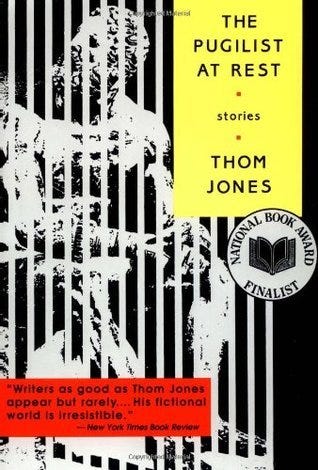

In 2011, I decided to read Thom Jones’s (1945-2016) short story collection, The Pugilist at Rest (1993). I’d first heard of it in 2006, when I asked a number of writers to send me a list of the stories/collections they would teach, should they be asked to teach “Short Story 101.” The list became a feature for The Danforth Review, the years 1999-2009 now warehoused on the National Library and Archives Canada site.

I also saved the feature in 2010 on my blog.

It was a fun feature. It also gave me a reading list. Craig Davidson suggested: “Anything by Thom Jones. Perhaps ‘The Pugilist at Rest.’” Why I turned to this specifically in the fall of 2011, I don’t know, but when I came to the story “I Want to Live!” I lost my breath.

That fall, my wife had been diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. Doctors immediately began chemotherapy. Again. The previous winter she had done 18 weeks of chemotherapy, now she had started the same all over again.

I remember lying in bed with her, each of us reading. Me reading Thom Jones.

“Don’t read this book,” I said to her. “It’s really good, but don’t read it.”

“Why not?”

“There’s a story in here about a woman with breast cancer, and it describes everything that is happening. Right down to the frequency and the names of the drugs.”

The title story, of course, is about a boxer. The book is filled with warrior spirit. Schopenhauer, the German philosopher (1788-1860), comes up a lot. But “I Want to Live!” is about a woman with cancer and the life force fighting extinction. John Updike included it in The Best American Short Stories of the Century (1999). On the cover is an image of the ancient Greek statue referred to in the title story.

I was living it.

I thought, How does he know this stuff? He must have lived it, too.

What I didn’t say to my wife: “Don’t read it, because she dies.”

She wants to live! And she dies.

My wife died, too. Six months later. She wanted to live more than anything. It didn’t matter. The pugilist rests.

2016 feature on Jones in The Guardian

*

To write this piece, I re-read The Pugilist at Rest. It contains what I remember. Violence. War. Philosophy. Drama framed between deep meaning and existential despair. Think Nietzsche. Think all or nothing. There are repeated references to Schopenhauer too.

We are like lambs in a field, disporting themselves under the eye of the butcher, who chooses out first one and then another for his prey. So it is that in our good days we are all unconscious of the evil Fate may have presently in store for us -- sickness, poverty, mutilation, loss of sight or reason.

This quotation is from the title story and is preceded by the phrase: “That august seeker of truth, Schopenhauer, was correct.”

For me, my wife 2011, was not a year of the “unconscious.” It was a year of complete awareness, or in the phrase of Jon Kabat-Zinn, Full Catastrophe Living (1990).

After the end of her first 18 weeks of chemotherapy in early 2011, doctors scheduled a radical mastectomy of her left breast, after which they said they could detect “no evidence of cancer.”

I asked if that meant the cancer was gone, even though I knew the answer. I wanted them to say it.

“We can’t say the cancer is gone. We can only say that if it’s there, we cannot detect it.”

They hoped that it was gone. The surgery had been conducted “with clean margins.” Within the margins cancer might remain, but they then sent her for five weeks of radiation therapy — to burn out whatever cancer might be left.

The specialist said, “I hope to never see you again.”

Hey, ditto, man.

But through the summer the promised pain relief never happened, especially in her lower back. We rented a cottage for three weeks in August, hoping by the end of it that some sort of normal would appear as the kids went back to school. But instead Kate was confronted by the moms in the schoolyard and their expectations that “it was all over now.” I told her, fuck them, and fuck her employer, too, who was asking when she was coming back.

“All you need to do is focus on getting better. Until then, we will fight the bastards.”

One Saturday in early October she asked me to press on her abdomen.

“Feel that?”

Yes, there was a hardness where there should have only been softness. We went to emergency, where an ultrasound indicated there was something there. She burst into tears, and the emergency room doctor said, “You’ve been through this before, you’ll get through it again.”

