It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. 1983. And it was the year I read Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859), too, I'm pretty sure. It was only as I was nearing completion of this piece that I realized it's a kind of sequel to my January 2022 essay on "Cancer, COVID, and Uncertainty." I had thought I was writing reflections on silliness, but what is silliness if not destabilizing — or a recognition of the destabilized? For literary silliness, I include everything from the comic to the satirical to the absurd. For me, 1983 was a destabilizing year, a transitional year, for a host of reasons I will soon get to below.

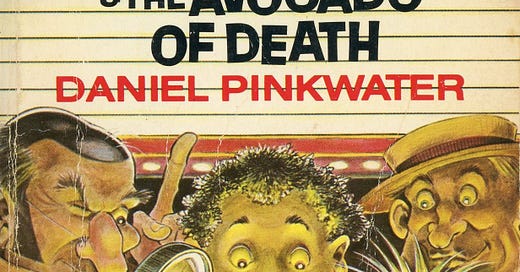

Forty years ago next spring, I read a book I have kept on my shelves ever since, Daniel Pinkwater's The Snarkout Boys and the Avacado of Death (1983). That it was written by Daniel Pinkwater I've only recently rediscovered. The title, however, I've never forgotten. I was sure that I'd read this book in grade six, but it was published in the paperback edition I have in 1983, when I was finishing grade nine. I wrote a book review about it for English class, and one of my teacher's comments was: "Is this book real?"

Yessir. Or maybe, no sir, it's surreal. What's the plot? Honestly, I don't remember. What I remember is the feeling it gave me. Sheer giddiness. Pure silliness. Outright fun. I Googled it to see if it had an internet life. Yes, it's out there. It has other superfans, including those who remember the plot, some of which wouldn't pass the cultural filters today, and rightly so. A certain antisemitic character, one critic said, for instance. Smoking teenagers in a YA book? Must be the 1980s.

The internet tells me that Pinkwater (1941- ) has had an extended career writing for young audiences. A summary of the plot of Snarkout Boys from Goodreads: "Walter and Winston set out to rescue the inventor of the Alligatron, a computer developed from an avocado which is the world's last defense against the space-realtors."

In spring 1983, I was 14. About to graduate from junior high, I had a lot going on. I was the captain of my hockey team, and that was the only year my team won the East York House League Championship. My coach named me MVP, even though I missed the championship game because my mother took me and my brother to England. March Break? We arrived just as my grandmother's second husband, much older than her, died. They lived in Hastings, and my brother and I stayed in Essex with my grandfather, while my mother attended to Nana.

There's some blurry memories here because we also visited England in 1985 and we all went to Hastings then, and my Nana was very much not well emotionally, though I didn't know how much at the time. Years later my mother would tell me that she was afraid that her mother would harm us in our sleep. I remember I slept on the floor in the living room. My brother and I bought a soccer ball and spent hours kicking it back and forth in the park or trying to catch glimpses of bare-chested girls on the beach. Ou-la-la.

Later my mother would need to arrange an intervention for Nana across the Atlantic. My grandparents had divorced in the 1950s. The last time I saw Nana was in 1989. She was living in a rest house beside the ocean, still in Hastings. I was wearing a t-shirt from a concert by The Who. She said, "They're a band, aren't they?" Yes. She'd seemed far away, and the alertness of this question surprised me. After my Nana entered that rest home, she never left it, stopped going outside.

When I returned to London on that 1989 visit, back to my grandfather's place, he asked me how she was. I shrugged and said, "Okay, I guess." She'd had a hard life, he said. This I had known, at least parts of, like the biggest part. Her father, Thomas, had committed suicide, sticking his head in a gas oven when my Nana was only 10, her older sister, 12. The girls had found him. Subsequently, my great-grandmother kept her older child at home and placed my Nana in an orphanage, being unable to afford two girls, though they were later reunited. I have heard my mother say numerous times that after this, her mother was never the same.

