I was going to start this by saying the 1984-85 Toronto Maple Leafs set the standard for futility in a franchise long down for disappointments, but then I started to watch the 2021-22 NHL Playoffs. Over and over commentators noted that the Leafs have not won a playoff series since 2004—18 years ago. That is a franchise record. And I see between 2005-06 and 2015-16, the Leafs missed the playoffs 10 out of 11 opportunities.

Ah, in the 1980s we used to say we were long suffering Leafs fans. They haven't won the Stanley Cup since 1967! Growing up, I knew people not much older than me who retained some of the entitlement of Leafs fans of the 1960s. They remembered multiple Stanley Cups. They had a sense of ownership for the Cup. It was ours, it must return. It had been, gosh, nearly 20 years! LOL. Now it's 55 years.

Still, the 1984-85 campaign was the worst ever. The team ended with 48 points, coming from 20 wins, 52 losses, and 8 ties. As a reward, they selected Kelvington, Saskatchewan's finest, Wendel Clark first overall in the 1985 draft. I took notice. Things were looking up. The following Christmas, I bought a Leafs jersey, #17, soon my favorite attire. I held onto it until a couple of years ago, when I decided to replace it. My new #17 includes the "C", noting the Captain Clark later became.

No, there was no Stanley Cup in Clark's future, but his team went to the final 4 twice, which is the best any Leafs team has done since, yes, 1967. The current team is plenty talented, and they racked up the most points (115) ever in Leafs history for a regular season (54 wins, 21 losses, 7 ties, almost perfectly reversing the W-L ratio of 1984-85). But they've won nothing yet, not one playoff round.

