It’s called “1793 and All That” because, best I can tell (it could be 1797, though, evidence is sparse), either way, that’s when Nathan Bradley (1754-1833) and Elizabeth Harden (1760-1846), my 5th great-grandparents, brought their growing brood to Northumberland County in what would become Ontario, Canada, and was then known as Upper Canada, established 1791.

All of this was possible because of the Johnson-Butler Purchase of 1787–88 (also known as the “Gunshot Treaty”).

…of the earliest land agreements between representatives of the Crown and the Indigenous peoples of Upper Canada (later Ontario). It resulted in a large tract of territory along the central north shore of Lake Ontario being opened for settlement. These lands became part of the Williams Treaties of 1923.

The treaty was signed at Carrying Place, now part of Prince Edward County, at a location now a National Historic Site across the street from a gas station. I visited in 2022, blinked, and almost missed it.

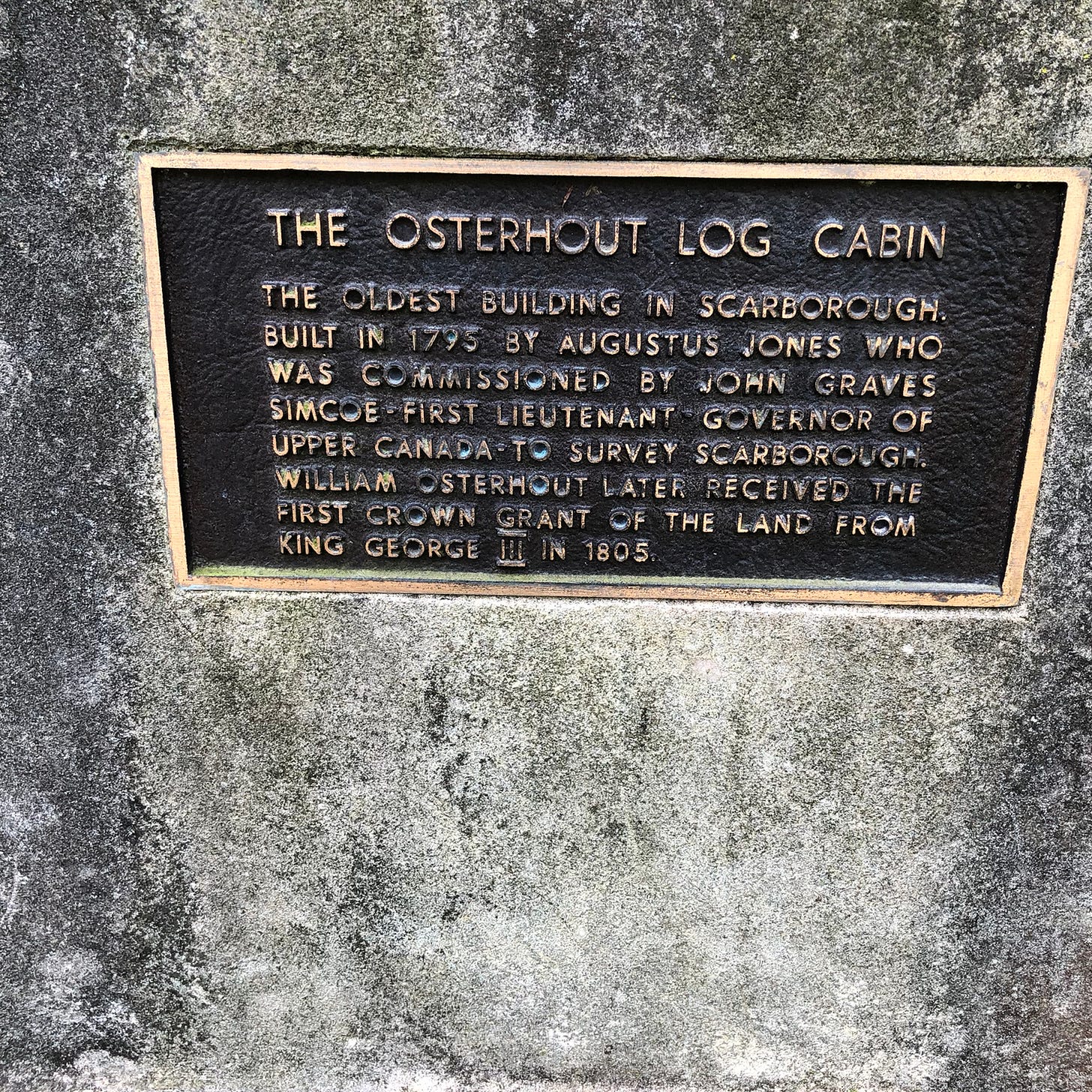

Tangentially, near where I live in Scarborough, Ontario, is a log cabin with its own plaque, noting its the oldest building in Scarborough. It was the surveyor’s cabin, literally home to the guy who drew lines to divide up the land, acquired for settlement by treaty, carving up the new colony, preparing for the arrival of folks like my 5th great-grandparents and, eventually, me.

