From the beginning of this pandemic, back in March 2020, I've had a sense of deja vu. Not that I was repeating the 1918 flu, but that I had been here before: in an environment of uncertainty, risk, evolving circumstances. The situation was different, but the mitigation familiar: focus on what you know, take it one day at a time, practice mindfulness, remember to have fun.

Of course, we all thought the mitigation would be over by now, which just becomes part of the uncertainty. When does it end? Does it ever end? Accept that as unknown, focus on the here and now.

From late 2010-early 2012, this was how I lived with my wife, who had been diagnosed with breast cancer. "Isn't cancer just another word for death?" I asked myself early on. No, it's not necessary to go there, not until you need to go there. Unfortunately, we needed to go there, and even then we discovered how fully you can live even as you openly accept the end is imminent.

I had the same conversation with colleagues and friends after COVID entered our lives. Yes, it's frightening. No, don't panic. I cited Jon Kabat-Zinn's Full Catastrophe Living. Live mindfully. Remember to breathe. By early 2012, Zinn's recommendations about how to live with catastrophe had become our day-to-day. In some ways, it remains part of my day-to-day and probably will forever.

In late 2021, I tried to write something that would explain all of this. I wrote a good chunk, but then I just stopped. I have alternating waves of emotion and energy. It's good to write this out, I feel, and then, later, this is really painful.

Here is that fragment.

*

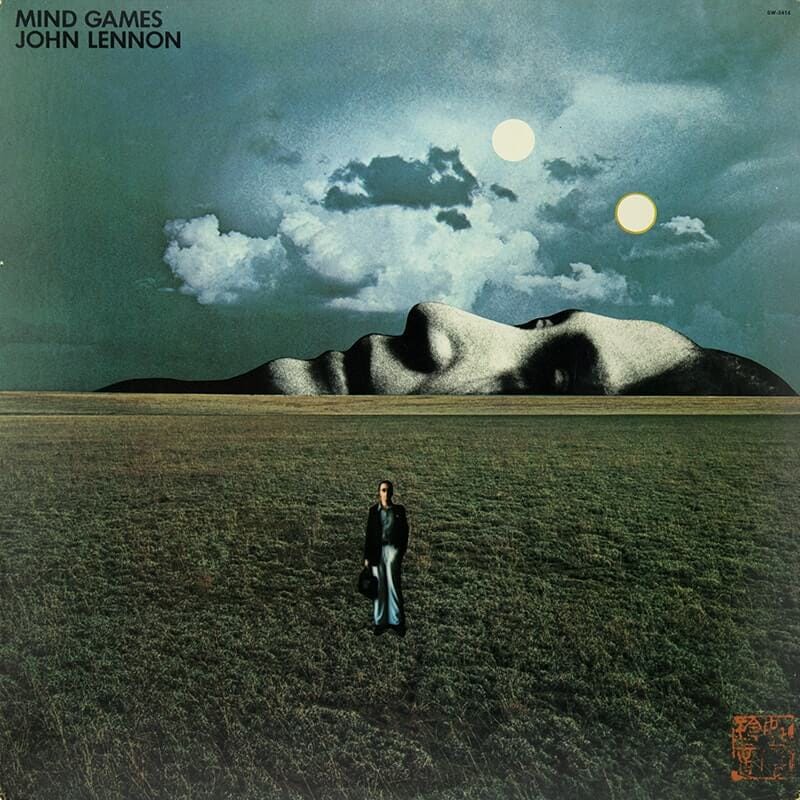

Where to begin? Any place, really, surely, of course. We’ll get around to it all eventually. Nothing escapes. It’s all connected, somehow, somewhere in the back, below, in the root systems, in the fertile earth. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. We return to where we’ve been. We never really get anywhere else. It all happened here, and here is everywhere. Wherever you are, John Lennon sang, you are here. Did he sing that? He had that “You are here” t-shirt. Was there a song too? (Looks it up.) “You Are Here” (1973). From the album Mind Games. Mind games, huh?

As I write this, we are at the start of the second winter of COVID-19. We are tired, confused, eager for the return of so-called normal. It is more a mental struggle, an emotional struggle, than a physical one, though the deaths are real and the suffering is real and it is the vulnerable who are most vulnerable, as it always is, as they always are. COVID is a "C" word like that other "C" word that grinds you down with mind games. The crab, cancer. As the COVID curtain came down in March 2020 and we all started working from home (okay, not all of us, just the ones who could, the lucky ones), we asked ourselves, "How are you doing? How are you adjusting?"

Such a weird moment in time! How will we explain it to others who were not there? How will we remember the past that is gone, the routines and assumptions about routines that have been broken forever? “How are you doing? How are you adjusting?” My answer was, “This reminds me of the cancer time. Living with a new uncertainty, surrounded by potentially catastrophic risk, the destruction of what we used to call ‘normal,’ its replacement with what?” The day-to-day, I told people. “This is what we learned from cancer, how to focus on the essential, how to let go of everything else, how to live in the moment and not worry about tomorrow.” “What we learned,” I said, but there is no “we.” There is only me.

Because I did not have cancer. I lived with cancer. Cancer was in my house. Cancer was in my wife. I was not the victim of cancer, but I was the victim of cancer in my house, cancer in my wife, cancer in my life, and though cancer took my wife nearly ten years ago, cancer remains in my life, the routines of cancer, the so-called learnings of cancer persist. Mindfulness, I told people at the beginning of the pandemic. That’s how you survive the imposition of pervasive uncertainty. That’s how you retain your focus on the day-to-day. It helps, I assured them. I still believe that. It may be the only thing that helps. One of the only things. One of the most powerful things.

