“Religion is deep entertainment,” Leonard Cohen said once. I remember reading that in a profile of the singer-songwriter-poet, perhaps after the publication of Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs (1993) or around July 1993 when, as part of a tour in support of his album The Future (1992), he appeared in Saskatoon, where I was living at the time. Friends of mine ran into Leonard and Rebecca De Mornay out walking beside the South Saskatchewan River.

I thought that was a good line: deep entertainment. I might have said the same thing about literature, though. It’s not about Marvel movie heroes and sugar sweet pop songs. Real religion is more punk, getting past surface facades and down to the rich earth. “Leave to Caesar what is Caesar’s,” the Christ said. We are concerned about other things.

We are concerned about depth; meaning; purpose. “What is real and what is not,” Dylan sang. And to this day, if I’m honest, this is the well I go back to. I don’t call it religion anymore, nor do I barely call it literature. But I have an aching for something fundamental, something foundational. I recently read Sarah Polley’s essay collection, Run Towards the Danger (2022), and I admire her moral clarity and how she connected it to established facts, the stories of others, and speaks clearly about how she interprets the ambiguities. She is not religious, but she seems driven like an Old Testament prophet, offering necessary corrections.

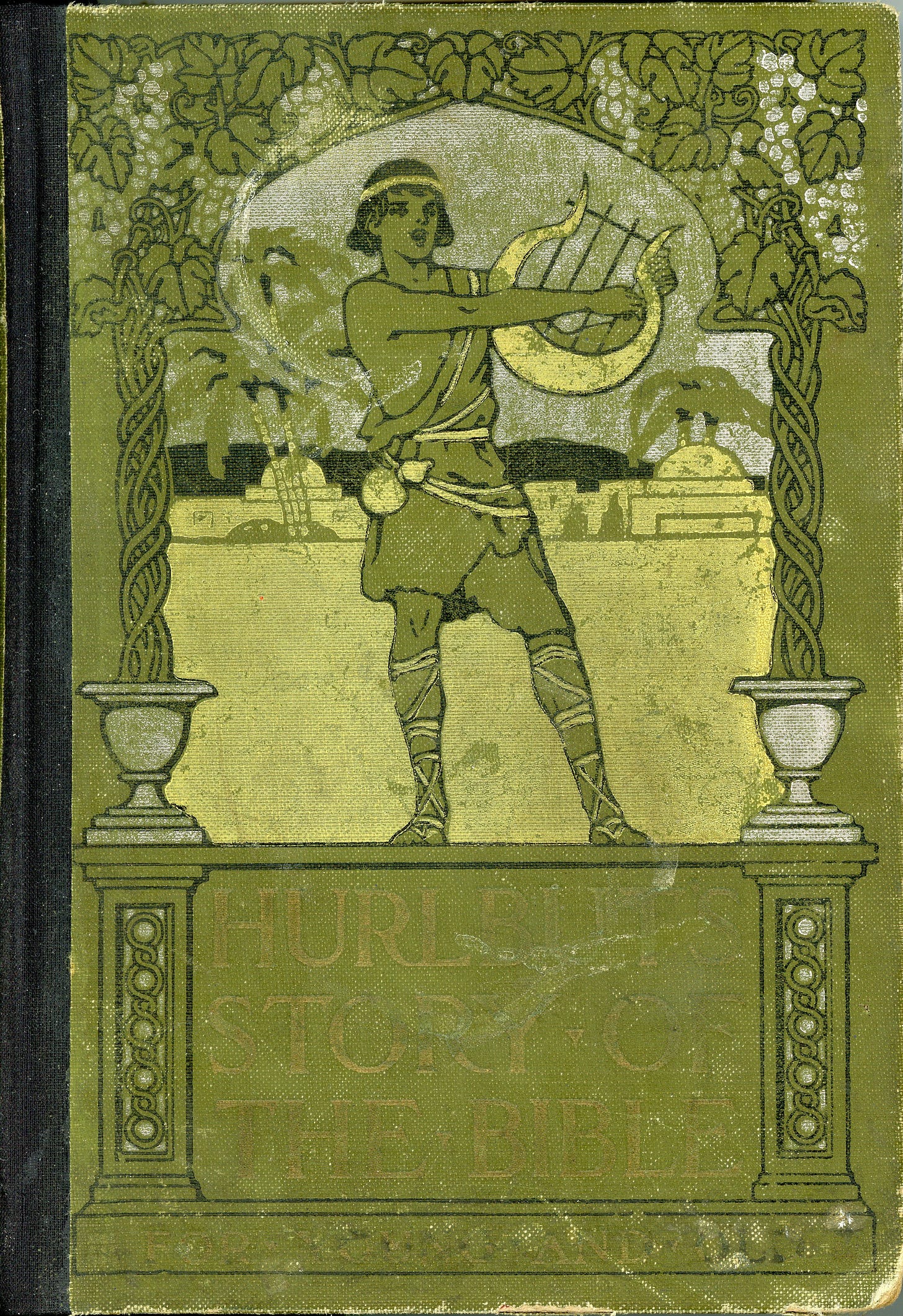

How I came to be in Saskatoon in 1992 goes back to 1977. The original title of this piece was “Green Bible,” which is what our family called Hurlbut’s Story of the Bible (1904). I needed to reference a book, and this is going to have to be it. (Either that or Martyr’s Mirror.) It’s not specifically the cause of my move to Saskatoon, but more on that later. What happened in the mid-1970s is that my mother ran a daycare in the basement of Woodbine United Church (Woodbine and Mortimer), which is where we attended on Sundays. But the church management booted her out because they wanted the space used by someone who would pay more rent. Two of the mothers who used this daycare were members of the nearby Danforth-Morningside Mennonite Church (Danforth and Woodbine).