These log cabins and plaques follow from the Royal Proclamation of 1763:

On October 7, 1763, King George roman numeral 3III issued a Royal Proclamation establishing a new administrative structure for the recently acquired territories in North America. He also established new rules and protocols for future relations with First Nations people.

The proclamation has 2 parts of significance:

defining the land west of the established colonies as "Indian Territories", where First Nations people "should not be molested or disturbed" by settlers and where the Indian Department would be the primary liaison between the Crown and First Nations people

prohibiting colonial governors from making any grants or taking any land cessions from First Nations people by establishing a set of protocols and procedures for the purchasing of First Nations land

Since its issuance in 1763, the Royal Proclamation has served as a basis of the treaty-making process throughout Canada, and is referred to in the Section 25 of the Constitution Act 1982. The proclamation, and the accompanying promises made at Fort Niagara in 1764, laid the foundation for a constitutional recognition and protection of First Nations rights in Canada.

The 1763 Royal Proclamation was also one of the grievances that led to the 1776-1783 Revolutionary War that established the United States of America.

Speaking of the Revolutionary War, the (Private) Nathan Bradley mentioned below, I believe, is the Nathan Bradley mentioned above.

Dorchester is in Massachusetts, and it’s where the Bradleys lived from about 1640 until the Revolutionary War. Nathan’s first cousin, once removed (his father’s first cousin), was Sarah Bradlee (spelling variation) (1740-1835), otherwise knows as the “Mother of the Boston Tea Party.” Ancestry tells me that Sarah is my first cousin, eight times removed lol.

Now, disagreement exists to the present day whether the Bradleys of Northumberland County, who appear in the first census of the area (1803) were United Empire Loyalists. I believe they were not. Who is a soldier in the Revolutionary Army, cousin of Boston Tea Partiers (it wasn’t just Sarah involved), and then Loyal to the Crown? There are Bradleys on the UEL list, but no Nathan Bradley.