Don’t they teach anything about metastatic breast cancer in medical school? Once it returns, life expectancy rapidly plummets.

The specialist who didn’t want to see us again, saw us again. He ordered an immediate new 18-week course of chemotherapy. He wasn’t going to wait for any more test results.

“We can assume it’s cancer.”

Up to this point, I had resisted Googling any medical questions, but I did then. Life expectancy of metastatic breast cancer? 7-9 months. (She would live 8.)

We knew the routine. We fell back into it. Six trips to the chemo ward, three weeks in between. Christmas came at a “good time,” and we planned a special trip away with the kids. The Last Christmas? We hoped not. She, for sure, had not given up hope on a miracle. I was feeling increasingly crushed. If she died, what would happen? I could lose her, I told her, but not her and the kids (my step-kids). She had no capacity for this conversation, and I did my own research. Through work, I spoke to a family lawyer. I explained the situation and asked how I keep my relationship to the kids.

“Why would you want to?” she (!) said. “You have no obligation to them. You’d be free.”

I hung up.

I called the service and said this wasn’t the type of legal advice I wanted. I was assigned a second lawyer, a man this time, who walked me through the law, the options, sensitively. My wife and her ex-husband shared custody. If and when she died, he would assume rights and responsibilities. Full-stop.

(We would work out an arrangement after her death, for me and the kids to continue, for which I remain forever grateful.)

Another memory. Around this time, Kate’s parents told her they’d been thinking about it, and they couldn’t take the kids. Kate laughed. “No one was even considering that! They have two dads!”

*

Some years, so full of incidents in memory, last longer than 12 months, and 2011 for me feels like a decade, if not two. The progression of disease is one way of tracking the months, but it’s not the one I remember most. In Cat’s Eye (1988), Margaret Atwood references models of time. She’d been reading, I’m sure, A Brief History of Time (1988) by Stephen Hawking. At one point, she describes time as a pool: different events rise to the surface in sequence. In memory, that sequence can get moved around.

Events that rise to the surface for 2011 for me are things like a birthday party for a seven-year-old, her mother bald from chemo but still focused on making the party all about her little girl. As that first 18-week chemo ended, my wife rang the bell at Princess Margaret Hospital. She said she would never do that again, no matter what, but eight months later she didn’t hesitate to let them hook her up to the drip. When the first 18 weeks ended, I was exhausted, everyone was. Six three-week cycles of poison and recovery is beyond terrible, yet you focus day-to-day to get the kids to school and everyone fed and the in-laws pampered. I mean, they were there “to look after her,” but who was looking after whom? We kept coming up with projects around the house to keep my father-in-law occupied. A new wall across the basement to create a storage room? Sure. A new banister down the stairs to help with stability? Sure. Friends had provided us with multiple packages of frozen food, so we wouldn’t have to cook. But someone had to defrost the meals. One day my father-in-law said he had some advice. I should take the food out of the freezer before I went to work in the morning! Fabulous idea! And why are you hanging out in my house all day again? So I can come home from work — and then arrange supper for you???

My in-laws were English and had lived through WWII. One day my wife told her mother that she felt like she was living through a war. Her mother said, “You don’t know what it’s like to live through a war. You have a disease!” (And yet a year later they were alive and she was dead.)

As the first chemo rounds ended, my manager suggested I call a therapist through the Employee Assistance Program. I did, and the advice I received was to take two weeks off and do nothing. Calm down the nervous system. And by nothing, the therapist meant: lie in a dark room and stare at the ceiling. Great advice, I supposed, but no way my wife was going to be my caregiver so I could do that. The kids needed to be fed and escorted to their activities. Laundry needed doing, homework supervised. But Kate and I got away for a weekend in March to an old farm house that friends of a friend had, sitting empty. Spring was springing, snow melting, water flowing. It was a magical two days, feeling separated from the world we’d left behind. A memory like a clear chime of a bell.

We tried to create as many of these kinds of moments as we could. We went back to the farmhouse in the fall, just before the metastases, but the vibe was dark. It was the weekend she took herself to emergency. That was also the weekend of a street hockey tournament fundraiser, and one image from emergency, Toronto General, was a young man busted up from some street hockey malade event. He was full of brio, adrenaline. Made his feelings known to all of us, to his mother’s horror.

