The Book of Grief and Hamburgers

by Stuart Ross

2022

What a tender book this is, written (as the back cover states) "during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, shortly after the sudden death of his brother—leaving him the last living member of his family—and anticipating the death of his closest friend after a catastrophic diagnosis."

The back cover also calls this slim volume a "literary shiva." Shiva, in the Jewish tradition, via Wikipedia:

During the period of shiva, mourners remain at home. Friends and family visit those in mourning in order to give their condolences and provide comfort. The process, dating back to biblical times, formalizes the natural way an individual confronts and overcomes grief. Shiva allows for the individual to express their sorrow, discuss the loss of a loved one, and slowly re-enter society.

Note the lack of hamburgers in that description. Hamburgers is a Ross innovation. As a fellow writer once pointed out to Ross, "whenever one of his poems was getting heavy, he'd stick in a hamburger for comic relief" (back cover). There's a lot of hamburgers in this literary shiva—a lot of heaviness, too—but comic relief and a tough vision of the world is what we expect from Ross. Here he provides his most revealing, and heartbreaking, work yet.

Some comments on grief. I have two books on grief I always recommend, and then there is one that others invariably mention: Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking (2005). The thing about Didion's book is that it's not a book about grief; it's a book about "complicated grief." She slides deeply into magical thinking because she is grieving two major losses at the same time, and her ability to cope and process the events is greatly disrupted: her husband dies suddenly, collapsing at the dinner table, and their adult daughter has a severe medical condition, which ultimately leads to her death. In some ways, Didion's book is about un-grief, the inability to grieve. Because grief is a verb; it is an active processing of emotions; it is a journey of change.

The stages of grief. You hear that a lot. I heard it just this morning on CBC radio, someone dropped it into her commentary. The stages were popularized in the 1970s by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Recent research on grief confirms those stages happen, but not always in that order, and frequently not in a liner manner. Susan A. Berger's The Five Ways We Grieve (2009) provides an updated overview of grief as process, or rather grief as narrative. She suggests there are five patterns of grief-as-transformation. For example, spouses who lose their partners may quickly remarry, attempting to recreate the status quo. Others may sell everything and move to a far corner of the earth, attempting to start from a clean slate. Families may set up a foundation dedicated to researching the disease that took their child, attempting to save other children, as they could not save their own.

The other book I recommend is Healing Through the Dark Emotions: The Wisdom of Grief, Fear, and Despair by Miriam Greenspan (2003). This book was recommended to me by someone who'd lost her four-year-old son to cancer. It also follows the grief-as-transformation approach. Grief is not a hazy, crazy cloud you go through, only to be returned to yourself. Grief picks you up, spins you around, returns you to a place you have never been before. There is no going back, there is no returning to your former self. Except grief does not pick you up; it pushes you down; because grief is a journey through the underworld—where you face complications before emerging, transformed.

The grief described by Ross is definitely complicated. He has lost many people, family, friends, mentors, who have been the gateposts and structure holders of big parts of his life. There are not enough hamburgers in the world to fight off the waves of deep sadness, even contemplations of suicide. A numbness accumulates—though stronger is the vibration of life. Because Ross provides a portrait of the artist through his clear statements of love and admiration for the writers and friends who have inspired and encouraged him. How can one keep eating hamburgers after these giants are gone? (I use this metaphor even though Ross says in the book he's a vegetarian because, well, it's his metaphor.) The eating of metaphorical hamburgers? The eating of veggie burgers?

To be or not to be, that is the question. Or is it? Perhaps it's more, how can one be now that everything is different? This is where grief-as-transition is critical. Because one cannot be. The past is gone, so one is gone, too, but one can be renewed. One can re-emerge from the underworld, the A&W of Griefland, carrying plates of hamburgers. Garnished however you like.

This is a lovely book, Stuart, thumping with love. Thank you for allowing us to sit shiva with you.

*

Below are two reviews of other books by Ross, one published in The Danforth Review (2004), one on my blog (2009). Where does the time go? The blog one is odd, yes, intentionally so. I tried to write a review in the style of a Stuart Ross short story. So it goes.

*

TDR Interview with Stuart Ross by Dani Couture (2004)

*

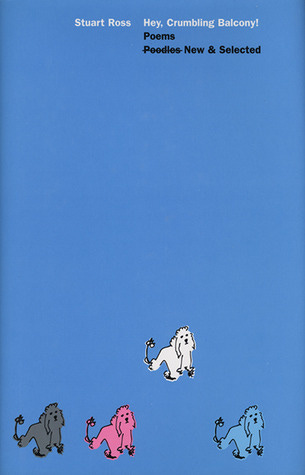

Hey, Crumbling Balcony!

by Stuart Ross

ECW, 2003

Hey, Crumbling Balcony! ... a great title for a book, a terrific title for a book by Stuart Ross. (See also Ross's website: https://bloggamooga.blogspot.com/.)