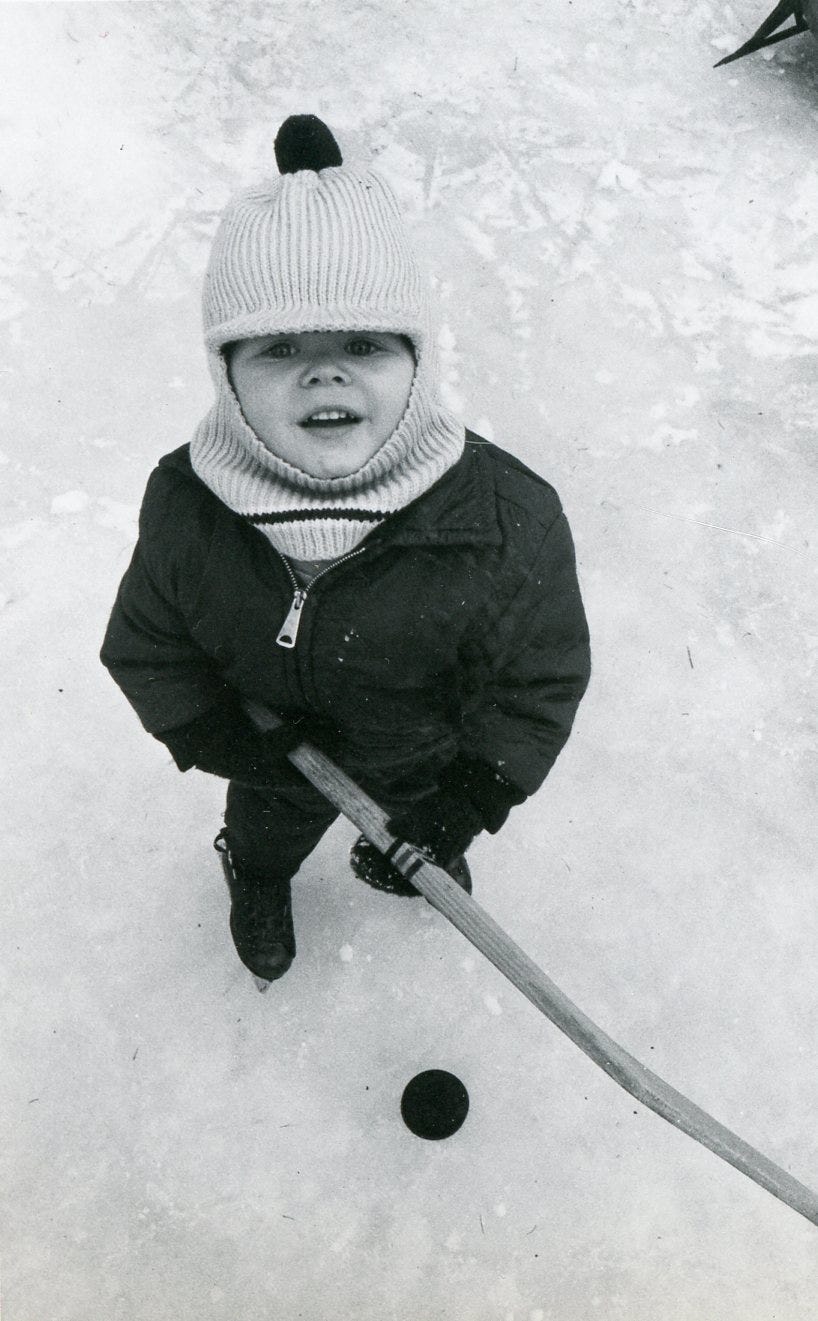

I played hockey in the East York House League straight through to the end of high school. I started when I was maybe 6 or 7. I started in "hockey school," beginning in the days before face masks. One of the exercises we were asked to do—why?—was skate across the ice, boards to boards, with our stick behind our heads. Halfway across I fell. Unable to use my hands to break my fall, as they were above my head, behind my stick, I braced my fall with my chin. Blood exploded. I was rushed to hospital—many stitches. A scar I retain to this day.

I have a clear memory of blood and another one of being covered the green cloth over my face, as the doctor leaned in with a needle. Sharp pain. Possibly not worse than that experienced by my mother, who was watching me cross the ice towards her when I fell and split my head open. Injury, blood, pain, and trauma aside, I returned to hockey school (the next year?), this time with a chin guard attached to my helmet, much to the amusement of the other kids and spectators. Soon, we all had face guards.

One Saturday, I went to hockey school, and a coach from one of the league teams approached my father. Would I be interested in playing for their team? Their team was called Whitby. My father thought the team was in Whitby, but the age appropriate league was named after regional municipalities. They played at the East York Memorial Arena, same ice surface as the hockey school. I had been promoted. In those days, I was also playing ball hockey one night a week at the local elementary school. My parents sat my brother and I down. We could play ice hockey or ball hockey, not both. It was easy. Ice hockey could continue, including the occasional 6:00 a.m. rise for an early, early game or practice. I loved it.

I still sometimes have hockey playing dreams. I imagine myself in a game, looping around the ice, swooping in patterns, the puck passing between players, offence, defense, collisions, scoring. In our league at the time, hitting started young. Later, it got moved back, but I don't remember a time without hitting. I played defense—because, well, Bobby Orr—and if you're going to stop players from moving in on your net, you have to use your body to stop them. You don't need to flatten them, but you need to get significantly in their way. I became reasonably good at that. Later, when everyone got bigger and faster, the hitting became more significant, and it became necessary to learn how to avoid getting crushed, "take a hit," in the vernacular.

At school, I was quiet, perceived by some, I'm sure, as "nerdy." But on hockey night, I could take a hit—and dish them out, too. One year, the first game of the year, one of the kids from school saw I was on his team, and he made a sarcastic comment. After the game, though, he said: "Bryson, you're actually pretty good!" Well, duh. My team in 1982-83 was the best ever. We won the championship, and I was the MVP, except I wasn't there for the championship because the family had gone to England that week. Still, my coach admired me, and he saw I gave my all and inspired the other kids. It would have been nice to have been there for the winning, final game, though!

In addition to the weekly house league game, I went frequently to Dieppe Park, Cosburn & Greenwood, night after night, where they had two rinks, one for pleasure skating, one for anything goes hockey. Helmets were not required. You would go, see who was there, form up teams, and play. Usually, there were multiple games happening on the same ice at the same time, plus other lone wolf skaters, who were firing puck this way and that. It kept one alert and cautious. One night I went in a deep freeze. It was almost empty. I returned home, lucky to avoid frost bite, though my ears ached for days.

