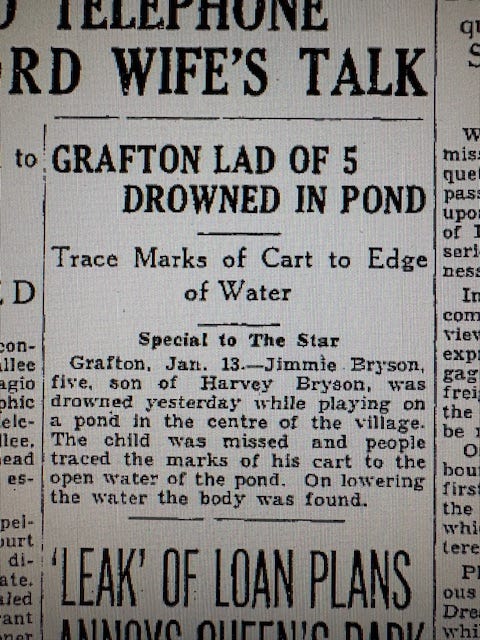

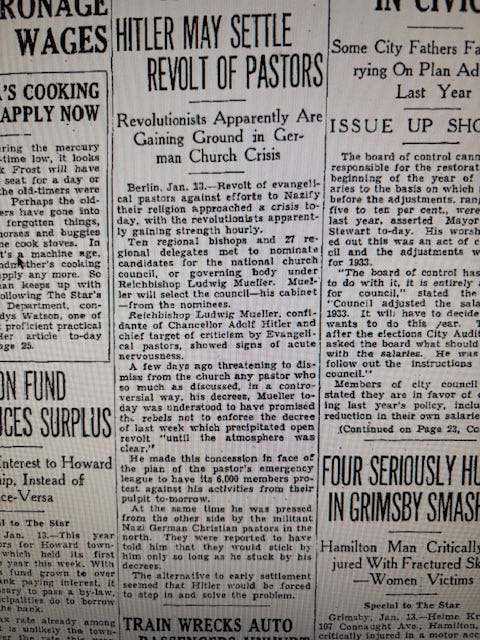

On January 12, 1934, my uncle Jimmie, aged four, plunged through the ice of a pond in the town near the shore of Lake Ontario and drowned. His death made the front page of the Toronto Star and has affected the lives of dozens down the present day, 90 years later. Upon re-examining this page, I see the Nazis also made the news that day, evidence of the fascist take-over of Germany creeping ever wider. Day-by-day.

In 2014, I published on the Numero Cinq site a mixed memoir/essay on grief and "after the end," a follow-up to the memoir/essay I'd written on Mrs. Dalloway and Waiting for Godot in the weeks after my wife's death from breast cancer in 2012.

The initial essay was about, in a general way, returning to reading after a mind/heart blasting traumatic event. The new essay was grounded in the realization that after the trauma there is no return to status quo; there is a new reality "after the end."

What was that? I had a sense that J.G. Ballard (1930-2009) returned to that subject time and again.

Ballard, as a child, was taken prisoner by the Japanese (1943-45) during World War II, events later captured in his memoir, Empire of the Sun (1984), later a movie (1987) adapted by Tom Stoppard and directed by Steven Spielberg. A quotation from Wikipedia (copied January 7, 2025) sets the context:

Concerning the violence found in Ballard's fiction, the novelist Martin Amis said that Empire of the Sun "gives shape to what shaped him." About his experiences of the Japanese war in China, Ballard said: "I don't think you can go through the experience of war without one's perceptions of the world being forever changed. The reassuring stage-set that everyday reality in the suburban West presents to us is torn down; you see the ragged scaffolding, and then you see the truth beyond that, and it can be a frightening experience."

Ballard would marry and have three children before his wife, Mary, died of pneumonia in 1964, leaving him to raise the children alone. Overall, to generalize significantly, he would go on to write novels and short stories depicting a violence-stained world. He also wrote non-fiction, created art, and gave generous interviews, where we often find him outlining about his theory of the case. By which I mean, his attempt to articulate "the truth beyond that," and the relationship between the mask and drama of violence and the nature of our world.

What I'm getting at here is not the trauma plot or shifting notions of horror. I'm interested more in a question like, how to make art in a world destroyed?