On the way home from the hospital, Kate directed me to the LCBO. She called some friends. “We’re not going to think about this right now. We’re going to get some people together and have a good time.” Her friends came over. There was no talk of what had just happened or what was about to happen.

In fall 2010, Kate’s GP recommended Kabat-Zinn’s Full Catastrophe Living. It was a book Kate appreciated. She went straight from her GP’s office to Indigo at Bay and Bloor and bought the book. She also bought some branded KEEP CALM AND CARRY ON products, including a water bottle, which I continue to use as my overnight bedside water supply. But by 2011, I thought more support could be provided than that book, which tells the story of meditation workshops for people with cancer. Were there not meditation workshops in Toronto we could join? Kate called her GP. Oh, yes, there were. Did she want to be signed up? She did. I went to my GP, and I did. This was a mindfulness group. At the first meeting, folks sat in a circle and introduced themselves. Why were they there? Lots of sleep disorders, one university student with exam stress, Kate said: “I have terminal cancer.” First time I’d heard her say that. I said: “I’m married to her.” I still tell people that the mindfulness meditation workshop group and practice was the best thing that came out of that cancer period. Kate was on lots of painkillers, but DOING meditation wasn’t a passive thing. It wasn’t popping a pill. It was an ACTIVE practice she/we could do. (Why did we have to ask for it? Why didn’t the GP offer it up right off the top?)

In early 2010 — pre-cancer — Kate had started a blog, Auntie Cake’s Shop. I had a literary blog, and she thought she could do a happy life blog, but it became something else. It was her communication tool to her communities, where she could reflect of the experience of living through cancer and also keep folks informed. She thought it would eventually provide fodder for a book, which she planned to call THROUGH THE BLACK HUMOR. She had a fantastic sense of humour, and she wanted to show that she could go through all this darkness and stay herself. In that, she succeeded, straight to the end.

I’d put my online literary magazine, The Danforth Review, on hiatus in 2009, but in summer 2011 I decided that I would re-start it on a smaller scale. I would accept submissions for fiction and do occasional interviews and whatnot. It relaunched in September 2011, a month before the metastases, and I published it monthly until 2018, without fail.

I see from the record, that in 2011 I did a post-a-week on the blog. Very little of this still exists in my memory, but I see I reviewed and reviewed and reviewed. Being engaged with books was more than a decent distraction; it is one of the deep currents of my life. Kate was digging into her own deep currents, cooking, gardening, child rearing, friendships, reading — and we encouraged each other. Live deeply!

I made an e-book version of Only A Lower Paradise (though later I unpublished it). I made a sampler of my short stories similarly and similarly unpublished it later.

And I published two short stories:

Did I say we went to the cottage for three weeks in August? I did. That was a major event and a major expense, something that hasn’t been repeated. It’s the most time that I’ve spent at a cottage, ever. I sometime think that was also the last time I felt “normal,” whatever that means. I was determined to be optimistic and believe the cancer period was coming to an end. Kate didn’t want the cancer period to change her, and here we were, transitioning back to our regular lives. I brought a pile of books and sat in the recliner and wrote book reviews for my blog. I remember, specifically Clark Blaise’s The Meagre Tarmac (2011), which I thought was fantastic and deserving of far more attention. Still.

We swam daily off the dock. Friends and Kate’s brother and nephews visited. We slept late. We cooked a Turducken in the enormous BBQ. Turducken? It’s a turkey stuffed with a chicken stuffed with a duck. The chicken and duck need to be de-boned. That was my job. It took ... hours. The meal prep took two days. Go big or go home, that was our mantra. It was a life event, that’s for sure. Thanksgiving in summer.

At the cottage, we also celebrated our fourth wedding anniversary. I had seen in a travel magazine that a restaurant in Gravenhurst, named North, was one of the best in Canada. Surprise?! “Let’s take the kids there for our anniversary,” I suggested. The drive to Gravenhurst was an hour, but we all got dressed up and went to North, which turned out to be housed in a former Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise building. They were surprised to see a family so well dressed show up mid-week, late summer, but it was fun, memorable, and near the childhood home of Norman Bethune (1890-1939), so we got to see that too. LOL.

It was our final wedding anniversary. I guess I don’t need to say that? But I can’t think about it without thinking that. The seven-year-old on that day is now 21, and she still remembers that place we went to in Gravenhurst. “North?” Yep.