We’re as far into the pandemic now as we got with cancer. Then Kate died. The cancer died, too, her brother noted. The diseased cells died, that’s a fact, but the shifts cancer made in our world remained. “We’re not going to let this change us,” Kate vowed after receiving her diagnosis in 2010. We were recently married. Had just passed our third anniversary. We shared two children, aged six and ten, with her ex-husband. We had important things to do. We had big plans for our lives. Nothing was going to be allowed change them, certainly not a disease. We were hard ass on this point and kept at it right to the end.

My mother gifted us tickets to a Yoyo Ma concert in June 2012. As Kate lay on her death bed in late May, my mother asked me what she should do with the tickets. I thought, “Don’t ask me this. Why are you asking me this?” Kate overheard my mother and before I could answer rose up and said, “I’m going!” My mother said she would change the tickets to wheelchair access. Kate died days later. I didn’t attend the concert. I buried this memory for a long time, and when it surfaced I thought, “Holy shit. Kate held on right to the end.” But I knew that. But now I had a story to prove it. What does it mean to live? This is what it means. Live.

Random note. Happiness is overrated, pleasure is not.

With the pandemic came lockdowns. The options for life dramatically shrank for everyone, for the collective good. This is where the analogy with cancer breaks down. Cancer is isolating. It is lonely, despite being an experience widely shared. Cancer happens to the individual. The cancer mind games extend to everyone around them. COVID happens to the individual, too, but the pandemic happened to everyone, everywhere, suddenly. Personal health versus public health, the distinction between the two the source of confusion and conflict. COVID required everyone, everywhere, to change their lives, immediately. Not even cancer did that. Initially, there was no change. Kate’s daughter, aged six, said, “I don’t believe Mummy is sick. She doesn’t even say ouch.” Then the chemotherapy started. Then Kate lost her hair. Then the kids thought she was sick, but it wasn't the cancer changing things. It was the intervention.

In 2020, right when the pandemic started, two of my friends told me their wives had been diagnosed with breast cancer. Around the same time, one of my mother’s friends had her breast cancer return, and a friend I only see through social media tweeted about new breast cancer treatments. There was a fifth woman at this time, I think, a friend of a friend, maybe, but the specifics allude me. My friends with the wives both said the same thing: “I didn’t want to tell you, but ….” But what? “But do you have any advice?” Do I have advice? Oh, yes, I have advice. The first piece of advice is ninety per cent of the advice, and it’s simple, so simple. Don’t go there. If you or someone you love has recently been diagnosed with cancer, you will know what this means. “And the angels of the Lord appeared and said, ‘Be not afraid.’” Isn’t cancer just another word for death? I wondered, after Kate’s diagnosis. No, it is not. Don’t go there. Stay in the moment. Know what you know, and don’t go beyond that. If you need to go there, later, then you will go there. If you don’t need to go there, then keep it simple, stay focused. Don’t.

Easier said than done, hey, I know. That’s why it’s ninety per cent of all you need to do. The rest is be organized and make memories. Always have a note taker at each visit to the doctor. Maintain a notebook, so you can refer to the notes after the meeting. Remember that the meeting with the doctor is your meeting. YOUR MEETING. Don’t leave the meeting until you’ve asked all of your questions. Go into each meeting with a purpose. Know what you want to get out of it. Know what questions you want to ask. Write them down and keep them in front of you during the meeting. Ask what the next steps are, but not what the next steps are after the next steps. Remember: Don’t go there. Stay in the day-to-day.

When I told me GP my wife had cancer, he said, “You will find the hardest thing is waiting.” It was true that there was a lot of waiting, but it wasn’t the hardest thing. On the longest day, we had an appointment with the specialist for early afternoon. We arrived mid-morning for bloodwork. We saw the specialist after eight o’clock at night. The clinic was short a doctor that day, and they were seeing all of his patients, too. Some of the other patients were irate. Kate was gracious. “Thank you for seeing me,” she told the clinic nurse when her name was finally called. I called this the longest day, and it was a long, long day, but the longest day in fact may have been the last visit we made to the hospital. We left home at seven in the morning and returned home at seven in the evening.

It was a Friday, a brilliant warm, blue, sunny day in late May. There was no visit to the clinic that day, only an early morning ultrasound of her head (was the cancer there, too, now?), morning bloodwork, and afternoon chemotherapy. What’s important to note here is that chemotherapy is considered a life-saving treatment. Medically speaking, Kate was not dying, she was not palliative, but she was dying and we knew it. That afternoon, as we sat, waiting, the chemotherapy not started yet, the results of the bloodwork not available yet, Kate’s specialist visited us in the waiting room to ensure that we knew that the end was near. She didn’t want us to be harbouring illusions. We weren’t harbouring illusions. Days earlier, the specialist had asked Kate if she wanted chemotherapy. “I can’t say it will do anything, but it might give you a little bit more time, sometimes people get a ‘chemo bounce.’” Without hesitation, Kate said yes. And so we made our way to the hospital that day, five days before she died.

*

The fragment ends here. I wrote more, but it was all in my head. My memories of those days, the last weeks of Kate's life and still so vivid, and I still return there frequently. Too frequently, sure, which is evidence of trauma, I know. Which is probably why I have impulses to write it all out, get it out of me, and then counter impulses to stop! Don't go there! But there is no stopping it, not in my memories. For me, the catastrophe is in the past, not in the anticipated future, but the mitigation remains the same. Stay in the present. Live.

Whenever Kate and I visited a specialist, we were asked: Do you have any questions? Yes, we would say. What do you expect to happen next? How is this going to play out? Always, and I mean always, right to the end, the doctor would say: We don't know. Frustrating, huh? The doctors would offer probabilities and statistics, but we would decline. We would rather not know the odds, just focus on life in the moment.

These days, I continue to see in the news, on my TV, people clamoring for certainty: When will this be over? Just tell us!

No one knows, folks. Remember to breathe.