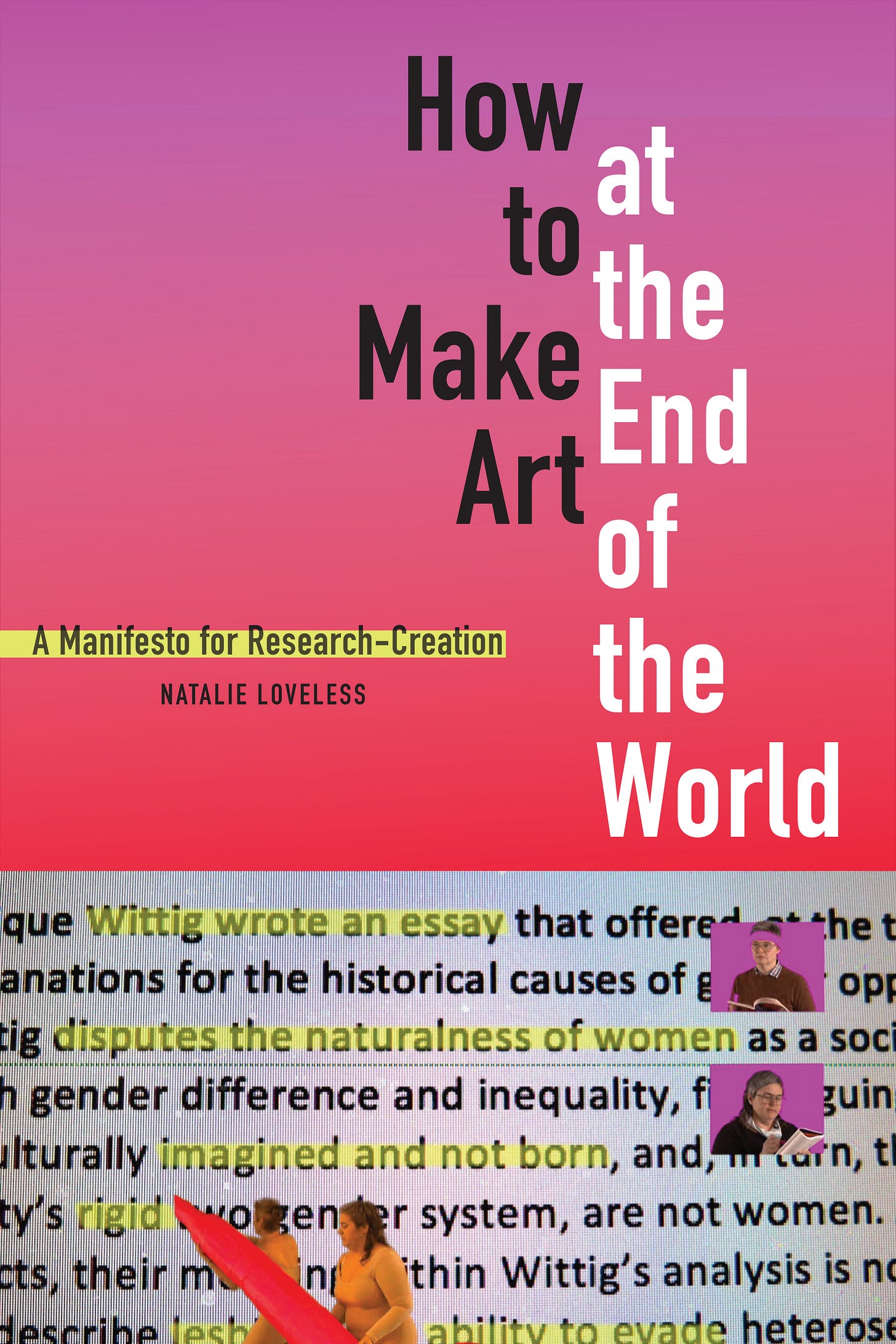

Later, I would find Natalie Loveless's How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation (2019), which I'll say more about below. I would also contemplate approaches to storytelling and art making by others who have lived through catastrophe. The list can become long, once you start to think about it, but initially the top of mind ones were, of course, the Holocaust (see Primo Levi), settler-colonial impacts on Indigenous communities, 21st century environmental crisis. In Palestine, the word is literally catastrophe: Nakba. In Mrs. Dalloway (1925), it is shell shock from WWI. For my grandparents, it was the loss of their first born. For me, the loss of my wife, the end of our dream. The loss of a sense of control of my destiny (hubris).

My grandfather died in 1963, before I was born, and my grandmother died in 1983, when I was 14. She was one of the strongest people I have ever met, a transcendent personality. After the death of my wife, I thought of my grandmother, who was only ever a widow when I knew her. When my grandfather died, she had three children still at home, then aged 19, 13, and 9. She played organ at the church and gave piano lessons. Hard times were upon her. She got a job with the township and took courses in municipal governance from Queen's University, getting a degree. In my childhood, she was the township clerk — and church organist. I'd like to ask her now about resilience, but I know what she would say: it came from God. I hope she would say more, though, than trust in the almighty.

You won't find the almighty in Ballard. And while I find I remain an eternal optimist (why?!) — or at least an idealist (I just expect things to work out, somehow, while also first expecting them to crash into chaos) — I'm also still searching for a foundation upon which to create in a world gone to bits.

I used to write fiction, quite copiously, but I haven't in years.

Grandma, how did you do it?

*

"There is no poetry after Auschwitz." That's how it goes, right? Adorno?