North is now The Oar, I believe. It still looks excellent.

Here’s a passage from “I Want to Live!” by Thom Jones:

On the morphine she was walking a quarter of an inch off the ground and everything was . . . softer, mercifully so. Maybe she could hack it for a thousand miles.

But those people in the hospital rooms, gray and dying, that was her. Could such a thing be possible? To die? Really? Yes, at some point she guessed you did die. But her? Now? So soon? With so little time to get used to the idea?

Here’s another:

Only an arch fiend could devise a dilemma where to maybe *get well* you first had to poison yourself within a whisker of death, and in fact if you didn’t die, you wished you had.

This latter quotation resembles a sentiment Christopher Hitchens published in the fall of 2011 in Vanity Fair, a copy of which Kate read in the chemo ward, and said, “Yup.” Hitchens was dying that fall, too, and not blogging about it, but writing about it in a series of essays that were posthumously collected as Mortality (2012).

...one thing that grave illness does is make you examine familiar principles and seemingly reliable sayings. And there’s one that I find I have not saying with quite the same conviction as I once used to: In particular, I am slightly stopped issuing the announcement that “whatever doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.”

In fact, I now sometimes wonder why I ever thought it profound.

In the brute physical world, and the one encompassed by medicine, there are all too many things that could kill you, don’t kill you, and then leave you considerably weaker.

A bit more Hitchens from the same essay (Chapter VI, in Mortality):

I now can’t summon the memory of how I felt during those lacerating days and nights [of radiation treatment]. And I’ve since had some intervals of relative robustness. So as a rational actor, taking the radiation together with the reaction and the recovery, I have to agree that if I had declined the first stage, thus avoiding the second and third, I would already be dead. And this has no appeal.

And there it is, the life force. “I Want to Live!”

While 2011 was in many ways a terrible year, in my memory it isn’t, probably because the first five months of 2012 were so much worse, but also because I had a front row seat to Kate’s life force. Against such an assault on her body, mind and soul, she was heroic, a word I never use lightly. I told her she was my hero, and it is against her example that I still seek to be.

A story. In late 2010, we were in clinic at Princess Margaret Hospital, a check-in, and it wasn’t her regular specialist who walked through the door; it was Dr. Robert Buckman (1948-2011), who appeared with some frequency on television and was author of Cancer is a Word Not a Sentence (2001). He was well known in medical circles for workshops on how to communicate with patients, and just the weekend before our visit to the clinic he had reviewed in The Globe and Mail (Nov 19, 2010) The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer (2010) by Siddhartha Mukherjee. Kate had read the review and immediate struck up a conversation with Dr. Buckman. He was curious: What did she think of the book? He made her feel the centre of all attention in the world, asking her more than once if she had any questions about her situation, next steps, anything. He would not leave until all of her questions were answered. We knew the clinic was busy, and he did not have all of the time in the world, but he made her feel he did. For her.

Hero.

As this story illustrates, Kate was engaged intellectually in her, to use Jones’s word, dilemma.

Here is a blog post by her, immediately after our time with Dr. Buckman in clinic:

Monday, December 6, 2010

100 Days of Citizenship

So, Tuesday will be 100 days of cancer. [Not that I am counting]. As Susan Sontag say - Illness is the night side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well, and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

So, 100 days of citizenship in that other place. Like standing on the border, feet firmly planted on hostile soil, looking across at the really truthfully greener grass.

But there were probably countless days before, unknown to us. We were hostages then, but unaware. I wonder, truly awed, at how that is even possible. How does your body become host to an invading marauder without you knowing? Like the Gauls and Romans at war without a speck of dirt being moved. What kind of sick feckless cruelty is that? Thank God we cannot see the future.

How does the human body, with its millions of cells, do it? What molecular miracle is happening, when the little dots start to mutate, grow, without the host even knowing they are there? Imagine. Over a period of time, your body stands to be overrun by invaders, but entirely without even a whisper of a sound. Nothing. Not an iota of change apparent, not a hair out of place. How insidious is that? Cancer is a perfect weapon. You don’t even know it. It lurks. But no, wrong term, it invades. It insinuates its way into your crevices and vessels, binds itself to them, and then audaciously invites more, more, more to the table.