In high school, I also played late Friday night with a group of guys, connected from here and there. The original organizers of this group were some dudes a bit older than me, some connected through church, some connected through who knows where. One guy wore #99, and we called him Gretzky. I wore my #17. We didn't wear helmets. Our ice time was midnight to 1:00 a.m., but if no-one came on after us, we kept playing until we collapsed. One house league game in high school, I brought the puck around the net and slammed straight into an opposing player. I bit my tongue on the hit, and it swelled and turned dark purple for days, which I made sure to show everyone at school.

I had photos of Wendel Clark clipped from newspapers across my bedroom wall. I remember seeing his mother, I believe, on CBC saying she'd advised him as a junior player, after he'd been beaten up: "You have to get in there faster, up and underneath!" That was Wendel, his first year. He would drop his gloves in an instant and pummel the other player so fast, it was over before it started. But he could score, too. He would glide down the wing, pull back his blade, and release a long wrist shot. Like his fighting, it was quick, unique. And he was paired with Russ Courtnall and Gary Leeman on a youngster line, branded the Hound Line. CBC played it up, creating graphics and a song. I looked for it online. ... Anyone?

In the early 80s, it was all boys playing hockey, but Justine Blainey won the court case in 1986 that started to change that. Her mother taught at my high school, and I remember seeing her on TV.

So, Wendel was my guy, but in my heart of hearts, the Leafs team that was my Leafs team, was Darryl Sittler's team, the team of the late-1970s, when I was 10 years old, give or take a year or two. I could probably still name more players off of that team than any other, and that's the team that popped my Leafs cherry. Toronto defeated the New York Islanders in overtime in game 7. Lanny McDonald scored on a wrist shot over a sprawling Billy Smith, and I have an image of it still. In the semi-finals, Toronto met the Montreal Canadiens and fell in four straight. Montreal went on to win the Stanley Cup, one of four-in-a-row. Disgusted, I tore up all of my Canadiens hockey cards.

I even remember Red Kelly and his dummy pyramids (1976), and why hasn't there been a bio pic of Harold Ballard? Toronto in the 1970s, what was going on? It's ripe for— not revival, no—reassessment, or maybe just satirical exploration. Hmm.

I tried out—once—for my high school hockey team, grade 13, last chance. I got up early, mid-week, and went to the first try-out. Quickly, I realized I was not that good. Also, I was not that big. These boys were thick, chunky, heavy, and prepared to be mean. I had to do an exercise to pounding backhands. I couldn't with any consistency. They didn't call me back, but a couple players from the high school team were on my house league team that year, dudes younger than me. One hotshot decided he would play the whole game. Every time there was a shift change, he just stayed on the ice. We all knew he was our best player, but WTF. Get off the ice! That year, I was one of the photographers for the year book. I took the team photo of the hockey team. That's as close as I got to the real thing. My house league teammates gave me props, though. #respect

When I went to university, my residence had a hockey team, and it was at the house league level, so that was okay. I also played some in the weekly Mennonite league, squaring off against farm boys, which was terrifying. Playing in the Mennonite hockey league might be the only place where I legitimately considered I might be murdered. Once, I very nearly was, ducking just in time to avoid a massive, homicidal collision.

My first year at university was 1987, year of the greatest hockey games ever played, the 3 games between Canada and the USSR in the Canada Cup. I know there are those who say 1972 was the pivotal series, but 1987, man. Gretzky, Lemieux, on the same line? Are you kidding me? As I noted in my piece on Ottawa (1991), I saw Gretzky up close over multiple days in the LA Kings training camp in Hull. Also in 1991, there was another Canada Cup, and they had an intra-squad game in Ottawa that I saw. This was the camp with the just drafted Eric Lindros.

Lindros was fresh off of being taken by the Nordiques with the first overall pick in the draft. He refused to sign with the team, and was adamant that he'd never do so. There was still some skepticism lingering over whether he'd actually follow through on that threat, but it's fair to say that he was already a controversial figure by the time the tournament rolled around.