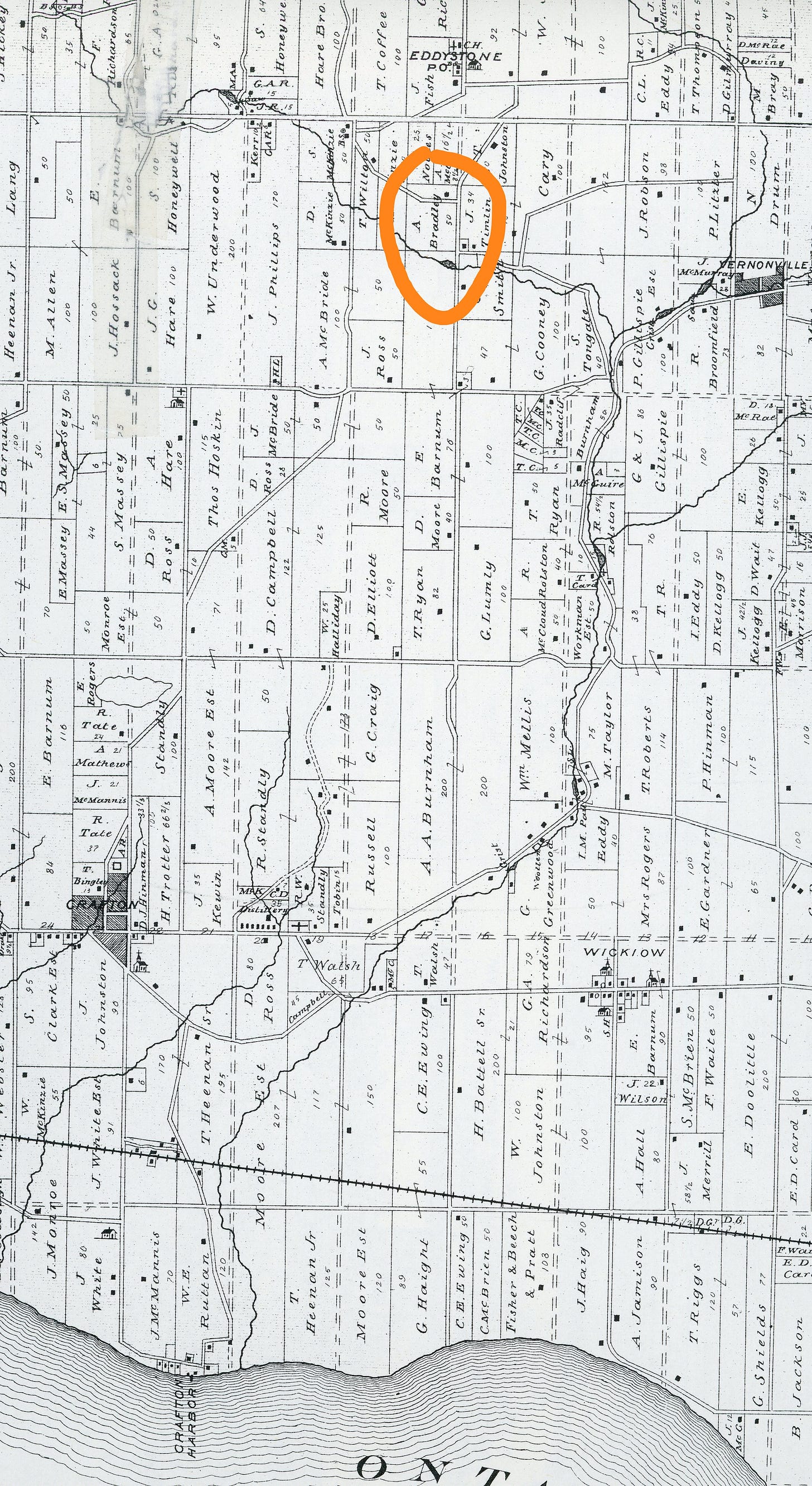

The main waves of Loyalists came to what is now Canada in 1783 and 1784. Nathan and Elizabeth came a decade later. They are on the first census of the area, 1803. However, there is reason to believe they had been there longer. For one, Nathan has a page at the National Library of Canada, noting a 1797 land petition. Not going to try to explain all of that here, mostly because I don’t understand it all, except to say that the land parceling and acquiring in that period was a mess.

Some folks (Loyalists) were given land grants, but by the 1790s the Upper Canada administration was seeking to attract settlers from the new USA with cheap land. They worked with land speculators, who recruited settlers in the USA and parceled out land (wilderness) to be “broken” and turned into farmland. At least, this is how I currently understand it, though I have a slow moving research project to seek out better sources and try to get a better handle on my confusion about the 1790s, in particular.

In Northumberland, the land speculator was Asa Danforth Jr., future building of the road to Kingston and namesake of Danforth Avenue. A colourful character about whom more stories should be told!

I know I haven’t said anything about The Life and Times of Captain N., but I’m getting there.

Poking around online and in libraries to help get a handle on all of the above, I came across a 2002 book of essays, The Revolution of 1800: Democracy, Race & the New Republic, edited by James Horn, Jan Ellen Lewis & Peter S. Onuf. Revolution of 1800? I thought. Hmm. In particular, there is an essay, “A Northern Revolution of 1800? Upper Canada and Thomas Jefferson” by Alan Taylor. This essay has a generous heaping of information about Asa Danforth Jr., both about his role as a road builder and a land speculator.

One of my main takeaways of this book, and related research, was — this world was wild, unruly, and a deep mystery to our contemporary minds.

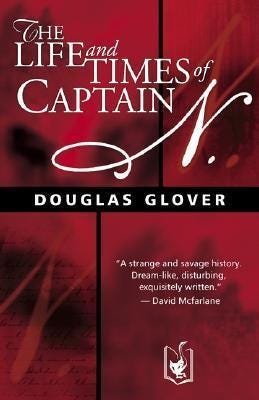

Which brings us squarely to The Life and Times of Captain N. by Douglas Glover, first published in 1993, then again in 2001.

(Counterpoint: the 18th century was wild and unruly, but it is not a deep mystery to our contemporary minds, because our contemporary world is also wild and unruly — and wild and unruly in ways so similar to the 18th century that we cannot help but recognize it, as if looking in a mirror. This point isn’t developed here, but I suspect I’ll be returning to it. It seems to me more right than the original assertion.)