As Dr Siddhartha Mukherjee says in the prologue to his book (p. 6) The Emperor of All Maladies - A Biography of Cancer - That this seemingly simple mechanism - cell growth without barriers - can lie at the heart of this grotesque and multifaceted illness is a testament to the unfathomable power of cell growth. Cell division allows us as organisms to grow to adapt, to recover, to repair- to live. And distorted and unleashed, it allows cancer cells to grow, to flourish, to adapt, to recover, and to repair - to live at the cost of our living. Cancer cells grow faster, and adapt better. They are more perfect versions of ourselves.

Blissfully ignorant of its existence, we went on trips, ate out, read books in the sun, played with the kids, went to work. Lived our life.

And now, painfully aware, we go on trips, eat out, read [different] books in the sun, play with the kids, go to work. Live our life.

For Michael, that means the office; for me, it varies. Fighting is my job now - I must often retreat to the core of myself to garner what strength is required to regain citizenship in the kingdom of the well. Usually, that means, to bed, or to rest on a soft surface somewhere. Sometimes it means escape in a Swedish series of books about a crazy lady, or writing this blog, lunching with friends, wrapping Christmas presents to Ella’s Swingin’ Christmas at Volume 11. It also means plugging into machines and swallowing poison, assisting with all manner of broken spirit, and crying. A LOT of crying. Fountains and rivers of liquid salt. It is a job you are not prepared for, in fact, dread. Worse than any mundane task or other related duty as assigned. But life, that unbending and strong coursing river, keeps you moving along. Really, there is no choice. Kind of like blood through your veins.

This citizenship requires no entrance test and there is no pomp, in fact a dearth of any civil ceremony or official acceptance - cancer is a despotic dictator, not a democrat; but I predict fanfare and flourish, pomp and circumstance, pins, certificates, balloons and a band playing when the tide turns and we resume life in the kingdom of the well. And a cake, of course.

xo KO

A year later, she was digging deep:

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Water, water, everywhere

There’s gonna come a time when the river’s gonna rise up high

There’s gonna come a time when the river’s gonna rise up high

And if I can’t swim, I gonna find my way to fly

(P. Reddick, Hook’s in the Water, Villanelle)

An overwhelming series of days. Washed over with pain. Beaten into physical submission. Time has ground on, and the sheer physicality of this disease has worn me to a nub. It makes every nerve ending raw. It wearies us all, frankly, and the vale of tears flows frequently around here, as our souls bridle at the rottenness of our luck. It sucks to be sick all the time; to be unable to move from fatigue and pain. It sucks to watch it, witness, be part of it. It sucks to have your loved one unavailable, on many levels, because of cancer.

I had a note from a friend today in which she made a request. She asked me to delve deeper. Tell what I find. Go down the path to the inner mind and pull it up at the roots. Shake it out, and see what falls to the ground. This particular friend never asks that which cannot be borne. She is the only person I ever really speak of the spiritual life with, I would say. So, here goes.

My spirit is sad, bludgeoned by reality. The spirit knows there is an army out there to protect it, but it is still reeling from the what ifs, the bad news, the sheer monumentality of this thing, this cancer. I too am sad. I am bone-tired sad. My heart breaks daily, when I go along the mental paths, threads of feelings, dropped and picked up at various points along this journey. The thoughts which plague me the deepest - of which I can barely give voice to - are the ongoing threads concerning my children. I feel so angry and bereaved on their behalf, spinny with fear and grief, panicked about the million mundane details of a life perhaps not to be witnessed. I find my inner voice catching, as I begin a proto-thought - I must remember to tell N about X, or make sure O knows how to do Y - this week I fretted that his current grammar and punctuation skills would not get him through adequately to high school. Will I be there? Should I tell him the secrets I know about girls, so he is armed, in advance, in case I am not here for him to weep to when the certainty of unrequited love hits? I want to tell my children all the things I need them to know, from me, with my voice. But when? Now? What if I die and don’t get to it? It prays on my darkest fears of death. For me and for them.

Then there is the mental path that inevitably leads to death itself. And the lingering question of spirituality, in the face of it. Am I afraid? Yes. And what exactly am I afraid of? Of a prolonged painful horror my loved ones have to witness. There it’s been said. I said it. I am afraid. I am scared shitless. I know, thank God that I am not alone, and others share my fear. Natural really, as we are all afraid of what we do not know. Do I contemplate finding a place of religious haven in this my time of need? Well, yes. I do. I was raised a Catholic, and it fed my needs as a child. Not so as a grown up. The rites of passage are very clear in the Catholic faith - absolution, forgiveness. But at this point, what do I believe in? How does one go about a spiritual or religious reclamation? Excellent question. And I promise to give it a LOT of thought. I am envious of those with strong religious grounding and tenets; these are the times when they sure do come in handy.

