Louise B. Halfe - Sky Dancer (1994)

In which the author moves to Saskatoon and removes the Last Spike

Lead with ignorance, your own: that's how I entered Saskatchewan in October 1992. I knew I couldn't go around introducing myself as "Michael from Toronto" without demonstrating significant humility. "You folks down east think you know everything!" I didn't want to hear that, so I led with the truth: I knew nothing.

I took the train from Toronto to Saskatoon (Treaty 6 & Métis Homeland). I could have flown, but the train seemed more interesting. It was. One never really gets a sense of how large Ontario is until one tries to leave it via land route. I had travelled the land route once before, in 1981, when our family had driven across continent for that year's big vacation. The train route, though, went further north, further remote. I remember what everyone remembers from these trips: rocks, trees, lakes. Miles and miles of them. But I also remember the train stopping in the deep north and viewing a scene out of the last century. This is the land where hunting and trapping were still a thing. This is the Anishinaabe homeland, though I wouldn't have called it that then.

I say "a scene out of the last century," but what did I actually see? The image of the memory is faint, the sensation of the memory stronger. But what of the image? I remember Indigenous men, dressed in a way that made me think they were trappers. What does that even mean? I remember the assumption I made, but I can't describe more than that. I grew up in Toronto (as noted above). I am of the first generation of Much Music. My mind was hot with the theories of Marshall McLuhan. Electronic media had changed the world. But here was a place that time had forgot.

Of course, that's not true. The colonial mechanism had reached even there long before. I was riding on a train track, was I not? Harold Innis, a forerunner of McLuhan, had described in The Fur Trade in Canada (1930) networks of communication across the continent. It didn't take electronic communication to make remote places not quite so remote. Electronic communication just sped up and radically shortened the psychic distances. I'd watched Pierre Burton's The Last Spike (1971) on TV as a child, and I knew the role the railroad played in "opening up the country," but did I really know what that meant? No, I knew nothing. In the fall of 1992, I'd just completed by BA, and yet I was ignorant. Ready for a new kind of schooling.

I arrived in Saskatoon 24-hours ahead of schedule, because apparently I couldn't read a timetable. The people who were going to meet me at the station weren't there, because they were home in bed. It was something like 5:00 in the morning. For some reason I took a cab—or got a ride—downtown to the bus station, or maybe just to downtown, where I tried to find an open coffee shop where I could wait until 9:00, when my ride would be at work. I had only his work number and a name, Tim. I had his last name, too, but right now I am smacking myself because I can't remember it. I called Tim and said, "Guess what? I'm here!"

"But you're not supposed to be here until tomorrow..."

"I know, crazy right? Apparently Canada is 24-hours smaller than I thought."

He came to get me and took me home to his family. He'd arranged a bachelor apartment for me downtown, furnished with used odds and ends, the basics, even a TV with banana ears.

I was in town on a two-year contract with the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) to work for Saskatoon Community Mediation Services as a Community Development Worker. MCC would provide me with the necessities of life at a subsistence level, and I would give my labour to this non-profit agency providing conflict resolution services to the justice system and community. The connection to Mennonites is those two words: conflict resolution. Or to use another terminology, the ministry of reconciliation (2 Corinthians 5:11-21). (Interesting how even Bible quotations have online advertising...)

What this meant in practice was, the agency had a contract with the provincial government to manage the diversion of first-time shoplifting offenders out of the court system. I'm going to say straight up that this is a good thing, and also that this had nothing to do with mediation. Mediation is a negotiation between two or more parties, working towards a mutually acceptable solution. Diversion is a way for the government to reduce court costs, allow the offender to exit the process without a criminal record, and enable the store (usually via a security officer who attended the meeting) to receive a written apology from the offender. I say "offender" in this case, because the person was required to plead guilty (accept responsibility), so they were no longer "the accused." The process was mutually agreeable, in the sense that all parties got something they wanted, but it wasn't a negotiation. Every meeting followed a template. All that deviated were the offenders' stories.

The diversion program was premised (beyond the cost savings to government) on the fact that most adult first-time shoplifting offenders were anomalies. That is, they weren't stealing so much (though they were) as they were "acting out" some crisis in their lives. Marilyn Lastman, the now late-wife of now late Toronto Mayor Mel Lastman, is one prominent example. Adult shoplifters turn to theft in response to stress, in a kind of call for help. Mrs. Lastman had a lot of stress in her life. Winona Ryder is another prominent example.