I thought, I will establish Adorno as the extreme case, the outer edge, then I will frame my analysis from there, except that Adorno said no such thing.

The true quotation from Adorno is from his 1949 essay, "Cultural Criticism and Society," and the quotation everyone misremembers is from its conclusion:

The materialistic transparency of culture has not made it more honest, only more vulgar. By relinquishing its own particularity, culture has also relinquished the salt of truth, which once consisted in its opposition to other particularities. To call it to account before a responsibility which it denies is only to confirm cultural pomposity. Neutralized and ready-made, traditional culture has become worthless today. Through an irrevocable process its heritage, hypocritically reclaimed by the Russians, has become expendable to the highest degree, superfluous, trash. And the hucksters of mass culture can point to it with a grin, for they treat it as such. The more total society becomes, the greater the reification of the mind and the more paradoxical its effort to escape reification on its own. Even the most extreme consciousness of doom threatens io degenerate into idle chatter. Cultural criticism finds itself faced with the final stage of the dialectic of culture and barbarism. To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes even the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today. Absolute reification, which presupposed intellectual progress as one of its elements, is now preparing to absorb the mind entirely. Critical intelligence cannot be equal to this challenge as long as it confines itself to self-satisfied contemplation.

The soundbite would be: "To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric."

Not a scholar of Adorno, I read various commentaries online: here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

One summarizes what she calls "Adorno’s dilemma": "only through culture could the horrors of Auschwitz be expressed, but he also finds culture to be an abhorrent, inadequate means of expression."

I thought, okay, this is not the outer edge of my argument; this is my argument. Or at least my question. After catastrophe, how to create? My solution was, the purpose of creation becomes the articulation of that dilemma. Post-catastrophe art is art that articulates its post-catastrophic nature, viz J.G. Ballard. See examples, blah blah blah.

I had worn myself out, previously, wondering how one creates in a world falling apart. To write a story is to assume certain continuities, but if the world is consumed with anxiety about collapse, then what? It seemed to me, eventually, that one needs to create AS IF THE CATASTROPHE HAS ALREADY HAPPENED.

Which it has, right?

Loveless turns to works like Thomas King's The Truth About Stories (2003) and Donna Haraway's The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (2003). An oversimplified summary of King would say, if you want different futures, tell different stories. What Loveless says about Haraway's work interested me more. Her interest is in the cojoined role of artist and researcher, principally in academic settings, thus:

[Haraway] implicitly argues that it is in allowing ourselves to be drawn by our loves ... and examining the complex web of relations that we inherit thereby, that we might inhabit research questions ethnically. ... It is only eros that can fulfill these messy conditions. In other words, when in love-as-eros, the story is never told; it is always in the process of unfolding; and therefor always needs new ways of accounting and rendering accountable. ... True love (eros) leads, as Haraway models for us, to true curiosity (27).

This conclusion or advice (how to create art at the end of the world) is, I know, obscure. Later in the book, Loveless isn't much clearer:

The language of the end of the world, and the denial, deferral, and despair of that language, seems to be everywhere these days. The end of democracy, the end of capitalism, the end of higher education, the end of the planet. Methane, plastic, ocean acidification, melting ice caps. No one knows what will hit next or how quickly things will accelerate (99).

…

The future seems bleak and how to move forward and for whom* -- Cui Bono -- is an open question.

What does she suggest? I'll summarize. Follow your heart. Love all your relations, human, animal, and ecological. Find new ways to tell these stories, via both research in the academy and through art practices. Move incrementally. Move collectively. Stay within the institutions; do not retreat. Engage via eros (deep curiosity, true love).

For the author of a book beginning with the words "How to...", is oddly non-prescriptive, but this is art we are talking about. I recently came across a short essay by Donna Tartt (Harper's, July 2024), reproduced from an introduction to the audio-book edition of J.F. Martel's Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice (2024). From near the end of the piece:

A work of artifice, intent on pushing the audience into a predetermined direction or point of view however well-intentioned, is incapable of suggesting a way forward through a dilemma of any complexity without being preachy and simplistic. But in helping us think with the world, instead of about it, art — which has no agenda other than being itself — always reminds us that all human-created systems are contingent, for if we wade around inside a great work of art, all sorts of rifts appear, ambiguous open spaces of opinion and preconceptions, where light breaks through unpredictably, revealing trapdoors and hidden connections — and even possible escapes.

...

Much of art happens, and has always happened, in the useless spaces between things, in the eerie psychic junkyard that Yeats called "the rag tag boneyard of the heart."

Final words to Loveless:

Research-creation, at its best, has the capacity to impact our social and material conditions, not by offering more facts, differently figured, but by finding ways, through aesthetic encounters and events, to persuade us to care differently (107).