Here's a bit of the title poem (which is actually called "The True, Sad Tale of Benjamin Peret as it Relates to Me"):

Hey, balcony crumbling outside my window,

whose concrete organs plummet to the parking lot below,

know this: Benjamin Peret died in 1959

and in that year I was born.

He was photographed

in a toreador's get-up,

and thus was I born, hat and all

waving a cape at Dr. Bernie Ludwig,

I've the pictures to prove it.

If you haven't read anything by Stuart Ross, Hey, Crumbling Balcony! is your one-stop shopping experience to catch up on the work Ross has been contributing to Canlit in chapbook after chapbook, and other work, since 1978. Subtitled "Poems New & Selected," Hey, Crumbling Balcony! is one of the milestone tomes of 2003. It is also a profoundly peculiar book ... or rather, a book full of the peculiar yet profound.

In thinking about what to write in this review, those two words kept coming to the fore: peculiar, profound. The sample quoted above provides enough of an example. Normally, one would accuse writing that addresses an inanimate object (balcony) as if it were a live, thinking, feeling thing (hey) of one of the basest of flaws: "The balcony is not listening, Stuart." But Ross's writing demands its own rules. In Ross's world, the balcony is listening and thinking and more than likely feeling. Salvador Dali is not Rembrandt, and Ross is not Dickens; he is closer to Kafka, Lewis Caroll, and Dr. Suess.

Like the work of those writers, what is perhaps most striking about Ross's work is the originality of its point of view. It is strange, yes. But it is not scattergun weird. It is patterned; it is consistent; it is art. Ross gives us a re-imagined world, and the shape of that world becomes clearer as one reads poem after poem. Ross's poetry is marked by a singular peculiar vision, echoing with profundity, sustained over time.

His poems often mix concrete detail (often images of marginalia, decay, weakness ... a crumbling balcony) with flights of surrealism. But there is more than surrealism in Ross's work. At least, there is more than weirdness. I am tempted to say, "There is truth," but what is that? Perhaps this quotation from George Saunders provides a clue. Saunders is the American short story writer, whose own writing is a tad odd. In this quotation, he is speaking of where his writing comes from:

What took me a really long time was realizing that just using my internal voice was all right, and it was the one I actually had to use. That internal voice was not anti-artistic, exactly, but it wasn't one I'd seen or heard before. I can remember thinking, You mean I should write that way, just like I think? It was really liberating for me to say, "I'm going to be a goofball for the rest of my life. I'm going to be a ninety-year-old guy with a fart cushion." It took a great weight off my shoulders.

That's truth. Feeling free to be yourself. Putting on the page the voice you hear in your head, and not trying to filter your voice to please anyone else: parents, teachers, publishers, editors, readers.

Ross's voice resonates with integrity. The voice is his poems echoes Kafka in that his narrators are often victims of the world's absurdities. His poems echo the work of Dr. Suess in their whimsy. At base, however, the poems belong to Ross alone. They speak human truths, human realities. The repeated message is: It's a strange world out there, a world with few solids, a world within which the only thing stable is instability.

There are references to the real world—Benjamin Peret, Ross's childhood friends, Randy Newman ... attempts at connection that never seem to connect ... but there is also deep feeling. Isn't this a deeper kind of realism? It is the way the world is. Fragmentary. Always on the verge of collapse.

Some may find these poems freakish; they are lovely.

*

Buying Cigarettes for the Dog

by Stuart Ross

2009

It's easy to misunderstand Stuart Ross.

When I say Stuart Ross, I don't mean Stuart Ross, the man, the individual, the writer, the poet, the blogger, the event organizer, the publisher, the person-who-does-things.

I don't know this Stuart Ross, whom I nonetheless believe exists.

Yes, I've seen him, or someone resembling him, or imitating him.

I've even reviewed a book purported to be by him. It didn't make a lot of sense, but I enjoyed reading it.

When I say it is easy to misunderstand Stuart Ross, this is the Stuart Ross to whom I am referring.

The Work. The Words On The Page.

As in, "So what do you think of the New Stuart Ross?"

Like, "What do you think of Hemingway?"

When one is asked if one prefers the early or the late Hemingway, one doesn't imagine he or she is being asked if one prefers the one with the beard over the one without.

Like, "What do you think of Kafka?"

One would say: "I dunno. I don't get what he's up to." For example.

One is perplexed by what Stuart Ross is up to, for example, in Buying Cigarettes for the Dog (Freehand Books, 2009), the author's new short story collection.

One cannot agree, however, with the last sentence in the book: "My stories are of no consequence."

These are stories of consequence. They're just easy to misunderstand.

*

Lorrie Moore recently reviewed Hiding Man: A Biography of Donald Barthelme (St. Martin's, 2009) for the New York Review of Books.