A couple of years ago I learned Thomas had been a soldier in World War One. He was in the Royal Engineers, and he'd been at Ypres, where the Germans used poisoned gas. He'd been gassed, hit with shrapnel, and found unconscious in a trench. He was evacuated to England and was never whole again. I learned this from his military file, which I ordered online. A lot of his file is him pleading for a proper pension and doctors' notes saying he's unfit for duty. His expectations of (a certain standard of) life had fallen apart. The lives of his daughters and the instigation of the multi-generational trauma of suicide would soon follow.

In spring 1983, we took a hydrofoil out of Dover to Belgium. My paternal uncle John was working for the Canadian delegation to NATO in Brussels. We visited his growing family. I had three young cousins to connect with there, all boys, aged 7, 5 and 3 that year. We went to Bruges and Waterloo. On television was an advertisement for butter featuring bare-chested women. (I mentioned this commercial to one of my cousins earlier this year and he said, "Yeah, I remember that. It was on for years and years.") My mother advised my uncle that his mother wasn't well, and he said he would visit in the summer. But he came home sooner than that, because my paternal grandmother died in May, a loss so enormous it ripples to this day.

The Snarkout Boys, did I like them because they were outrageous? Absurd? Wild and adventurous? Silly? All of the above? In retrospect, it's easy to see the influence of, say, Kurt Vonnegut. Also, boys being wack: Abbott & Costello, Laurel & Hardy, the Marx Brothers, Bill & Ted. Influence back to Vaudeville, back to Shakespeare, the fool, Sir John Falstaff. Also, more contemporary: Monty Python, the Royal Canadian Air Farce (whom we saw perform live once at the CBC radio studio in Cabbagetown), Jacob Two-Two, Wayne & Shuster, SCTV. After school TV: Gilligan's Island, F Troop, Hogan's Heros, M*A*S*H. The Muppet Show. Gordon Korman's This Can’t Be Happening at Macdonald Hall (1978), which was published when the author was just 14 (and I was 10). The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979). Sue Townsend's Adrian Mole (1982). Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964). The Farley Mowat of The Dog Who Wouldn't Be (1957). Weird Al's parody hits and Sunday night radio with Dr. Demento. In our house, we had influences on LP that were distinctly British: Flanders & Swann, and the stand alone — Goon Show. Spike Milligan, Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe. I once saw my father, wearing a Fire Station Red onesie, recite/perform to an audience the entirety of The Cremation of Sam McGee (1907) by Robert W. Service. The Goon Show and Flanders & Swann LPs were my father's, brought back from his early 1960s years in England. He loved the silly and the bizarre (as do I). At his church, my father started the first (the only?) "Non-Singing Choir." They had their first performance on April 1, 1999. He sent a tape of the performance to the National Library & Archives Canada. On our 1985 U.K. trip, I scoured book shops seeking my own Goon-inspired wit, the early books of one John Lennon.

"Is this book real?" Surely not. What is real anyway? Lot's of things, right?

In the spring of 1983, the St. Clair-O'Connor Community opened. A multi-generational residence with a small nursing home attached, located on the corner of (you guessed it) St. Clair and O'Connor in East York, the building had been the Paul Willison car lot. Willison was known as the dealer with the girl on a swing on his billboard sign ...

My parents had been involved in getting the residence built, as it was a joint project of two east end Mennonite churches. After the car lot had been sold, a group of us went into the building with hammer and bashed out walls, starting the demolition. The day of the opening, I sat with my friends in the back of the building, watching the ceremony of speakers. Later in the 1980s, I would be a weekend janitor. I also went into the offices three days a week to empty the garbage and clean the toilets.