Loveless does not mention Adorno, but her manifesto is a kind of response to him. Poetry is not barbaric after Auschwitz, she might say; it is necessary; if done correctly, it can be a corrective. It makes us deeper in love with life. It is a means of making us think/feel about our many ongoing catastrophes, globally, locally, politically, aesthetically. Art is not activism, but art can be activism adjacent, and it must be ethically grounded. In fact, I remember reading parts of J.P. Sartre's Literature and Existentialism (1949) years ago and stopping at a line, as I remember it: "Nazi art is not possible." Because the complexities that art requires are not possible within the Nazi mind. Interesting the publication date for Sartre is the same as Adorno's.

Fascism and art are incompatible. Still, Adorno's critique of the superficiality of culture is well taken.

Art, deeply engaged, isn't easy.

*

When I was doing my Adorno-related surfing one of the links that popped up was from The New Yorker (January 23, 2011): an article by Ruth Franklin on Adorno and H.G. Adler (1910-1988), a London-based scholar, writer, and Holocaust survivor. Adler was unknown to me.

Franklin makes the case that Adler's career, his novels, memoirs, and poems, offer a corrective to Adorno's absolutism.

In Adorno’s ideologically driven view, no kind of sense could be drawn from the victims’ fate; to try to impose an artistic coherence upon such a monstrosity was an inherent falsification, and to write poetry in its shadow epitomized the decadence of bourgeois culture. For Adler, the attempt to assimilate the horror of the camps into art was a necessity—not only an essential aspect of his life’s work but also a means of recapturing his own humanity after the catastrophe [emphasis added].

Here with Adler (via Franklin), building on Loveless, King, and Haraway, we're starting to get somewhere.

After catastrophe, recapture humanity.

Below, I will be turning to Ballard.

*

But first I need to get in the life bits. What was my 2014?

January that year started with a deep freeze that burst pipes in my basement, just as I was about to fly to the UK. I turned off the water as my in-laws arrived to house-sit and mind the cat (and the kids). I turned over the plumbing problem to my father-in-law and left the country.

I went to the UK to visit with my grandfather's (1915-1994) second wife, Gladys, my step-Nana, whom I'm known my whole life and called by her first name. She continued to live in the house my mother grew up in, Upminster (east London), Essex, last stop on the District Line. My mother's Nana had moved there as WWII broke out (1939), living in an apartment. Her two daughters would soon join her, my Nana and my great-aunt, along with their children while their husbands were away at war. My mother remembers, still, the bomb shelter dug into the yard behind the apartment building and the sound of the German V-bombs overhead.

In 2014, Gladys had been 20 years a widow and remarkably steady, I thought. She was 89 that year. I had last seen her in 2007. My parents had been to see her in late 2013 and were concerned about her, especially her memory. I'd said I was looking forward to playing Scrabble with her, something she enjoyed and was fierce at. My mother said to expect that might not be possible. It was possible. She beat me. In fact, I found her quite capable of managing her day-to-day routine, until events fell outside of that routine. We had arranged to meet with folks at a local store (Roomes) with a nice cafe, very British, and Gladys couldn't hold her in head who we were meeting with or when. I didn't know, since she had made the arrangements. She kept asking me what the plans were. When we meet with the folks, including her niece, I was pulled aside and interrogated how she was doing. Day-to-day, I said, fine; this event, terrible. Within a year, she was examined by professionals and found to have a short-term memory of zero. She was moved (note passive voice) to a home, which she promptly escaped from, then to another home, where she remained, telling folks it was a hotel and that she would be "going home soon." Not so; she would pass away in 2017, having advanced to needing to be constrained. A nurse showed me the paperwork that allowed her to be constrained. She'd been asked if she knew what liberty was and if she felt she had it. (They were about to take it away.) Yes, she said. She knew liberty, and she certainly had it, and she would never give it up. She always did what she wanted, and she always would. Herself, to the end.

I'd left my frozen pipes at home, the deep freeze of Canadian winter, and arrived in a green and pleasant (mostly) land.

Christmas 2013 had been super hard, though, and I'd entered 2014 vowing that it would be a better year. I needed to make changes, I knew. I needed to drink less alcohol. I needed to lose weight, having topped 210 lbs, up 30 from where I had been two years earlier. I needed a gym routine — and generally a better state of mind. "Moving on," is what people expected of me, what I expected of myself, what my late-wife would have wanted for me, everyone said. Why couldn't I do it? I spoke to a friend of mine who'd lost a child, her only, to cancer, and she recommended some grief books and her therapist. I took her up on all of the above. The top book she recommended was Healing Through the Dark Emotions: The Wisdom of Grief, Fear, and Despair (2003) by Miriam Greenspan.

I have recommended it constantly ever since. The therapist, when I met him, asked me what I wanted. That was easy, I said, and also impossible. I want Kate to come back. I want my old life back. I can't imagine wanting anything else. Well, there were some arrangements that I wanted to change with my late-wife's ex-husband, related to shared child management. The schedule, for instance. We can work on that, the therapist said. One step at a time.