In that review, she wrote:

The placement of unexpected things side by side is not only the spirit of surrealism but also the beating heart of both comedy and nightmare, and Barthelme's work, despite its seemingly offhand oddness and its flouting of conventional storytelling, was capable of suddenly cohering in the marvelous way of Kafka.

She also noted that in Barthelme's writing ...

Conventional narrative ideas of motivation and characterization are dispensed with. Language is seen as having its own random and self-generating vital life, a subject he takes on explicitly in the story "Sentence," which is one long never-ending sentence, full of self-interruptions and searching detours and not quite dead ends (like human DNA itself, with its inert, junk viruses), concluding with the words "a structure to be treasured for its weakness as opposed to the strength of stones."

Moore doesn't appear to be overly thrilled with the biography, but she does link some of Barthelme's genius to his geographic past:

He was a rainbow coalition ventriloquist and his denser stories perhaps gasp for air. That his first three decades were spent in Houston, a sprawling city without zoning ordinances and resplendent with surreal juxtapositions (billboards next to churches next to barbeque shacks), must have been a deep and abiding influence - though his early reading of Mallarme is usually given the credit.

*

When my five-year-old step-daughter asked me what I was reading, and I said it was called Buying Cigarettes for the Dog, she laughed loud and long.

"Daddy reads funny books," my wife said.

[The previous book I read was Thought You Were Dead by Terry Griggs (Biblioasis, 2009).]

*

Stuart Ross is the editor of Surreal Estate: 13 Canadian Poets Under the Influence (Mercury Press, 2006). He may well be Canada's leading literary surrealist. He deserves more close reading than he currently gets. Donald Barthelme was a superstar. Stuart Ross is a small press racketeer (Anvil Press, 2005).

Joanna M. Weston found in Ross's I Cut My Finger - Poems (Anvil, 2007) an author full of hope:

Poetry for an evening by the fireside with a bottle of wine. Poetry to be savoured, relished, enjoyed. Ross writes of hamburgers and history, of oceans and orphans, of sonnets and self-portraits with what appears at first glance to be humour, but underlying the piled on images is a realistic, often optimistic, view of the world. The prince will always kiss Sleeping Beauty into wakefulness, will always bring the glass slipper to Cinderella.

Ross links images in a dance of kaleidoscopic colour and shape while maintaining rhythm and the cohesion of underlying emotion with serious impact. He gives a sense of adventure and wonder to each page; the reader can never be sure what might happen next.

*

Like I said, it's easy to misunderstand Stuart Ross.

*

The reader can never be sure what might happen next in the stories in Buying Cigarettes for the Dog.

One reason for that is the placement of unexpected things side by side. Another reason might be because Ross is a resident of a sprawling city ... resplendent with surreal juxtapositions [but, yes, Toronto has zoning by-laws].

There are other reasons, too, for Ross's literary peculiarities. One might find some possibilities by looking at what Wikipedia notes about Kafka's writings: "Themes of alienation and persecution are repeatedly emphasized."

The website contextualizes critical responses to the Czech - German - Jewish - Modernist writer:

Critics have interpreted Kafka's works in the context of a variety of literary schools, such as modernism, magical realism, and so on.[22] The apparent hopelessness and absurdity that seem to permeate his works are considered emblematic of existentialism. Others have tried to locate a Marxist influence in his satirization of bureaucracy in pieces such as In the Penal Colony, The Trial, and The Castle,[22] whereas others point to anarchism as an inspiration for Kafka's anti-bureaucratic viewpoint. Still others have interpreted his works through the lens of Judaism (Borges made a few perceptive remarks in this regard), through Freudianism[22] (because of his familial struggles), or as allegories of a metaphysical quest for God (Thomas Mann was a proponent of this theory[citation needed]).

Stuart Ross is not just strange and awkward. He is often profound.

And funny.

Here's Wikipedia on Kafka again:

Biographers have said that it was common for Kafka to read chapters of the books he was working on to his closest friends, and that those readings usually concentrated on the humorous side of his prose. Milan Kundera refers to the essentially surrealist humour of Kafka as a main predecessor of later artists such as Federico Fellini, Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes and Salman Rushdie. For García Márquez, it was as he said the reading of Kafka's The Metamorphosis that showed him "that it was possible to write in a different way."

Ross is widely read and admired within the tight circles of Canada's small press readership.

It's everyone else who needs to wake up and get some learnin'. Something along the lines of it's possible to read in a different way.

That is a matter of not insignificant consequence.

*

I haven't said much about the specifics of the stories in Ross's new book. I find that I don't want to. I want you to discover them for yourself.

You will misunderstand them. I can almost guarantee it.

I did.

Excellent review. I sent it to Stuart in case he hasn't seen it.