Mo Yan (2000)

In which the author works, gets fired, writes, publishes, doesn't publish, keeps going anyway, the 21st century begins, a pie gets made

Ah, the year 2000. It was strange, wasn't it? To go from saying nineteen-ninety-nine to The Year Two Thousand. Seemed like going from lower case to Upper Case. For me, it meant the temporary job I had at the Government of Ontario, working on a Y2K project, came to an end. But it also meant, the contract writing job in the Information Technology Services Branch was finally a possibility. It had first been dangled in front of me eight months earlier. Now it was here. In January 2000, I signed a six-month fee-for-service contract to be a writer in the IT department, working as part of a small team on an Intranet. Not a spelling mistake. Not the Internet; an Intranet.

This was, suddenly, by far the most lucrative job I'd ever had — paid $1,000 a week and that came to me direct, no deductions. The project manager was also an independent contractor, and he was super charismatic. He had lots of ideas about how he wanted to do this thing. An Intranet was a communication tool, sure, but more importantly it was a hub for workplace processes. We just had to corral all of the different areas to get them to agree on some standards and shared accountabilities. Those of you who are laughing already, yes, you, you know the score. The real job was the corralling, which could only realistically be done by folks higher up the org chart. Also, communications branch was pretty sure the Intranet belonged to them, not the IT branch, so it wasn't going to play ball until it, well, got the ball.

Our little team was down the hall from the team that managed the Government of Ontario main page, which was coded HTML. If it had any interactivity, I don't remember it. One section "about Ontario" included a short history of the province that ended with Expo '67. Certainly, there was nothing after 1970, basically my whole life. At one point, I suggested we write something for the recent decades. I may even have started a draft, but nothing came of that. This was an episode that seemed symbolic of the state of Canlit, too. The cultural assumptions of the 60s & 70s persisted, but the ground had shifted, dramatically, and the speed of the change was about to radically accelerate. But so many seemed numb to it, as is ever thus, I guess.

Then the IT branch was blown up. All of the managers and directors had to compete for their jobs (again), and halfway through my six-month contract everybody I'd been reporting to had been replaced. Don't worry, we were told. If you're on a contract, we'll honour it. I was watching my savings pile up, and I thought: maybe I'll just self-finance a few months of writing? I signed up to attend the two-week Sage Hill summer writers' workshop and noted my time off on the workplace vacation schedule. The workplace had devolved into benign chaos, that is, my nominal manager wasn't paying me any attention, so I just left.

When I returned two weeks later, she told me I'd been fired. I couldn't just disappear. I walked her to the vacation schedule on the wall and showed her my time off had been recorded. She said, "It doesn't matter. Your two weeks notice started last week. We'll pay you until Friday, because you'll always do this."

I'll always do what? I wondered. Go on writing retreats? Take vacation?

In any case, I was gonski, and quickly two other opportunities opened up. Artscape was looking for Artists in Residence to live on Toronto Island for the month of September. I applied; I was accepted. Also, a member of the Writers' Union of Canada was looking for another writer to housesit his family place on Pender Island, B.C., for the winter. I wrote a compelling email and got that gig, too. Holy! Summer writers' workshop, month-long residence, winter house-sitting gig, pile of cash in the bank. Bring on the 21st century. Fire me from my lucrative IT job! What do I care?

A bit on Sagehill, where I was in a group with Richard Van Camp, Kate Sutherland, Nancy Richler, and Susan Ouriou, led by Bonnie Burnard, who had just won the Giller Prize for A Good House (1999). The group was for people who had published at least one book and who were looking for advice about how to extend or make next steps in their literary career. We were each also working on a manuscript, but we didn’t do a lot of workshopping that I remember. I often hung out with the poets, which is a lifelong habit. My manuscript was in a mess and consisted of experimental fragments. Burnard confessed she didn’t know what to do with me. I said, no problem. Me, neither. Just keep going, she said. Yes, I said. I intend to.