Humans are amazingly resilient, adaptable. I have done a fucking great job of adapting to this cancerous life - I live, eat, breathe, sleep as myself - there is no pretense of anything, really, anymore - it is an intense self-tutorial in real time. Michael is bone-weary but iron clad - moving it all forward without complaint, but often angry with this deal - and there is an immense sadness, too. The kids are steady in this storm, with an amazing capacity for beauty and love and cheer. Lawrence too, stalwart, there for us, keeping things moving along.

And mostly, we keep on moving. Even if you are lashed to the deck, breathless in the wind, and blinded by rain - eventually, the ship you are on moves forward, and the seas calm (ok, that metaphor is stolen right directly out of the Cat’s Table - M Ondaatje). It is unsustainable for anyone to live in a maelstrom. You drown. And so we rise to the level of the flood water, and help each other out, and fly.

I wish at this point I could just stop writing and turn over the microphone to her. Not possible. I am the one who’s left to remember, remind, record, reflect. It is strange to see my name in these posts: “born-weary but iron clad.” Oh my fucking God.

*

“I Want to Live!” is a long story, 24 pages. A catalogue of suffering and response to suffering, otherwise known as the Will to Live. The character, Mrs. Wilson, declines, she moves in with her daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter, the son-in-law reads Schopenhauer.

One afternoon after he left for work, she found a passage circled in his well-worn copy of Schopenhauer: In early youth, as we contemplate our coming life, we are like children in a theater before the curtain is raised, sitting there in high spirits and eagerly waiting for the play to begin. It is a blessing that we do not know what is really going to happen. Yeah! She gave up the crosswords and delved into The World as Will and Idea. This Schopenhauer was a genius! Why hadn’t anyone told her? She was a reader, she had waded through some philosophy in her time — you just couldn’t make any sense of it. The problem was the terminology! She was a crossword ace, but words like eschatology — hey! Yet Schopenhauer got right into the heart of all the important things. The things that really mattered. With Schopenhauer she could take long excursions from the grim specter of impending death. In Schopenhauer, particularly in his aphorisms and reflections, she found an absolute satisfaction, for Schopenhauer spoke the truth and the rest of the world was disseminating lies!

As I’ve been working on this piece, other memories have popped to the surface. I remember as Christmas approached one of Kate’s work colleagues dropped off a quilt she’d made for her. A comfort quilt. Kate and I were drinking gin and tonic on a Sunday afternoon. Did the colleague want one? I made one. It was very stiff, and the friend just left it, untouched. Were we drinking too much? Well, yeah. “What’s it going to do, kill me?” I heard Kate say more than once. No, it won’t, but also, sort of, yes. She didn’t read Schopenhauer. I told her not to read “I Want to Live!” Then in 2014, I had my own health crisis.

Kate called Princess Margaret Hospital to ask about family support services. For me. She lined up a psychiatrist, and I started to see him. Once a month. At my first visit, he said he wanted Kate to come for the second visit. He asked her what her biggest fear was, biggest concern. The kids, of course. Leaving them. He said it might not be much consolation, but the kids were 7 and 11 and research said 90% of a parent’s influence is in the first seven years. She had already given them 90% of a lifetime’s parenting. It wasn’t much consolation, but it sort of was, too.

The psychiatry was an extension of the palliative care, which by the end of 2011 was starting. Sort of. I went to nearly all of Kate’s medical appointments, but I didn’t go to her first consultation with the palliative care team, and I don’t know what happened. The report I got from her was, when the time is ready, they will be there, but I have suspicions that they talked about how to anticipate death, and she didn’t want to have that conversation, and didn’t want me having that conversation. Not yet.

We agreed (she insisted) we not talk about death until after Christmas. “Let’s just have as normal a Christmas as we can!” Which we did. But the issues we were ignoring were always at the back (sometimes front) of my mind. Some level of denial was necessary, sure, but denial is not a sustainable strategy for resilience. The mindfulness suggested to stay in the moment, but finally I said to her, “We have to plan for the future. We have to anticipate what’s coming. We can’t simply be reactive.” So as the calendar turned into 2012, we started to do those things: find a grave plot, updated wills.