My life felt out of control, though in retrospect I struggle to see how. I had a pretty good routine, which was also maybe the problem. I felt bound by it, trapped by it, unable to exert change or implement any flexibility. Because the kids needed that stability. And their father had all the custodial power.

We would learn to make incremental changes. As the therapist said. One step at a time.

Then my younger brother had a heart attack, a minor one, thankfully, but one that sent me to my doctor. My father had had heart attack at age 51; I was 46 in 2014. Heart disease had long been a "known risk." I'd started preemptive statins years earlier. Immediately, my doctor sent me to the cardiologist, who upped my statin dosage. "But my GP just told me my levels were okay?" Not any more, apparently. I'd moved up a risk category. She booked me for a stress test.

But before I had the stress test, I attended "Camp Widow," a kind of conference for spouses of the deceased run by Soaring Spirits International, a California-based grief support organization. I summarized the experience in my "After the End" essay:

this event brought together 120 widowed individuals (110 women, 10 men) and offered a variety of workshops, seminars and peer support opportunities. I wasn’t sure I would like it. I wasn’t sure I would get anything out of it. But I did like it, and I did get a renewed sense of vigor and momentum out of it. Primarily, it helped me realign my heart and my head, accept that I am a widower now, and a widower forever, and understand, perhaps for the first time, that moving on does not require letting go.

I mean, I knew that. I was living that. But this is where the peer support was so important. In my life, I have no peers. I know no one my age who has lost a spouse. People my age tell me things like, “Divorce is like a death.” And they tell me how horrible it was to lose a parent. These events are horrible, and painful, but these people are not my peers. I go to work day after day and try to be a productive person, but my sense of belonging in my life is shattered. Everyone wants me to get “back to normal,” but there is no normal to go back to. If I have a new normal, it will be something I need to build out of the shattered remains of my former life. “Camp Widow” made that crystal clear.

I wrote a longer summary of my Camp Widow experience, saved here.

Then I failed my stress test, the results showing an abnormality. I was booked for an angiogram.

We're now in November. The cardiologist said she didn't expect the angiogram to show much, but boy was she wrong. It showed I had three major blockages in my heart, one 90%, one 70%, one 60%. I would maybe need surgery, I was told, but then I was booked to go to Sunnybrook to have stents inserted. My angiogram was on Monday, take the week off, they said, then go to Sunnybrook on Friday. What do I tell my employer? You'll be back at work next Monday. Another oopsie.

Because at Sunnybrook, they pumped me full of blood thinners, then sent me into the operating room, where the stent guy looked at my heart on two enormous monitors above me, which I could see out of the corner of my eye, though I tried to avoid looking at my 2-foot-wide beating heart. Stent guy asked me how my week had gone. Had I had any heart pain? Sure, I said. Now and then. What were you doing? Nothing, I said. Hmm, he said. Then he told me he would be right back and left. Maybe five minutes later, he returned and said he would not be proceeding, because if he did he would probably give me a heart attack "or two," and I deserved, at least, a chance to speak with the surgeon. I had a catheter stuck in my right wrist, which then followed a blood vessel to my heart. He immediately pulled that out and put a clamp on my wrist. I was wheeled on the stretcher back into the waiting area, where I reunited with my mother. Nothing happened, I told her. We waited for the surgeon, Dr. Fuad Moussa, who would soon tell me I was an easy case. Easy for him, hard for the stent guy. Easy because I was young, healthy (?), lacking secondary complications (e.g., diabetes or other). His specialty was off-pump heart bypass, which meant he operated on beating hearts (didn't stop them and put the body on a heart/lung machine). This was better for recovery and long-term survival.

Okay?

Umm, I said. I don't really have another option, hey?

They sent me to the Intensive Care Unit for the night, because they'd poked my heart already with a catheter, and I was considered unstable. On the verge of a heart attack. Unstable angina. A doctor in the ICU read through my file and told me I was there because I smoked cigarettes. I don't smoke, I said. I mean, I have in the past, sometimes, but not since 2002. Like, what?

They'd pumped me full of blood thinners for the stent procedure, now they couldn't operate until the blood thinners passed through my system. So I would have to hang around the hospital until my body was ready and the surgeons were ready for me. I would not be going back to work on Monday! The surgery would proceed the following Thursday, so I lay in bed and waited. One time, bored, I got up and started pacing in the hall. A nurse quickly shooed me back to bed. "What are you doing!" Walking? Like, I was at home living my life just a few days ago.... I thought I should tell the kids that I might die. This was a big surgery. If something went terribly wrong, I thought it best to warn them. Later, in the school yard, one of the mothers there told me the younger one had come to school on the day of my surgery, saying: "He better not die!" Yes, I better not. I'm glad I didn't lol.