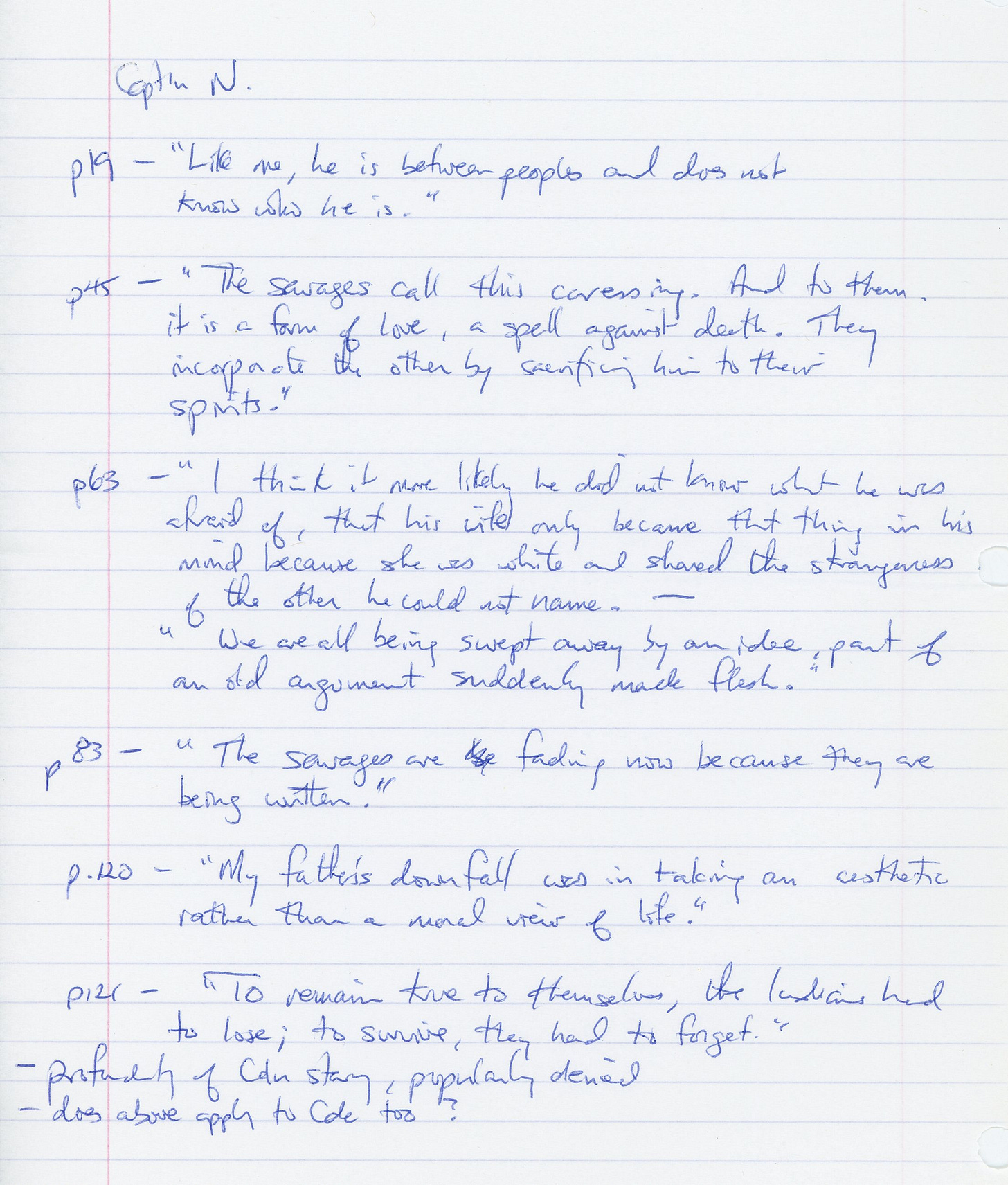

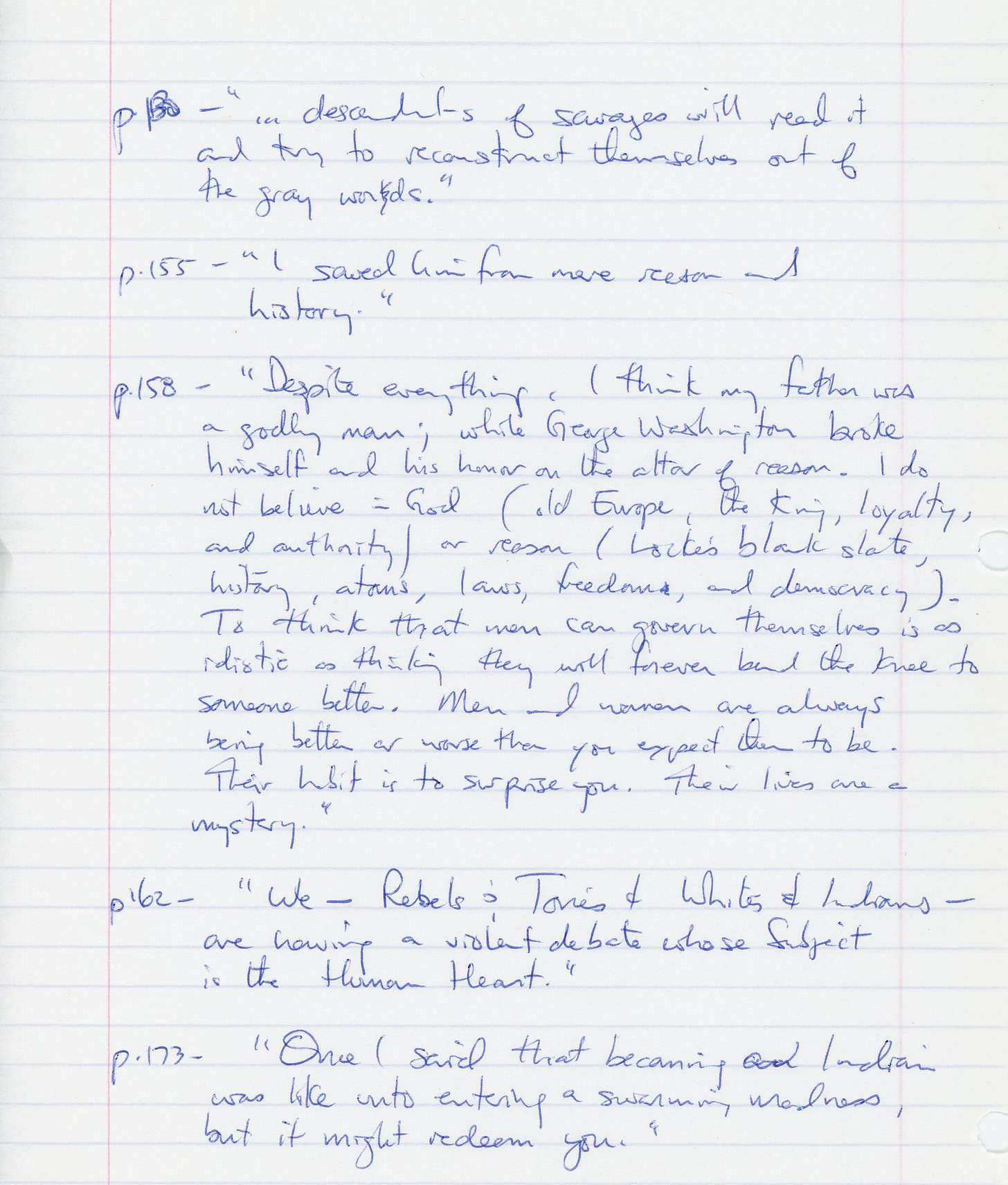

I recently pulled out my copy of the 2001 edition, and I found I had copied out various passages of the novel onto ruled paper and left them inside. More on them shortly.

How to summarize this novel? Goodreads summarizes it this way:

Set on the Niagara frontier in the final days of the American Revolution, The Life and Times of Captain N. sees the revolutionary new world order from the standpoint of the losers. Hendrick Nellis, a Tory guerrilla, has also been a redeemer of whites abducted by Indians. His son Oskar finds himself sometimes allied with the Indians, sometimes at war with them. Hendrick kidnaps Oskar for King George's army, and Oskar, haunted by dreams and by books, is the teller of the tale. The book he intends to write is sketched out in his letters to George Washington and in the signs tattooed on his skin as mementos of his personal Indian wars. The Life and Times of Captain N. trespasses into the no-man's-land where the delirium of combat drives races, genders, languages, and ideas into a primeval frenzy. Master of the psyche's primitive depths, Douglas Glover draws the reader into a violent and erotic emotional whirlpool.