The diversion contract with the government kept the lights on at the agency, as it tried to build up other programs with more active conflict resolution / mediation activities. When I arrived, the agency had an executive director, C-, an administrative assistant, VF, and one other staff person, our "mediator," MF. The agency was offering "community mediation," a service to anyone in town who had a conflict and wanted to engage with the person(s) they were in conflict with with the help of a third-party. I believe this option was available generally to the community, but the agency was also trying to have the justice system refer applicable civil-related conflict-based cases to the agency. Conflicts between neighbours, for example, that had escalated to the point of entering the court system.

The agency also had a program in local schools training "peer mediators" in grade five classrooms. In fact, this was the agency's most "on point" program. Grade five students were trained as conflict mediators, given identification as such, and sent into the schoolyear at recess and other common times during the day, to be available to students who needed help sorting whatever out. The training taught the students the difference between positions and interests, assuring them that positions may differ, but usually people share a healthy degree of common interests, if you can help them identify them. We used the story of siblings fighting over an orange. Each wanted it. The parent said, "Fine. I will cut it in half." But one wanted the rind to make marmalade, and the other wanted the fruit to eat. Each could have gotten 100% of what they wanted, if the parent had helped them move from position to interests.

Of course, before I could help the grade five students learn this, I had to learn this myself. The concept of "interest-based negotiation" was new to me. What's certain, is that it has never left me. One of the most important things I've ever learned, I learned in Saskatoon: The best non-negotiated option needs to be worse than the best negotiated solution. Otherwise known as the Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement. Upon arrival in Saskatoon, I was handed Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (1981), by Roger Fisher, William Ury, Bruce Patton. Here was a life skill that I had, until then, sorely missed. Never even anticipated.

The schools where the agency taught conflict resolution to the 11-and-under set were in the Saskatoon "inner city." I will admit that at first I forgot to lead with ignorance. Inner city? Saskatoon? I mean, I'm from ... if I haven't told you already ... TORONTO ... where we have INNER-CITIES. But the cliche proved true, pride fell before the fall. I knew nothing. I realllly knew nothing. I remember our agency admin telling me, "Don't go up 20th Street." Again, I was like - I've wandered through Kensington Market at 1:00 in the morning, but okay, sure.

The biggest fact of my ignorance was that I didn't expect Saskatoon to be a racially polarized city, but within weeks of arrival I knew this polarization to be the number one fact of civic life. The so-called inner-city consisted of almost entirely Indigenous people, mostly Cree, with connections to reserves across Saskatchewan and the prairies, and it was the worst housing stock in the city, with the highest unemployment, highest violence, and also public schools full of mostly Indigenous kids. My agency colleagues recruited me to assist with the training. We had little booklets and acted out little scenarios as part of the training, which got me into the school, which I will never forget.

First, that was 30 years ago, so those 10-year-old kids would now be 40. Strange to think. Second, I'm not Indigenous, our trainers were not Indigenous, the teachers in the school were not Indigenous. Yet, the school itself was plastered with posters about Indigenous culture and positive self-esteem. The school staff were very aware of who their students were, the challenges they faced at home, and the hope and ambition they wanted to instill in their students. I'd never seen anything like it. I shook my head at my Toronto pride and felt humbled. The local newspaper ran stories of murders in the area, of extremely young prostitutes picked up on freezing street corners. There was a world here I knew nothing about—despite my faux world-weariness—and I promised to do my best to keep my eyes open.

Our agency was expanding and one job they gave me was to put together a training manual, so they could run mediation training for adults. I pulled together a selection of resources from different sources, and we ran an ad in the local newspaper for trainees. More than we could handle applied. We also offered spots to two Indigenous women from the inner-city, because we were self-conscious about our agency being very white, and we wanted to build relationships with the local Indigenous community. Out of that training, we would soon hire our second mediator, KM. The two Indigenous women didn't complete the training, and I think about that still. Was it us? Was it other circumstances? Could we have been more inclusive or accommodating? Was it just what it was?

I didn't understand the Indigenous - non-Indigenous dynamics of the city, but I could see that it was changing. People told me so, directly. Indigenous people were talking about their culture more publicly than they had before. There was an event at the Broadway Theatre, where folks took the stage in their regalia and explained what different elements meant, what the songs meant, what the dances meant. To me, it felt natural, very Toronto, almost. My public school had students from 75 ethnic backgrounds. Everyone had stories, different ways of doing things. We talked about it. Sometimes we mixed and matched, projected ourselves into different roles. It seemed second nature. But I was told that this Broadway Theatre event had never happened before. The information being shared was often held private. I kept my mouth shut and said, "Thank you. I'm grateful to know more."