That didn't stop Keenan from putting him on the team, and the hockey world got their first look at Lindros against NHL-caliber talent. He didn't disappoint, making an impact early on – literally. He crushed Swedish defenseman Ulf Samuelsson and Czechoslovakian winger Martin Rucinsky with clean hits, knocking both out of the tournament.

Lindros finished the tournament with three goals and five points in eight games, before heading back to junior to make good on his promise to never play for Quebec.

It was Canada against Canada, red against white, and they played fast and furious. I believe there was even a fight.

I last played hockey as a team sport in an old-timers league at Ted Reeve Arena, 2003. I had Bobby Orr's knees by then, and no interest in taking any more hits. I played on a team that year with my brother and one of his buddies. The other guys were locals, hanging on to glory days. One game I was awarded a penalty shot, first of my life. The best scorer on the team said to go in, fake a shot at the hash marks, then shoot quickly between his legs. I did as instructed and scored. It was the last locker room I'd be in, I guessed. It was full of, yes, locker room talk. I reminded me that once, in high school, one of my team mates asked if anyone knew how he could get rid of a stolen car. In my last locker room, someone bragged about his local rub and tug.

Given the ubiquity of hockey in Canada, it's surprising there isn't more literature centred on it. In junior high, I read a couple of Scott Young's hockey adventure books, not knowing he was Neil Young's father. Probably at that time, not knowing who Neil Young was, either. Hockey is laced through Mordecai Richler's various portraits of Montreal, notations about the beauty of Beliveau, the tenacity of Rocket Richard, characters essential to the culture of the city. I remember reading Lynn Coady describing hockey: skate, skate, shoot, shoot. Something like that. She later wrote a novel about a bruiser, The Antagonist (2011). I wrote a review of Coady’s novel for The Winnipeg Review, which I see is now no longer online, so I will paste it below. I also wrote a short review of Mark Anthony Jarman's Salvage King Ya! (1997), which included a line later used as a cover blurb: "If it's the best hockey book ever written, does that make it the Great Canadian Novel?" (How is 1997 twenty-five years ago?)

Al Purdy wrote a poem calling hockey a combination of ballet and murder.

Conn Smythe was wrong when he said if you can't beat them in the alley, you can't beat them on the ice. That might be the original Maple Leafs curse. The other might be how they treated Dave Keon. (Dave Bidini’s Keon and Me (2014) is apparently great.) I have no recollection of Keon, but whenever anyone speaks of him, I'm reminded of how I felt about Clark in those early days. He inspired the belief that the odds could be overcome, if enough pressure was applied. Get up underneath, quick!

Leafs Nation? Sure, okay. Leafs as Kafkaesque metaphor. Surely.

*

ADDENDUM: Must add the update that the Leafs lost the series of the Tampa Bay Lightening, so their quest to win a playoff series continues. A couple other hockey stories. In late high school I thought I might try becoming a volunteer referee. One of my friends’ father was one. He encouraged me and loaned me the training material. It suddenly seemed much harder than want I wanted to take on. Then a friend asked if I would volunteer to referee a pick up game, be one of two on the ice. I said I would. I really hated the experience. I could call the off-sides and icings, but I didn’t want to call penalties. I guess I could have been a linesman.

I can’t believe I missed the story about the game I played goal. I was the captain of the team. Possibly it was that year I won the MVP. Our goalie didn’t show up. The coach asked for volunteers. I volunteered. I suited up and skated on the ice and into the net. My mother in the stand spent half the game trying to locate me. We lost something like 10-1. I could not stop the puck. I played net in ball hockey, and I could stop the ball by putting my feet together. On the ice, your skates don’t go together. You need to stop the puck with your stick and close that hole. At least 3 goals went in that way. After the game, my mother was mortified and thought she would need to console me, but I bound up the stairs from the locker rooms, laughing my head off. Playing goal: another thing I would never do again.