I was first in line for the operating room on that Thursday. They wheeled me in. The surgeon said hello, the anesthetist said to count backwards from 10, then I woke up in the ICU, my parents smiling faces looming over me, everything a blur. Later, I would vomit, terrified my chest would explode. The nurse told me I had a clicker in my hand where I could give myself dose of pain killers. I pressed it constantly. I don't remember any pain. Within hours, it seemed, the nurse had me stand up beside the bed. The day after surgery I moved to the cardiac ward, which was one floor below the cancer ward where my wife had spent a week in April 2012. I had four half-inch tubes protruding from my abdomen, releasing what seemed like gallons of puss. The day after that they gave me a walker and asked me to take a few steps. The day after that, walk a bit more. The day after that, walk a bit more. They brought an x-ray machine into the room and zapped me daily. On the Sunday, a young doctor said he was going to remove the tubes. He grabbed them, said hold your breath, then yanked them out. Don't move for an hour, he said. If you feel any pain, press the button for an emergency.

This can't be right, can it? Going for walks before the tubes were removed? They had me standing very quickly, I know, but the walks must have started after the tube removal. I know for sure, the following Tuesday I was sent home with some nifty pain killers and instructions to walk every day, a little bit more, then the little bit more, and also don't lift anything more than 5 lbs and beware of seat belts across the chest. Don't drive for at least a month. Don't shovel snow.

I headed for my parents' apartment, where I took over their bed for a week and walked up and down the hallway. My back muscles were incredibly sore, and I remember lying in bed wanting to roll over and it took every ounce of energy I possessed. What I had come to.

Within weeks, though, I was walking the neighborhood and preparing meals again for the kids. I didn't go back to work, though, for many months. But that's a 2015 story.

Bottom line: I did not have a heart attack. The pre-emptive triple by-pass gave me, cliche be damned, a whole new lease on life.

Later, I heard about "broken heart syndrome."

I would be remiss if I didn't mention 2014 included the start of a neighborhood book club. I remember lying in the hospital, reading Miriam Toews's All My Puny Sorrows (2014), wherein one character has heart surgery and then dies. My parents knew Miriam's mother. Via church. To this day, my mother gives me updates on what Miriam and her children are up to. (Her daughter now has a second book out?)

In 2014, the essay on J.G. Ballard, grief, and "After the End," appeared online ... before I had my surgery, I think. I completed it in the weeks before, anyway.

And through 2014, The Danforth Review continued.

Issues published that year: 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56.

I published only seven pieces on my blog, The Underground Bookclub:

Shawn Syms - review of Nothing Looks Familiar

Sheila Heti - review of How Should a Person Be?

Michelle Berry - review of Interference

Lisa Moore - review of Caught (first appeared in Canadian Notes and Queries)

Zachariah Wells - review of Career Limiting Moves

The M Word - review of The M Word: Conversations about Motherhood ... I remember this one, because I noted the book has all kinds of mothers (biological, step, CIS, LGBT, aunties), but not male mothers ... also the lost mother. I had received a Mother's Day gift, I noted. There's room for conversation about this label, surely.

I had a personal (non-literary) blog also, which is long gone. The piece on Camp Widow originally appeared there.

My pace of blogging was definitely slowing down. It would come to an end in February 2015, as I would enter then an extended break from scribbling until I started Art/Life in 2021. TDR would continue until 2018 (and remains on hiatus).

In 2015, I made big life changes: new fitness, new diet, new stress balance, etc.; engagement with art atrophied significantly, for a while.

I published one short story in 2014, "The Matter of the Orgasm" (Numero Cinq). The title comes from a random page of Philip Roth's novel, My Life as a Man (1974). The story concerns events that happened in 2002, which provoked me to have more than a few cigarettes. I haven't published any fiction since. I have deeply ambivalent feelings about this story, because is it even a story? I think of it as fiction, but it depicts things that happened. If I were to write it as memoir, it would certainly be framed more generously. It depicts the end of a relationship to a woman I loved and respected. She became ill and retreated to live with her parents. Her father was a massive jerk and made confusing events way worse than they needed to be. I guess when I turn to 2002, I will need to find a way to frame this story as I would prefer it to be told. One of my girlfriend's last words to me were, if you want to write about this you can. I didn't want to write about it then, and I still wish I hadn't in 2014.

This story didn't put me off writing fiction. I don't want to imply that. It's just that the shift to autobiography in fiction, via this story, was new. There are real-life elements in my earlier fiction, but they are well obscured. I told fact slant, sure, but also significantly distorted them. I was turning in 2014 away from that approach, pulled more and more into telling it straight. I was trying to write fiction, and all of the narratives would introduced a dead wife struck down by cancer. I didn't want to encounter that in fiction. I didn't want to work through that in fiction. I wanted to find a way around that. I wanted to write about catastrophe via metaphor, not via memoir.

