervantes's Don Quixote, published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615. I wrote a review of The Enamoured Knight for The Danforth Review, which is included on this blog's DG Collected page. Here's an excerpt:

In The Enamoured Knight, Glover returns again and again to critics who look into Don Quixote and see a world of either/or and argues theirs is a view too simple to be credible. To some, Quixote, the mad knight, represents the danger of the dream world, while his trusty friend Sancho represents the sane simplicity of the solid (real) everyday world of facts and mortgages. Glover shows the irony of that position: "If you want to read the book, you have to read the book." The words (facts) between the first page and last page of Don Quixote reveal a far more complicated world than the sentimental critics would have us believe.

I did not read The Enamoured Knight with a pen at hand. There is not list on the back page of favoured quotations, though some pages are dog-eared. Why? Who knows? But this is the start of the page on the first dog-eared marker, page 69. It shows both DG's challenge to the reader and his generosity to the author.

It may seem tedious to spend so much time on structural issues, on plot and subplot patterns, and the interplay of narrators, texts, irony, humour and language. But we do honour to the writer to try to have in mind as much of his novel as possible before making any deductions or leaping to any conclusions about it. It's important to spend time looking steadily at just what the author did on the page because it's always the case with an author as wonderful as Cervantes that the closer we look, the better we read, the more complex, subtle and interesting the book becomes. And it is the nature of a novel like Don Quixote, because of its proliferation of layers, parallels and reflective structures, that any one element is repeated, balanced, undercut, ironized, deformed or denied somewhere else in the book. It becomes less and less probable that any statement in the book can be taken to mean what it says it means, that the book itself is univocal. We need always to remember this. You can't read the book without reading the book.

It is useful to point out here that we have DG telling us how to read DG.

The concern with structure in fiction is a great transition to DG's Attack of the Copula Spiders (2012). Subtitle: "And other essays on writing." I'm going to focus on the essay/chapter, "How to Write a Short Story," first published in The New Quarterly, No. 87 (2003), which is where I encountered it first. In 2005, I quoted from it in "Short Story Theory" (lichen, no 7.2, Fall/Winter 2005), later posted here. What I quoted was this:

Consider, for example, two possible definitions of the short story by Douglas Glover (The New Quarterly, #87, Summer 2003):

A short story is a narrative involving a conflict between two poles (A vs. B). This conflict needs to develop through a series of actions in which A and B get together again and again and again (three is a good number to start with, but there can be more). Or, another definition I use: By a story I mean a narrative that extends through a set of articulations, events or event sequences, in which the central conflict is embodied once, and again, and again (three is the critical number here – looking back at the structure of folk tales) such that in these successive revisitings we are drawn deeper into the soul or moral structure of the story.

If you are inclined to theorems, Glover provides this mathematical-type paraphrase of his primary definition of a short story:

((GOAL=DESIRE)+CONFLICT+(SERIES OF INSTANCES OF CONFLICT=BACKBONE=PLOT))=(STRUCTURE=FORM).

I was also thrilled to discover DG's "Theory of Globs," which describes something I do in my writing — that I had no name for. For example, my story "27 Days" appeared in The New Quarterly (Winter 2012). TNQ asked me to write a reflection on the story, which was published at the same time — and later copied online here. The relevance of "globs" is, TNQ asked for a re-write because they didn't like the ending. The problem was, it had taken me years to find the ending. I wasn't going to change the ending. But I found a way to reorganize the "globs" in the story, so the reader's experience, the path that led to the ending, felt better. The story, in other words, was made up of chunks, what DG calls "globs," which can be anything, structurally (dialogue, description, exposition). Each glob, in my mind, is a unit of meaning; the math all adds up to the same conclusion, but the reader experience can be modulated in different ways. During the writing process, the writer may plot out the story in a linear fashion, then later realize (once the destination is clearer) that there is a more interesting way to reach the end.

And the end is what we are coming to.

DG's remaining nonfiction title is The Erotics of Restraint: Essays on Literary Form (2019). I haven't read it yet. I look forward to it.

I responded to Bruce Stone's The Art of Desire: The Fiction of Douglas Glover (2004) in another place, reproduced on the DG Collected page.

Keep reading the books!