Our agency shared space with the John Howard Society, the prison-rights advocacy and service agency. One day I came into the office and went to my desk as usual, but quickly it became clear that others in the office were not acting as usual.

"What's going on?"

"David Milgaard's in the front room. John Howard is trying arrange some things for him."

I peaked around the edge of my cubicle, but I was yanked back.

"Don't look."

But I had seen him. He looked like the most broken man I had ever seen, something I will never forget.

From Wikipedia (accessed June 25, 2022):

David Milgaard (July 7, 1952 – May 15, 2022) was a Canadian man who was wrongfully convicted for the 1969 rape and murder of nursing student Gail Miller in Saskatoon and imprisoned for 23 years. He was eventually released and exonerated.

He was 17 years old when he was sentenced to prison. What I remember from that day was how everyone was on high alert. Milgaard sat in the waiting room and was then led to an inner office, people scrambling to arrange what he needed.

DNA analysis in 1997 would prove that he wasn't the murderer, but when I saw him in Saskatoon he had been released from prison but not exonerated.

He was man more stuck, most lost, than anyone else I have ever seen.

The Tragically Hip would write a song, dedicated to him, "Wheat Kings" (1992).

One of my colleagues at the John Howard Society was a Cree woman whose name I can't remember. I was about 25 then, and she was about 40, and I thought she was maybe the most beautiful woman I'd ever seen. She later died of breast cancer. At the John Howard Society, she ran an addictions program, and often I would come into the office and the white board would be covered with her notes from her session the night before. Frequently, the board notations on the board included a circle divided into quadrants. One day the circle and quadrants were interrupted by a swirling line that led to the centre of the circle where there was written the word, WILL.

"What's this about?" I asked her.

"That's the medicine wheel," she said.

"The what?"

"It represents the points of the compass, the four seasons, and many other things."

She explained she used it as the basis for her addictions sessions. For the person, the four points of health were—physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual.

"What's the swirling line going to the word WILL?"

"We want our folks to think about health as balancing and integrating the four points of the compass. It's not going in towards WILL. Will is the beginning. You have to use your will to make choices about where you are and where your going, being aware of where you are at in the wheel."

"Oh, wow."

Since that day, I've often thought about the medicine wheel and asked myself if I'm in balance or not. Usually, if I have to ask myself that question, I'm not.

Medicine wheels were not just circles on the white board, though. It's not just a concept, they are literal things, rings of stones on the prairie, placed there since time immemorial—long before the arrival of the train, in other words.

Going to take a short detour here to say Saskatoon is so far north, you can often see the northern lights, another mystic. I once saw the northern lights in Ottawa, which was amazing and kind of freaky: "Like crystal!" I've never seen the northern lights in Toronto, but my Dodgrib pal RVC says you can call them by rubbing your finger nails together. Try it, folks. I do. I try, try, try. I keep trying.

Many medicine wheels across the prairies have been removed to facilitate agriculture, but not all of them. There's (at least) one at the Wanuskewin Heritage Park outside Saskatoon. Wanuskewin began to feel a bit like a home away from home during my time in Saskatchewan. I visited many times. I don't know if they still have the same audio-visual display/story, but I will never forget the haunting question it asked: "What does Wanuskewin mean TO YOU?"

I saw a pair of Great Horned Owls there once and many hoop dancers, fancy dancers, singers, and drummers. What does Wanuskewin mean to me? It seemed home to the invitation to learn, to remember, to contemplate, to be the genesis to a reconciled future. Will pushing the swirl through the four points of the compass to balance.

Well, that was 30 years ago, and whatever optimism I back then, it has tempered significantly. I know from being around justice system-type folks back in those days, that everyone was well aware that Indigenous people were grotesquely over-represented in the prisons, in the court system, in the police records. There were plans to address that. I thought, then, things are on the path to a correction. Nope. If anything, the pattern is more entrenched than ever.

From the Saskatoon Star Phoenix, February 9, 2022:

In December, federal Correctional Investigator Ivan Zinger released new information that showed Indigenous women account for 50 per cent of all federally sentenced women.

In January 2020, Zinger reported that overall, Indigenous peoples comprised 30 per cent of all federally sentenced inmates.

Provincially, Indigenous overrepresentation in the jail system is even greater — about 75 per cent of adults in Saskatchewan’s jails. That ratio has been consistent for about the last five years, according to Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Corrections, Policing and Public Safety.