This Art/Life project remains at attempt to sort that balance.

J.G. Ballard would also help me open some of those closed doors, I thought. I was soon seeking out his work, as much as I could.

*

In "After the End," I summarized four Ballard novels, as follows:

Concrete Island (1973) is a retelling of Robinson Crusoe, except the island is a traffic island lost in a sea of traffic lanes and overpasses. It’s a slim book, and if I wasn’t specifically interested in Ballard I don’t think I would have picked it up, but it gripped me. A middle-aged man on his way home from a rendez vous with his mistress goes over the barrier in his fancy car, rolls down a hill and is trapped in an odd parallel universe, which is within reality and also outside of it. He discovers the island has other denizens, a self-supporting ecosystem, and no way to escape. His expectations of life are fundamentally and suddenly altered, and he must adjust, or die. I identified with that.

The Day of Creation (1987) is also an “after the end” novel. The action takes place in Central Africa, a parched and desert-like place. An Englishman, Doctor Mallory, goes on a Heart of Darkness-type quest after a mysterious river is suddenly sprung free from the earth. In a chaotic world, ruled by paramilitaries, bureaucrats and a freelance television crew, Mallory brakes free and leads all and sundry upriver, seeking its source. There’s some high adventure in this one, but also lots about a world under stress from capitalism, militarism, technological expansion and, let’s just say it, men. The mystery of the natural world is set against all of this. The power of women and girls, too. The new great river. The land mass of the African continent. A wild, post-pubescent, silent girl, who enters carrying a gun, and is equally terrifying and heartbreaking. The novel quickly reveals the foolhardiness of those who think they “know” anything about anything. Propelled backwards into the future, we go. Fuck ya.

Super-Cannes (2000) takes us into a world of ultra-capitalism and a different kind of desert, a kind of intentional community, though it is built for Forbes 500 companies, not 1960s back of the landers. It is also a post-catastrophe novel, in this case a murder rampage which had disturbed the perfectly controlled, micro-managed village just before the arrival of the protagonists, a husband and wife. She is the new doctor (replacing the doctor turned mass murderer), and her husband is the narrator, who has a lot of free time to investigate the goings on of his new surroundings. The genre explored here is whodunit? Or more precisely, whydunit? The plot thickens and thickens, as our hero is introduced to the reigning psychiatrist, who explains the theory and practice of the super village. It is designed to take care of its residents’ every need, so that they can be as productive as possible, and rake in the dough for the multinationals who are paying all of the bills. Taking care of everyone’s needs leads to an unexpected result. Folks are bored. All work and no play, it turns out, isn’t healthy, and the dark side of the soul needs to be exercised. So the folks organize under-the-cover-of-darkness vandalism brigades. Plus much more. I didn’t identify with the plot here, not in a “post-grief” way. But the undercurrent of swirling chaos felt very real. It made me think of the cancer period. It made me think of the dark truths hidden by systems.

Millennium People (2003) continues down this path. The action is set in contemporary England. A bomb has gone off at Heathrow, in the arrivals luggage area. The protagonist is a senior psychologist and his ex-wife is among those killed by the bomb. Through his job, he becomes involved in the investigation, but he begins his own independent research as well, getting drawn deeper and deeper into a shadowy world of domestic terrorism and anti-capitalist rebellion. The book contains an enlarged critique of big money and the faux surface “realities” of consumer culture and mass media. As with Super-Cannes, the plot plays with the idea that violence leads to a truer engagement with life, an idea that Ballard has returned to for decades. See, for example, Crash (1973), where characters stage car accidents for sexual pleasure. I found Millennium People to be the least satisfying of the four Ballard novels I read in this sequence. Some of the ideas felt recycled. The protagonists were starting to blur together. But the insights about an outer shell of mass media images obscuring and inner crust of essential “being” expressed what I felt to be intuitively true in my post-grief blurriness.

Recently, I have been more drawn to Ballard's non-fiction. I've started to make my way through A User's Guide to the Millennium (1996). I also have a copy of Ballard's Selected Nonfiction 1962-2007 (2023), edited by Mark Blacklock. Initial forays into both collections led me to a simple conclusion: this is how an adult writes. Serious but with humour, fearless, clear, exploding with ideas. In a word (two words), sharply alive.

For example, Ballard's essay "Hobbits in Space?" is a hilarious and insightful takedown of Star Wars (1976):

I firmly believe that science fiction is the true literature of the twentieth century, and probably the last literary form to exist before the death of the written word and the domination of the visual image. S-f has been one of the few forms of modern fiction explicitly concerned with change — social, technological and environmental — and certainly the only fiction to invent society's myths, dreams and utopias. Why, then, has it translated so uneasily into the cinema?

What Ballard finds missing from Star Wars is "any hard imaginative core." The saloon scenes he finds "hilariously like the Muppet Show," saying he expects "Kermit and Miss Piggy to swoop in."