What can I tell you about Bonnie Burnard? She was a scotch drinker. Her ex-husband and a bison (?) ranch, which as a Toronto boy myself seemed otherworldly. She like Steve Earle, singer and story writer. Winning the Giller, which she hadn’t expected, brought in more money than she’d ever thought had been reasonably possible. She had a story about being groped by a well-known writer at a previous Sagehill retreat. Incidentally, Sagehill was held at a monastery in the Qu’Appelle Valley, and the monks were around. Someone else told me a story about a previous retreat: a participant had achieved intercourse with a monk while enabling him to also maintain his vow of silence. Nothing so interesting happened while I was there, as far as I know. We are all told to beware of ticks.

Throughout this period, I was publishing my nascent online literary magazine, The Danforth Review. In 2000, TDR published issues in March (#3) and September (#4). The September 2000 issue was the last issue that I hand-coded in HTML. Starting with the next issue (January 2001), the magazine started being a Frontpage web. This is a legacy of my IT job and the first project manager there, who had tried and failed to get the powers that be to make their Intranet a Frontpage web. Frontpage is/was a Microsoft website development program. It certainly simplified the website management and publishing process for me. That project manager also had his own site hosting company, so he assisted me with that, too.

These early versions of TDR are archived at the Library and Archives Canada. What I didn't know then was that TDR would become one of the biggest projects of my life, continuing until 2018 (with a break from 2009-2011). I was the publisher and fiction editor. The poetry editors were Geoff Cook and Shane Neilson. I met Geoff through his father, Greg, who'd been the writer in residence at the University of Waterloo circa early 1990s. Shane found TDR online and asked if he could be involved. I don't think I ever turned down a volunteer. The whole project was lightly planned and founded on experimental energy. We would go with the flow until it flowed no more, and it flowed for quite a while. From time to time, I was asked "what is your intention" with TDR. The intention was ill defined and minimal. To be a literary magazine. To experiment with the form of a literary magazine in a new medium, e.g., online. To offer a place to publish new poetry and fiction. To focus on the Canadian small press scene, offering reviews of new books and interviews with authors.

As fiction editor, what sorts of stories did I like to select? I've always found it hard to say. I found most submissions to be decent, even back at the beginning. Anyone who is going to go to the bother of submitting their work to a magazine knows what they are doing. So how does one story stand out over others? A unique scenario. A notable facility with language. A quirky sense of humour. Something intangible that makes it stand out as different from the others. Eventually, I worked out a system where I would accept submissions for a month, and I would receive roughly 200, then I would go through them and get it down to about a dozen, then I would try to curate a good mix of final selections, four to six, trying for a gender balance. A good mix? A selection of stories that seemed to fit well together.

I'm not going to do a full TDR analysis here. Perhaps another time. I will say that the first four issues were published like a journal, all content posted up at once. But after TDR became a Frontpage web, I started posting new content every week, which made it a website acting like a website. The form evolved as the technology evolved, though TDR never embraced the social media revolution. Somehow, that was a step too far. I wasn't interested in "content creation," I was interested in "literature online." I didn't care about attracting eyeballs and clicks. I wanted to nurture literary conversation, sometimes serious, sometimes irreverent, sometimes snarky, sure, but always self-deprecating, I hope. I wanted the online world to reflect back to the real world, though. To books. To writers. To creative ideas. To celebration of the life of the imagination. Art/Life. TDR was also a way for me to continue my literary education. It connected me to new books, new writers, new roles as editor/publisher/interviewer. For the next few years, two issues of new fiction/poetry appeared annually. The week-to-week focus was on new reviews/interviews.

In 1999 and 2000, I interviewed Hal Niedzviecki, rob McLennan, and Mark Anthony Jarman. Hal was the co-founder of Broken Pencil and had been, I think, involved with the lit mag Blood & Aphorisms, I believe. Perhaps not. In any case, I associated him with Ken Sparling, who was B&A editor and whose first novel, Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall (1996) was edited by Gordon Lish. rob was rob. He was then what he remains, an energy centre for small press publishing in Canada. MAJ I'd only recently become aware of. I reviewed for TDR an anthology that intrigued me from the title, Turn of the Story: Canadian Short Fiction on the Eve of the Millennium (House of Anansi Press, 1999). The anthology included "Burn Man on a Texas Porch," and to this day I can say this story shocked me awake greater than any other piece. Soon afterwards, I was give the opportunity by Quill & Quite to review MAJ's new collection, 19 Knives (Anansi, 2000), which I loved, so it was a no-brainer that I would reach out to see if MAJ would submit to an interview. One thing from that interview I've never forgotten is the image of MAJ reading John Cheever on a bus:

I also think of John Cheever as an invisible influence, in that people reading me wouldn't think of Cheever but he's a huge influence. I once rode a Greyhound from Philly to Seattle, three days on a bus and his collected stories kept me sane. It was also important for me when I started writing to find writers who wrote about where I lived (in the west). Until I read Robert Kroetsch's Studhorse Man or Ken Mitchell's short stories Everybody Gets Something Here, I thought you had to write about New York or Paris or a safari somewhere else, and not where I was from.

I travelled from Toronto to Saskatchewan and back by bus to get to Sagehill, including a side trip to Saskatoon to see friends and the Joni Mitchell painting exhibit and the Mendel Gallery, which I see was dissolved in 2015. Wow.

Later in the year, I took a bus from Toronto to Vancouver on my way to Pender Island.

Speaking of Art/Life, what was I working on at all of these writing workshops and retreats in 2000? Nothing that ever got published, and I've never done a writing retreat or week-long workshop or house-sitting since. This period was the most "writerly" period of my life, and it produced no work that lasted, except the collective online experiment that was TDR. Seems strange in retrospect.

My debut short story collection, Thirteen Shades of Black and White (Turnstone Press, 1999) had appeared the year before, and I had sought out reading opportunities and tried to meet people in the Toronto literacy scene. One hive of activity was the Toronto Small Press Fair, where I rented a table and stacked up my books. Optimistically, I brought 20, and I think I took all of them home again. One guy picked up a book, flipped through it, saw the Canada Council logo, and wanted to know how I got a grant. It's all a scam, isn't it, really? I said I hadn't got a grant. But the logo was there! The publisher got a grant. He put the book back on the pile and walked away.

The Fair was key on another level, though. It was there that I met Max Maccari and Nathaniel G. Moore. Max was starting a new publishing company, Boheme Press, and he was looking for manuscripts. He asked me if I had one. I said I had a novella I wrote as an undergraduate, which was pretty interesting, if I did say so myself. He said to send it to him. I did, and not long afterwards we signed a publishing contract. The novella and a handful of new stories. Nathaniel would become a deeply important partner in TDR in the years ahead. He was a few years younger than me, but also an East York kid with literary dreams, which have unfolded on their own unique paths. That's a tortured metaphor, I apologize. NGM would make TDR has much his as it ever was mine.

My Boheme Press book was Only A Lower Paradise (and Other Stories), and it appeared in fall 2000, after my time on Toronto Island and before I took off for Pender Island for the winter. It felt great to have another book come out so soon after my first one, and strangely it felt, um, natural. This is what life was going to be like, right? One year after another, one book after another. Absolutely not. In the years that followed, I would work and write, and write, and write better than ever I felt. I would collect the stories, which were getting published in magazines, and submit proposals to publishers. I have a collection of generous rejection letters, but acceptance remained elusive until rob mclennan agreed to publish The Lizard and Other Stories (Chaudiere, 2009), but that's a later story.

I connected Max with Matthew Firth and later, together, they put together the anthology on work and sex, Grunt & Groan (2002). For that anthology, I wrote "The Lizard," later the title story of the Chaudiere book.

Later Boheme went bankrupt. Maybe even by 2005. And Max disappeared. Quill & Quire reached out to me to see if I knew where he was. I didn't. Before he disappeared, though, he gave me boxes and boxes full of Only A Lower Paradise, 500+ copies of the book, which I kept until I moved in 2021, when I dumped most of them into the recycling blue bin outside my house. Once, when my neighbours organized a street sale, I set out some copies on a table, offering them for sale for $2 each, far below the cover price. No one bought one. One woman stopped, picked up a book, asked me if I was the author, heard me affirm, yes, I was, then put the book down and walked away.