My brother and I once went to Maple Leaf Gardens and someone yelled from the stands (at Al Secord): “Shoot that thing!” It became one of our sayings, whenever we watched a hockey game. “Shoot that thing!”

I married Habs fan, people.

I made some comments about the source of the Leafs curse. Online I saw someone make a similar comment, referring to the sexual abuse of minors that happened in Maple Leaf Gardens in the 1970s and 80s. Martin Kruze was one of those victims and did much to bring the facts to light. In 1997, he jumped to his death from the Bloor Viaduct, prompting the City to do what others had been asking it to do: put up a suicide barrier on that bridge. Every time I cross that bridge, as I did this past week, I look at those barriers and remember. A horrific legacy.

*

[Originally published in The Winnipeg Review, September 26, 2011]

The Antagonist

by Lynn Coady

Anansi, 2011

Gordon Rankin is a big guy. A really big guy. He's so big he needs to be careful not to get angry around women because then they cower at the sight of him. Dudes, on the other hand, look at him as a kind of challenge.

Sure, he's big. So what?

I can take him.

But no one can. No one quite knows what to do with him, and he's more than a little lost himself. Adopted into a "down East" family (the location is never specified, but it's clearly in the Maritimes), Rank, as he's known, picks up a habit for casual violence in his teens and one altercation results in permanent brain damage to his opponent.

But that's not the real story of Lynn Coady's strong new comic novel, The Antagonist (Anansi, 2011).

The real story takes place twenty plus years later when Rank discovers that a university friend whom he hasn't seen in two decades has used him as a model for a novel. In the novel, the big oaf, a hockey enforcer like Rank, is described as having an "innate criminality." Then he kills someone. Like Rank, when he was a teenager, his mother died. The Freudian connotations flow from cause into effect.

Except that the real Rank disputes that A leads to B.

This is the story of Coady's novel. Rank writes a series of emails to his once upon a time friend, arguing that the novel within the novel got it all wrong.

And, not to give it way, he proves his point.

The emails are dated in between May and August 2009. They are, for the most part, one-sided. The readers do not get to see the replies sent by Adam, the ex-friend and novelist, such as they are. What we get is the story from Rank's point of view, and the story is Rank was surprised to find himself portrayed in a novel. Shock! Horror! Dear Author, Rank writes, I have a story to share. It's the story you missed. Listen up.

But, of course, there's more to it than that, and thank goodness, because Rank can be a dunderhead. He's upset how he's been portrayed, but there's a lot of self-reflection he hasn't done, and his lack of self-awareness can be grating. That's a minor criticism, though, because Rank -- the hockey goon -- turns out to be a great writer. All he needed was a laptop and a shot of motivation.

So who is the antagonist?

My Oxford Concise Dictionary gives the primary definition of "antagonist" as "an opponent or adversary." The secondary definition is "a substance or organ that partially or completely opposes the action of another."

The simple answer is that Adam, the author, is the one who opposes Rank. Adam is the one to whom all of the emails are aimed (though they are addressed to "you," and sometimes the reader can start to feel the weight of the blame). Another answer, however, can be found if we stand back and look at what the novel and the novel within the novel have in common. That is, Rank's life.

Who is Rank's antagonist?

Not surprisingly, perhaps, it's his father. His English-speaking working-class father, who married his French-speaking working class mother, and both adored her and treated her like shit and provided Rank with what Adam later calls a "virgin-virgin complex." In other words, a view of women that is idealized and, by definition, unrealistic.

To explain this more would be to give away parts of the novel that the reader should discover for herself. What can be said, however, is that Adam's novel missed the father story, and Rank fills it in with exuberant detail.

"They got Frenchies all the way up here now, do they?" is Dad's pick-up line.

Somehow, it works.

Rank doesn't understand it either, and, approaching forty, he's still trying to make sense of his life. It's worked out, on the whole, despite his size, his poor decisions, his dysfunctional family, jail time, travelling about, massive drinking and drug taking, and early exposure to T.S. Eliot.

And, yes, it is a comic novel. Which means I can't give away the punch line.

That would be cruel.

I don't want to oppose one action or another.