Later, in a 1993 piece, also on film, he writes:

Fortunes are now spent on the kind of computerized special effects that appeal to the Super Nintendo mind-set of the present-day twelve-year-old, for whom adult relationships, political beliefs and the bitter-sweet ambiguities of love and loyalty — the magical stuff of Casablanca — are as remote and boring as the kabuki theatre.

Ballard would not be surprised that 30+ years later, movies are being made that are adaptations of video games. They also, more than ever, resemble video games (hello John Wick), and adult-centric films (complex, ambiguous, sexual) are rarer still.

In a review of a book on the history of screenwriting, Ballard asserts:

***

The most interesting films of today — Blue Velvet, The Hitcher and the 30-second ads for call-girls on New York's Channel J (some of the most poignant mini-dramas ever made, filmed in a weird and glaucous blue, featuring a woman, a bed, and an invitation to lust) -- are a rush of pure sensation. Blue Velvet, like Psycho, follows the trajectory of the drug trip. Paranoia rules, and motiveless crimes and behavior ring true in a way that leaves a traditionally constructed movie with its well-crafted plot, characters and story looking not merely old-fashioned but untrue.

There's a lot here that suggests barbarism (qua Adorno) — and a framing around what is true and real (not what we are told is true and real). Ballard throughout his art creation, does away with received wisdom and much established decorum. But he is not nihilistic; he does not claim meaning is impossible, only one must be adult-like in awareness. After the catastrophe, innocence and denial is what's impossible, not poetry. As in The Matrix (1999), one is now awake. One's sense of what is real is narrowly focused, often centring on the body; the senses are what is immediate and easiest to distinguish. Beyond the self, one must sort the simulacrum: advertising, politics, entertainment ... all seeking to stimulate our endorphins.

What I see most in Ballard, the post-catastrophe artist, is the role of witness. Having walked through fire, a new burning vision emerges. The "traditionally constructed" is vaporized. How to communicate (and love) what's left?

On that note, let's consider again the original proposition. Does catastrophe lead to suffering or insight? Is "after the end" a creative ecology or a destitute one? Is Adorno right? Or does poetry have a (non-barbaric) place in the post-apocalypse?

Well, you know me, I don't like binaries. None of these questions are either/or; they are both/and.

Catastrophe leads to suffering, no question. And poetry is possible (and not barbaric (merely)) after earth-shaking disaster. Yes, too, there is insight to awakening to a world "after the end," a position for renewal and new beginning, creation infused with deep life, true love, curiosity, sustainable in new ways. Art is possible here; it is not wasteland.

Does J.G. Ballard provide a unique example in that regard? He's unique, that's for sure, but I can't promote him as providing a singular, prescriptive approach. He has a singular vision, sure, but he's not the only one, and his way is not the only way. The path is open to anyone, and everyone.

Go.

I'm curious to see what you do with it.

*

CODA

I thought I'd stick this story at the end. When I was in the process of being discharged from hospital, following heart surgery, the charge nurse, a youngish man with a heavy Quebecois accent, told me I was very lucky "because the doctors couldn't agree what to do with you."

"I got that," I said. The stent guy had referred me to the surgeon.

"I was so pleased when I read that in your file," he said. "I love it when my colleagues demonstrate medical ethics."

"What?" (Isn't that their job?)

He said, "That guy didn't get paid. He had you on the table, and he sent you away, and he didn't get paid. He did the right thing."

"He sure did."

"It's almost like you had a guardian angel watching over you."

I said, "I did, and I do, and I know who she is."

I told him about my late-wife, a former patient of this same hospital.

I choked up. He started crying, I started crying.

He told me the surgeon had given me the "gold standard," and I should go and live a long life.

"Thank you," I said. "I intend to."

CODA TO THE CODA

I realized there is an assumption behind much of this that I haven't stated, at least not directly, which is that I have been a parent (mother?) to motherless children. The day she died, their mother, in the minutes after the moment she died, a moment attended by immediate family, including the kids, one of the palliative doctors said to me about the kids: "They will return to this moment in 20 years."

Fuck, me, I thought. Twenty years. Here we are now, in this moment. THE MOMENT.

After that moment, is "after the end." The kids were then 8 and 12. The whole rest of their lives will be after the end.

In the first years, folks would ask me how they were doing. Excellent, really. But now that they are 20 and 24 the facts of their loss, the weight of their loss, the specificity of their loss is becoming clearer to them. It's not 20 years yet (will be 13 in May).

They are my greatest joy and obligation. How to write again after this loss? Irrelevant.

How to launch these kids into their lives? Everything.

A massive, very thoughtful, honest piece of writing, Michael. I was thoroughly engaged. Glad you wrote it. Lots to think about -- and feel.

Thank you so much for this Michael. Grief is a life long journey. I carry a Grief stone in my pocket. I'm going to buy Miriam's book.