In November 2011, Black Friday, I bought an iPad, our first, for myself, I was so curious about it, and Kate said, do it, get it! Instantly, it was no longer mine. It became Kate’s — for communicating, games, and fooling around. Immediately there were weird filtered photographs of her and the kids. It went to all medical appointments, an essential waiting room tool.

*

In January 2022, I wrote an essay on this blog: “Two ‘C’ Words — Reflecting on Cancer, COVID and Uncertainty.” If I had a TED Talk, it would be about this. It would be about 2011. It would be about resilience and managing through suffering. It would be about the Will to Live. It would be about how in the 14th month of cancer we got an iPad and took silly filtered photographs and played Candy Crush.

Wherever you are, John Lennon sang, you are here. Did he sing that? He had that “You are here” t-shirt. Was there a song too? (Looks it up.) “You Are Here” (1973). From the album Mind Games. Mind games, huh?

As I write this, we are at the start of the second winter of COVID-19. We are tired, confused, eager for the return of so-called normal. It is more a mental struggle, an emotional struggle, than a physical one, though the deaths are real and the suffering is real and it is the vulnerable who are most vulnerable, as it always is, as they always are. COVID is a “C” word like that other “C” word that grinds you down with mind games. The crab, cancer. As the COVID curtain came down in March 2020 and we all started working from home (okay, not all of us, just the ones who could, the lucky ones), we asked ourselves, “How are you doing? How are you adjusting?”

Such a weird moment in time! How will we explain it to others who were not there? How will we remember the past that is gone, the routines and assumptions about routines that have been broken forever? “How are you doing? How are you adjusting?” My answer was, “This reminds me of the cancer time. Living with a new uncertainty, surrounded by potentially catastrophic risk, the destruction of what we used to call ‘normal,’ its replacement with what?” The day-to-day, I told people. “This is what we learned from cancer, how to focus on the essential, how to let go of everything else, how to live in the moment and not worry about tomorrow.”

Because life. It’s what’s right in front of you.

*

Throughout 2011, I continued with my day job at the Ontario Public Service, with a supportive manager and colleagues. Everyone knew what was going on, and everyone had no idea what was going on. We just got on, kept at it. As one does.

*

On Schopenhauer

First, I feel the same way as Mrs. Wilson: I’m a reader, I have waded through some philosophy in my time — I just couldn’t make any sense of it. The problem was the terminology! I’m no crossword ace, but words like eschatology — hey!

I checked my bookshelf for that Schopenhauer book I thought I had. Turns out, yes: Essays and Aphorisms (1970 Penguin edition, originally published 1851 as Parerga and Paralipsomena). I bought this volume because of Thom Jones, I’m sure. The bookmark is stuck on page 46, but I did read the introduction by R.J. Hollingdale, because it’s marked up, slightly:

All other kinds of knowledge amount to establishing relations between ideas, but knowledge of oneself would be knowledge of immediate reality. And this is what Schopenhauer maintains knowledge of oneself actually is. We know ourselves objectively, in the same way as we know all other phenomena, as an object extended in space and time: we know ourselves as body. But we also know our own existence, and we possess feelings and desires. This inner world Schopenhauer calls ‘will’: we know ourselves as will. And thus there follows the ‘single thought’ which, properly understood, Schopenhauer says constitutes the whole of his philosophy: ‘My body and my will are one.’ My body is the phenomenal form of my will, my will is the noumenal form of my body: my body is ‘appearance,’ my will ‘the thing itself.’

The story of Mrs. Wilson, the story of Kate, the story of Hitchens, is the battle for the body, the battle of the will. To live.

More of Schopenhauer you can find elsewhere. Last word here to Jones:

There was more and more pain and discomfort, but she was laughing more, too. Schopenhauer: No rose without a thorn. But many a thorn and no rose. The son-in-law finessed all of the ugly details that were impossible for her. Of all the people to come through!

Amen.

*

This was a gut wrenching read I couldn't put down. I'm so sorry for your tragic loss.

What a powerful reflection. It makes me wonder, how often do books mirror our lives in such profound, sometimes painful ways? Such an insightful piece.