Note: My 2001 review of the novel is part of the Douglas Glover collection on this blog, but I don’t intend to reference that review — and hopefully not repeat myself too much.

Captain N. is my choice for Canada Reads. It may not align with today’s sensibilities, especially on the CBC broadcast channels, but I will make my case, anyway. From the Goodreads summary above you get a hint. The novel includes a crush of competing narratives: the Loyalist, the Revolutionary, and the Indigenous. As we contemplate today what the 47th US President means when he talks of annexing Canada, we might be guided by memories of the 18th century, if we had any. Captain N. is full of them.

I’m not going to say that Glover gets everything right. It’s a novel within a historical moment, but it’s not a historical novel, as most would understand that term. To me, it’s a novel about language and the challenge of defining truth — even anything stable enough upon which to make a claim. Because there are a lot of claims being made, then and now, as there is a certain American President who lives in a “disinformation space,” and a certain American Vice President who recently said disinformation is so 1980s….

Here’s my 2001 notes:

That quotation from page 162 seems to sum it all up for me.

In 2001, I knew about Nathan Bradley, but what I knew was very little. Since my father passed away in 2017, and I inherited his family history material, such as it was, I have been much more interested in the story of my family’s past — and more confused about it. I have a direct connection to the Boston Tea Party? wha!

There are bits and pieces of what the Bradleys were up to in the 18th century. There is a snippet of a story that says the Bradleys were in Illinois, but one Bradley family historian told me that was unlikely. They were in upper New York State, back then perhaps in the part that is now included in Vermont. After being in Massachusetts for 150 years, why did they move? Well, the British occupied Boston during the Revolutionary War and the family of the Tea Partiers was likely unwelcome.

Nathan and Elizabeth’s first son, William Bradley (1777-1861), my 4th great-grandfather, was born in Onondaga, New York. Per Wikipedia:

Native Americans have inhabited the region for centuries. As early as 1600, Onondaga was a village that served as the capital of the Iroquois League and the primary settlement of the Onondaga people. During the American Revolution, the Onondagas sided with the British, and Onondaga was attacked by the Continental Army on April 21, 1779. After the war, the Onondagas were forced to cede their lands in New York to the new state, although some land was set aside to form the Onondaga Reservation. Most of the Onondagas left New York and were resettled in Upper Canada.

Among the papers I have from my father, one brief story is repeated. It goes like this. The Bradley escaped the US ahead of attacking Indians. In one version, it says “who burned their log cabin.” Goodness. One needn’t wonder why. Perhaps something of this sort happened.

What has struck me, looking into the 18th century and this part o the world, is the persistence of warfare. I mean, watch Last of the Mohicans (1992). Look past so much of it that is inappropriate now, and witness the warfare. It is total. The French, the British, Indigenous communities on both sides, the American frontier settlers just trying to quietly get along. Ahem…

After the Treaty of Paris, 1763, of course, quickly upon came the Revolutionary War. Then the Revolution of 1800. Look it up. Then the War of 1812. War, war, war. Like Oskar says in Captain N., the conflict, all around, defines us. Competing visions of reality, competing visions of the future.

When Nathan and Elizabeth arrived in Upper Canada, they already had seven of their 12 children. They were farmers and, I’m pretty sure, still Puritans. Definitely not Church of England, or Methodists, or Presbyterians, or Church of Rome.

Some of their children went back to the USA. Members of the family fought on both sides of the War of 1812. From this family, there are now hundreds, possibly thousands of descendants, probably all over the world. From a little poking around on Ancestry, one can easily see the family spread westwards across the continent in the 19th century, as colonialism continued to “open land.” I’m part of the family that hasn’t gone far from where Nathan and Elizabeth landed. My great-grandparents are buried in the churchyard down the road and around the corner from the Bradley homestead, which stayed in the family until the late-1800s, best I can tell. My grandparents, and my father now, are buried in the next town over.

Again, all of this is possible because of the Gunshot Treaty, the Royal Proclamation, and what eventually became the Williams Treaties and, ultimately, the Williams Treaties Settlement Agreement (2018). Government of Canada 2018 statement.

Yes, conflict defines us. Here’s to hoping that reconciliation, and stories seeking truth, can, too.

This is good, Michael. Nice to see you descending into the histo-genealogical fugue with the rest of us. But best of all it is good to be reminded of my book. That Goodreads summary is paltry. But your handwritten list of quotations is the best kind of reading. That puts the wind at my back.