The project I was trying to push forward in 2000 in the workshop, retreat, house-sitting period was a novel I once described as "about space aliens and the death of the family." It got written, consisting of 12 chapters. The family had a mom, dad, teen sister, and younger brother. The brother saw aliens and the rest of the family didn't believe him, but he really did. Each character had three chapters dedicated to them. Each character had his/her own story arc, but the younger brother's story linked all of them. It was always an easy plot to describe. Highly organized. Systematic. Ultimately, boring as hell — though good on a sentence-by-sentence level, I'm sure. Haha. Anyway, I saw that whole thing through, and I still have it. The title was Four Quarters Past Midnight.

In the middle of the table a large candle burned, sending smoke twisting up through the crystal chandelier overhead. Jeremy poked the candle with his fork, sending his utensil into the beast with a swift jab. Four puncture holes. Nothing emerged. He returned his attention to his spaghetti. His mother’s eyes turned towards him. That child, she thought. What a wild one. For over a month he had been warning them aliens were about to attack Earth. The aliens had spoken to him and given him an assignment. To be a lookout. To monitor his neighbourhood for unusual events. A creeping space menace had infected the planet and the aliens were after it, like surgeons after a cancer.

“My job is to record anything strange, because that’s evidence the poison from the space spores has started.”

On a personal level, I met an artist young woman on Toronto Island, and we became a pair. She would come to visit me on Pender Island, and we re-connected when I returned to Toronto in Spring 2001. More on that story later.

Other things happening in 2000? Well, Bush v. Gore, sure. I was living that in above the Sunset Grill on Danforth Avenue at Coxwell. In the summer, someone broke in through the front door and stole the laptop I had recently bought off my brother. I had intended to take it to the Saskatchewan workshop. I called the police, who sent someone to dust for fingerprints. Ultimately, he decided it wasn't worth it, though he would if I wanted to. It was more likely to make a major mess than to reveal any results. I said, Okay, forget it. As I walked the officer out, he saw that his unmarked police car was in the process of being ticketed for illegal parking. He flashed his badge, but the other officer just ripped the ticket off his pad and handed it to him.

I wrote the above summary of 2000, then I searched to see if I could find an archived version of my website — and a list of 2000 "events."

November 10, 2000. Black Sheep Books. Vancouver, B.C.

October 18, 2000. BOOK LAUNCH! Top o' the Senator. 269 Victoria St., 6:30 - 10:00, Toronto, Ont.

October 14, 2000. Spoke at Loyola High School, Montreal, Quebec.

October 2000. Story: "Watching the Lions." Another Toronto Quarterly.

October 2000. Review of Wolves Among Sheep in Quill & Quire.

October 10, 2000. Toronto Public Library panel, Writing on the Web.

October 1, 2000. Canzine. The Big Bop. Toronto. 1:00 pm

NEW BOOK! Only a Lower Paradise. September 2000.

Sept. 11 - Oct. 10, 2000. Writer-in-Residence. Toronto Island.

Sept. 10, 2000. Eden Mills Writers Festival. Eden Mills, Ont.

August 14, 2000. McNally Robinson Booksellers, Grant Park, Winnipeg, Manitoba: 7:30 pm.

August 2000. Review of Fighting for Canada: Seven Battles, 1758-1945 in Quill & Quire.

July 31 - August 10, 2000. Sage Hill Fiction Colloquium. Lumsden, Saskatchewan.

June 19, 2000. Canadian Booksellers Association Convention, Toronto.

May 21, 2000. Club Zone. Montreal.

May 14, 2000. Ottawa Small Press Fair. Glebe Community Centre. 690 Lyon (at Second). Noon-5pm.

May 7, 2000. Starbucks. 2253 Queen St. E. 7:00 p.m.

May 6, 2000. Toronto Small Press Fair. Trinity-St. Paul's Centre. 427 Bloor St. W. 11am-6pm.

Spring 2000. Short story: "Once Upon a Time" in Voices Under the Guise of Darkness Anthology, Buring Effigy Press & Productions

Spring 2000. Short story "This is My Place" in paperplates (pdf).

May 2000. Review of Mark Anthony Jarman's 19 Knives in Quill & Quire.