When I consider spring 1983 now, I think what a list of events: We visited England and Belgium, my Nana's second husband died, my grandma died, my hockey team won the championship without me, but still named me MVP, SCOC opened, I graduated from grade nine and matured out of junior high. I was 14, turning 15. One more thing happened at school. Well, two. I had loved my art class, and if you'd asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would have said, an artist. My paternal grandfather was a graphic designer. I thought this was a path for me, but my grade nine art teacher told my mother at a parent-teacher interview that I should consider a different path. Being an artist was really hard, not a path he would encourage. I remember the devastation of this comment. His class was my favourite class. Making art gave me the greatest pleasure. But even though I continued to take art classes in high school, my commitment to it was never the same.

Easy to write that, but is it true? This Substack is called ART/LIFE, after all. The art has always been there. I'm still trying to find ways to access it. I still loved art classes in high school, but as I approached graduation I didn't see a way to continue it, the painting, sketching, sculpting. I started to think what else can I do that involves creativity, if not what I thought of as art. How about writing? In retrospect, what surprises me is how art seemed disconnected from the world then, while writing seemed deeply integrated into it. Writing, even the silliness of the Snarkout Boys, seemed a gateway to knowledge, while art seemed a gateway to escape. Clearly this is an incorrect and naïve view, but I didn't figure that out soon enough.

Anyway, the second thing that happened at school at the end of grade nine was the graduation ceremony, where I was surprised to discover that I won the boys' "general proficiency" trophy — for the highest overall mark by a graduating boy. I think there were maybe three girls ahead of me, overall, but, you know — it was the peak of my academic career. Though that ground on another dozen years or so. I also won the "geography" award, a subject I never took again, even though many of the topics that continue to fascinate me could easily fall under that rubric, from urban planning to various analyses of people and places.

For example, a note on carbon dioxide. I'm currently reading Rebecca Solnit's excellent Orwell's Roses (2021), an engagement with George Orwell and his work through the filter of the rose plants Orwell planted at his rented country hovel in 1936. Solnit visits the Hertfordshire cottage and finds roses. The same ones Orwell planted? Quite possibly. Her essayistic voice ranges widely. Among other things, she notes:

In 1936 [atmospheric carbon] was at only 310 parts per million, well within the limits to maintain the climate of this Holocene interglacial. Even in 1984, those levels were just below the 350 ppm settled upon by climate scientist James Hansen as the upper limit for a stable Earth. Orwell's final novel looked forward to 1984 as a year deep into political horror. We can look back across the huge divide that is our terrible knowledge and our worse actions to 1984 as the last good year, in terms of climate.

Solnit also writes about art as escape, art as beauty, beauty contrasted with politics/activism. Most readers of Orwell would prioritize his politics, which Solnit also keenly analyzes, but she prioritizes the roses, symbols of beauty, sure, but also actual roses, a true and real perpetual engagement with the earth and its cycles of life. She notes Orwell's commitment to both politics and what even he struggles to call aesthetics. Orwell is deeply committed to life's simple pleasures, often highlighted in his essays and a key theme in Nineteen Eighty Four (1949), one often overlooked by anti-authoritarian readings.

It's interesting that the beauty/politics dichotomy came up here. I see a parallel to the ART/LIFE theme I've been exploring all year. In the first piece here (January 9, 2022), I wrote:

Back in the day, when I was a teenager in the 1980s, I thought I had to privilege one or the other. And if I had to choose, I would have chosen Art. "I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the heart’s affections and the truth of the imagination." — John Keats. Like Keats, I felt certain the imagination led to otherwise unknowable truths.

Yes, I wanted art to be an escape. Why did I want to escape, though? Maybe I had some sense of an underlying crisis I wanted to avoid. Maybe the events of 1983 were the crack that, as Leonard Cohen says, let the light in. Maybe also, it was just the 1980s. "You don't have to live your life in a state of perpetual crisis," is something I've said to my step-kids. Their mother died 10 years ago, when they were young. They've known more instability in their young lives that I ever did at their ages. I don't need to tell them that things don't always work out, or that one's expectations are often thwarted. I tell them what their mother would have told them, that life is beautiful, even in the midst of uncertainty. I think now silliness, and all that comes with it, is more than a coping mechanism. It's the string that binds together the disparate, the links in the web of connections, often odd, often comic.