The ministry provided a single-day snapshot of the inmate population dated Dec. 15, 2021. On that day, 77 per cent of adults in custody were Indigenous, 21 per cent were non-Indigenous and three per cent were of unknown race or didn’t self-identify (emphasis added).

The 2016 census indicated 16.3% of Saskatchewan’s population was Indigenous.

*

I asked my step-children, who are +/- 20 years old, what they know about Saskatoon, and the first words out of their mouth were the same: starlight tours. These events are taught in Toronto high schools.

From Wikipedia (accessed June 25, 2022):

The Saskatoon freezing deaths were a series of deaths of Indigenous Canadians in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in the early 2000s, which were confirmed to have been caused by members of the Saskatoon Police Service. The police officers would arrest Indigenous people, usually men, for alleged drunkenness and/or disorderly behaviour, sometimes for reasons without cause. The officers would then drive them to the outskirts of the city at night in the winter, and abandon them, leaving them stranded in sub-zero temperatures.

The practice was known as taking Indigenous people for "starlight tours" and dates back to 1976. As of 2021, despite convictions for related offences, no Saskatoon police officer has been convicted specifically for having caused freezing deaths.

When I returned to Ontario in 1994, I was alert to what I'll simply call Indigenous issues in a way I had never been before, even though I'd long considered myself alert and aware. But it was in Saskatoon that I saw Alanis Obomsawin's movie, Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance. It played at the National Film Board cinema in town, and I saw it there twice, riveted.

Back in Ontario in 1994, whatever Indigenous culture awakening was breaking through to the public consciousness in Saskatchewan wasn't happening "down east." That didn't come until many years later, and sadly it wasn't after the 1995 death of Dudley George at Ipperwash. The 2007 report of the Ipperwash Inquiry was a landmark document, and the historical reports produced for the report *** and available online *** lay down a remarkable historical record, but it wasn't until around the time of the 2015 final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, that the public awakening started to break through. For many, though, it took the 2020 "discovery" (long known by many) of unmarked graves at the sites of former residential schools across the country. I'm glad to see impatience with progress among young people now. I'm impatient as well. I have seen many markers of progress, but also I thought for sure 30 years after I started my time in Saskatchewan that we would have at least both feet out of the starting gate.

*

If you are still here, then surely you are wondering: When are we going to get to Sky Dancer?

The most beautiful woman in the world.

That was how she was introduced when I saw her for the second time, which was at the Toronto Reference Library on October 13, 2017. My blurry photo of Lee Maracle, Louise Bernice Halfe, and Maria Campbell below.

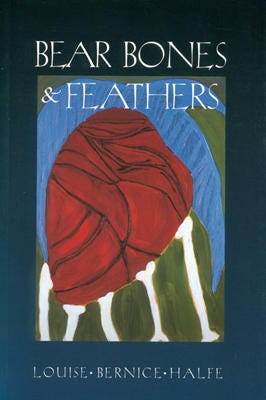

The first time I saw the future Poet Laureate of Canada was in 1994, shortly after the release of her first book, Bear Bones & Feathers (Coteau Books, 1994), recently re-released by Brick Books (2022). I don't remember the location. It might have been the Friendship Centre. I remember she was there with her husband. She was humble, quiet, shy, anxious, maybe, but also fearless, tough, and so, so good.

Immediately, I thought: "This is terrific. This is immeasurable. This is the real deal."

Later, dear reader, I bought the book. I watched from afar. Heard of her from time to time. I have never been less surprised of anyone’s rise to prominence and never more pleased.

I think of myself now on that train headed for Saskatoon and seeing what I perceived to be trappers and having no context to understand what I was seeing. I feel slightly more capable of understanding that context now, but as with many things—the more I learn about this country, the less I know. The Canada of The Last Spike, the Canada of my childhood, is gone. Never existed, I know, but did exist in my imagination and the imagination of many others. It is gone from my imagination, now. So, at least there's that. Skydancer, and many others, have helped me to fill in parts of the gap, but they've also shown how large a gap it actually is. Thank you. Miigwetch.

It's taken 30 years to come not very far. If I get another 30, I plan to go at least a little farther.

This is the first of what may turn out to be three posts on my Saskatoon years.

Brilliant. Me? 1979, Saskatoon. Dark evenings on 20th Street, white boys screaming insults at native women, even girls, as they roared by in pickups. A bar on 20th Street where I watched seedy, overweight white men squiring stuperous, self-anesthetized, much younger native women. Worst overt racism I have ever seen. Such a good post, Michael.