April 29, 2000. Starbucks. (Old Britnell's location. One block north of Yonge & Bloor.) Toronto. 2:00 p.m..

April 9, 2000. Starbucks. 2253 Queen St. E. Toronto. Speakeasy Cafe Reading Series.

April 2000. Review of Barbara Lambert's A Message for Mr. Lazarus in Quill & Quire.

March 27, 2000. Short story "Drew Barrymore's Breasts" published in Pro Tem (York University).

Winter 2000. Short story "12 Days of Unemployment" published in Geist No. 35.

February 2, 2000. Conrad Grebel College. University of Waterloo. Community Supper.

February 2000. Book review of Michael Holmes' Watermelon Row in Quill & Quire.

January 30, 2000. Starbucks. 2253 Queen St. East. Toronto. Speakeasy Cafe Reading Series. FREE.

January 26, 2000. Hart House, Writuals Series, University of Toronto. 7:30 p.m. FREE

January 16, 2000. Starbucks. 1984 Queen St. East. Toronto. Media launch of Speakeasy Cafe Reading Series.

January 14, 2000. I.V. Lounge Reading Series, 326 Dundas St. West, Toronto. 8:00 p.m. FREE.

January 2000. Book review of Mike Barnes' Aquarium in Quill & Quire.

Some stories of (perhaps) interest emerge from this list. I shared the reading at Black Sheep Books with Clark Blaise. I don't believe I knew who he was at the time. Black Sheep Books was a hole in the wall store, suitable for me, a tiny venue for Blaise, who was there with his wife, writer Bharati Mukherjee. They were both friendly to me. Blaise read from The Sorrow and the Terror: The Haunting Legacy of the Air India Tragedy (1987). I was humbled.

The April 29 reading at Starbucks/Britnell's was part of a day-long event. Multiple writers were booked. I had a time slot. No one seemed interested in me. Coming up soon after me was someone far more exciting, Evan Solomon, the TV personality who'd published a novel. I didn't stick around to see him. It was sad to see Britnell's book store turned into a Starbucks, but it's even more sad to see it now, a former Starbucks, now derelict. It was one of the oldest bookstores in Toronto and had frequented by Hemingway, reportedly, in the 1920s, when it had been TO's link to international modernism. Maybe it still is.

What strike me now about the list above is, what a lot of activities! Also, almost none of it generated revenue. Quill & Quire paid $100 for a review. Boheme gave me $300, I think, for the new book. None of the readings paid anything, and if I sold a book at any of the readings I'd be amazed to hear about it. I got a small cheque for the Toronto Public Library event, which was organized by Hal. It was a slim audience. I took one question: Did I know how to make money writing online? Clearly not.

***

I was thinking about writing about Mo Yan, and then there he was, a top story on the Globe and Mail online (Nobel Literature laureate Mo Yan is accused in patriotism lawsuit of insulting China’s heroes), March 13, 2024. I'd forgotten he'd won the Nobel Prize for Literature. He hadn't when I saw him. (His Nobel speech, December 7, 2012.)

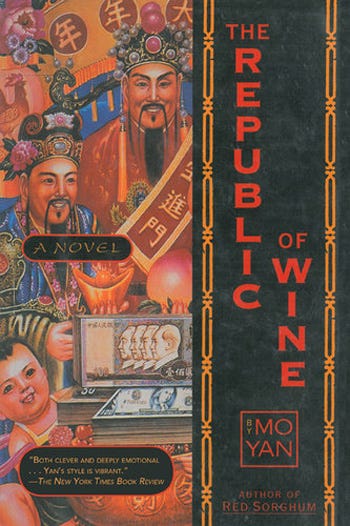

When was that? The year 2000, I believe, because that's the year the English translation of his novel, Republic of Wine (1992) came out. MAJ reviewed it in the Globe and Mail (my memory tells me so, but I cannot find a link online to prove it). He appeared at the Toronto Reference Library. He didn't speak English, but he submitted to an interview via a translator.