In conclusion, I'm going to make one final turn here, towards a consideration of literature in the context of Snarkout silliness. Has there been a lasting legacy? Does it represent a reading theme? Northop Frye would categorize it within comedy or satire, surely. I remember Lynn Coady commenting once that the only writer allowed to be funny in Canada was Mordecai Richler. It's not quite as bad as that, but it's close. Canlit and comedy don't overlap much, or not often enough. American comedy is overrun with Canadian comedians and comic actors, but Canlit trends earnest — and commentary about Canlit trends sociological. Geographic?

Still, Miriam Toews persists in a comic approach. Lynn Coady has done her part. Jessica Grant's Come Thou, Tortoise (2009) has lovely whimsy. Jane Siberry's "Everything Reminds Me of My Dog" (1989): ditto. We could use more novels like Russell Smith's How Insensitive (2002). Andrew Kaufman's All My Friends Are Superheros (2003): just great. John Lavery’s verbal play and comic take in You, Kwaznievski, You Piss Me Off (2004) is sublime. I love the comic takes, and complicated seriousness, in the work of Douglas Glover and Mark Anthony Jarman. Leon Rooke is a category unto himself. So it Stuart Ross. Must mention: Gary Barwin, Yiddish for Pirates (2016). Thomas King's One Good Story, That One (1993): classic. Zsuzsi Gartner’s Better Living Through Plastic Explosives (2011) is apparently polarizing, but I love it. Darwin’s Bastards (2010), the anthology Gartner curated of the weird and wonder is, well, weird and wonderful. As is Peter Darbyshire’s The Warhol Gang (2010), Spencer Gordon’s Cosmo (2012), and Carrie Snyder’s Hair Hat (2004).

I'm also curious about the 2022 anthology, After Realism: 24 Stories for the 21st Century (editor André Forget), which suggests "the short stories in this ground-breaking book are an essential starting point for anyone interested in daring alternatives to the realist tradition that dominated 20th century English-language fiction." Though it’s not like we haven’t been here before, trying to break Canlit from it’s realism addiction. See, for example, Ground Works: Avant-Garde for Thee (2003), Christian Bök, editor; introduction by Margaret Atwood. Also, Noman’s Land (1985) by Gwendolyn MacEwen.

Richler? Of course. Even when he was bad, he was good. Is that still true? Hmm. Will have to check.

A bit off track here, but folks may also want to revisit the 2008 Salon des Refuses brouhaha about the state of short stories in Canada. See also Nigel Beale’s take on it all.

Some non-Canadians with a comic/whimsical, sometimes demented, bent.... Flann O'Brien, of course. At Swim-Two-Birds (1939) and The Third Policeman (1967). The early manic Amis. P.J. O'Rourke's 1980s work for Rolling Stone, particularly his account of visits to Belfast and Soweto. Brautigan. Vonnegut, again. Bartheme. Pynchon, sure. Amy Hempel. Aimee Bender. Deborah Eisenberg. George Saunders. Terry Southern. Joseph Heller. Sam Lipsyte. Barry Hannah. Patricia Lockwood. Terry Gilliam's "Time Bandits" (1981), which I saw numerous times as a 13-year-old and loved it, then saw it later on TV and couldn't believe how dark it was. Which is maybe a good point to end on.

The world can be so incredibly dark. Comedy breaks it down. I recently binge-wanted all eight seasons of Game of Thrones, and what a mess of chaos that was. One thing about that world became starkly clear, there is no art, there is precious little contemplation. The production has elements of comedy, but within the world itself there is little laughter, and pleasure choices are framed as either sentimental connection or debauchery. Competition for power is all. It is a sad Hobbesian world full of rape, homicide, and genocide, desperate in need of escape — the rise of artists and a new style of storytelling. Snarkout 101.

Great read. Nice list of sublimely silly works. A topic so little thought of. Your father reciting Sam McGee is the best. Thanks.