Incidentally, my favorite Nobel story is when Alice Munro won, and she sent her daughter to Sweden. The cutline to the photograph in the Globe and Mail said it all:

Jenny Munro, daughter of the 2013 Nobel Prize Laureate in Literature Alice Munroe of Canada, receives the Nobel Prize in her place from Sweden's King Carl XVI Gustaf, during the Nobel Prize award ceremony at the Stockholm Concert Hall in Stockholm, Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2013.

Is there a more Alice Munro name, a more small town Ontario of a certain era name, than "Jenny"? Jenny and Sweden's King Carl XVI Gustaf. Amazing.

Back to Mo Yan. I have a copy of The Republic of Wine, but I haven't yet read it. I read Yan novel Red Sorghum (1987): "this novel of family and myth is told through a series of flashbacks that depict events of staggering horror set against a landscape of gemlike beauty, as the Chinese battle both Japanese invaders and each other in the turbulent 1930s" (GoodReads). It was good.

Here's what I want to say about Mo Yan and me and The Year 2000: Yan told a story about how he was "allowed" to write his literary novels because he worked as a television writer, on a cop show. The Chinese Communist Party was flexible enough to say, yes, you can write what you want (Yan said), but it also said he needed to use his writer's gifts for something more useful: TV entertainment. He was asked, Isn't that insulting? He shrugged, good naturedly. It seemed a reasonable compromise. The CCP had allowed him to travel to the west, too, but he was going back to China. It was his home.

I have returned to this story time and again over the years, because it seems to say something about writers writ large. To me, it's not about the modernizing of the CCP or the authoritarian regime showing flexibility. Because, in the so-called Free West, what is different? The literary marketplace is desert, and popular entertainment genres dominate writers' expectations and opportunities more so than ever. Communism, capitalism, does it matter to the literary writer?

One difference, though, is that Yan said he didn’t get paid per copy sold. His books sold millions of copies in China. I believe he said he was paid a flat rate for the book. There were no royalties, or all profits went to the CPP publisher.

Yan also told a fascinating story about how he'd read, in Chinese, a 15,000 word essay about William Faulkner, and how that had shaped his literary vision. In his Nobel speech, he mentions Ol’ Bill. Faulkner, he said at the Reference Library, was writing about a society under stress from the effects of modernizing influences. This was Yan's subject, too. He wrote about how agrarian China was overrun by the 20th century. Communism, capitalism, did it matter? Modernization flattened societies. It was funny, though, that Yan said he hadn't actually read anything by Faulkner. Not in English, which he didn't read, nor in translation. The 15,000 word critical summary was all he needed.

The critique of Yan reported in the recent Globe and Mail article, I can tell you, also appeared at the Reference Library. An audience member got up and spoke harshly to Yan in Chinese (Mandarin or Cantonese, I don't know). The translator said Yan had been accused of making his Chinese community look bad. He wrote about the bad things. He ought to be ashamed. Yan was not. The confrontation reminded me of a 1962 event that Philip Roth often referenced, where he appeared with Ralph Ellison.

The event remains legendary, largely because throughout his career Philip Roth stated that the fierce interrogation of his work at Yeshiva was what made his bones as an author, confirming him in his attitudes toward religion and ethnicity.

The Newark Public Library played the tape of this 1962 event in 2021 at a conference to discuss the issued raised there. As the library's website states: "the issues that were discussed with memorable eloquence in 1962 remain with us in 2021."

No kidding.

***

I finished 2000 on Pender Island, spending my first Christmas away from my family ever. I had more time that I had ever dreamed of to write, and I wrote, some. I wrote enough to finish the novel-in-progress, but I had no big epiphany. There was no breakthrough. I made use of the in-house pasta maker. I made some mean blue cheese omelets. My girlfriend visited me, and we decided to make apple pie. I read out the recipe, and we went to the store to get supplies. We started to make the pie.

“Why do we have so many apples?” I asked (myself, who had been responsible for getting the apples).

I checked the recipe. Oh. Five apples. Not, five pounds of apples.

Loved TDR! Ah, 2000... By chance I came across a sweet review of an early version of my sound poetry, Incrementally.

I do enjoy reading about what a friend and fellow writer terms "the day to day despair" of the Writer's life. It reassures me that there are many companions on this road.