“You can use our church basement,” they said, and my mother did. Leaving Woodbine United behind on Sundays, too.

My father stayed at Woodbine United for a while, until he attended a Christmas concert at the Mennonite church and got to talking to the part-time pastor, who told him that Mennonites were about “faith in works,” something my father strongly identified with. Getting things done, not just talking about it, not resting on belief in words. He told everyone who would listen he had found his spiritual home, the world of Anabaptists. He had never believed in infant baptism, didn’t have his two sons baptized. He didn’t believe in war and felt he’d always been in the pacifist groove.

So we became Mennonites. At least, kind of, sort of. I was under 10 at the time, and to me a church was a church was a church. Or, as we muddled our phonemes, “turch,” is what we called it. But this was a big shift, and in the 15 years between 1977 and 1992 it affected almost every element of our lives. Obviously, the influence didn’t stop in the early-1990s, but this is the period I’m concentrating on here.

Woodbine United Church doesn’t exist anymore. It was knocked down decades ago and replaced with an apartment building. What I remember about it most, is the basement, where I went to Cub Scouts. I also have a memory of being in the basement, preparing to go upstairs into the main sanctuary for some ceremonial event. I remember being in the main sanctuary and singing “Onward Christian Soldiers,” a rousing tune. I remember wondering if the Mennonites would sing it, because it contained the word soldiers and spoke of “marching as to war.”

My father had been brought up in the United Church, and we went to the United Church in Grafton when we visited my grandmother, who played the church organ with her shoes off, all the better to feel the pedals. She also led the choir, and I remember the red hymnals with a fine gold cross pattern on the cover we would use to sing along. The United Church also had a special book for “readings,” which the Mennonites didn’t have. I started to become aware of the differences and what we had left behind.

My grandmother was deeply religious, as was my father, who wasn’t the first of his siblings to “convert.” Two of my uncles converted to Catholicism, and one later attended a parish in Ottawa that served the Latin Mass. My mother was not raised in a religious household, but her father was raised a Northern Ireland Presbyterian, which would also have been the original denomination of the Brysons, who arrived in what is now Ontario in the mid-1800s, later converting to Methodism (later the United Church), probably because of the temperance movement against alcohol. Which is to say, there is a lot of orange in my background, but some green branches, too. There was a broad openness to questing and finding your own solution. Sort of, kind of. Parts of the extended family weren’t pleased with my first uncle’s Catholic conversion, I’ve been told and reminded even in recent years, though that happened in the 1950s.

When I was born, my father’s Aunt Laura told my parents, “There has never been a Michael Bryson. Michael is a Catholic name.” LOL.

From Wikipedia (March 27, 2022):

Saint Michael the Archangel is referenced in the Old Testament and has been part of Christian teachings since the earliest times. In Catholic writings and traditions, he acts as the defender of the Church and chief opponent of Satan and assists people at the hour of death.

This seems like a good spot to add that my family came from a small town in Ontario that had an Orange Lodge, though there is no evidence that my father were ever members. Still, since 1930 there has been a summer family picnic, and to this day folks remember the traditional date of the picnic as the “second Saturday in July.” I told this story to a Catholic-raised friend of mine.

“The second Saturday in July is another way of saying, the Saturday closest to July 12th. People remember the ‘traditional Saturday,’ but they don’t remember why.”

My friend said, “You should write that. That’s a good line. ‘They met every summer on the second Saturday in July, but couldn’t remember why.’”

My maternal grandfather had a joke. He moved to England in the 1930s, where he remained for the rest of his life. One day he called one of his brothers in Belfast to tell him he’d converted. “Yes, I’ve gone to natural gas.” LOL. He grew up on Castlewellan, County Down, the son of a shopkeeper. He studied at the London School of Art and Design, learning many crafts, including stained glass. St. Paul’s, Church of Ireland, Castlewellan, houses three windows designed by him at that time, including one (St. Matthew) dedicated to his mother (my great-grandmother), Martha. Castlewellan is a largely Catholic area. When I visited in 1989, buying a Mars bar at my great-grandfather’s store (now the Post Office), British soldiers patrolled the street outside.

My father read to me and my brother from “The Green Bible” at bedtime. I don’t think we made it up as far as the New Testament, because the stories I remember see Israel stray and God send a prophet to return them to the proper path. I still remember I was shocked that Moses wasn’t allowed to enter the Promised Land after wandering 40 years in the desert, because he ... what did he do again? Okay, I had to Google this, and … interesting.

In the late-1970s I attended R.H. McGregor Public School in East York. I can tell you with certainty that there were no other Mennonite kids in that school. What there were, was kids from all around the world. My father was fond of telling a story about a visit he took to the school around that time. He asked the principal if the school offered French immersion. The principal said they didn’t: “We have a hard enough time teaching the kids English.” The students represented 75 different nationalities.

So, in public school this shift in churches wasn’t consequential, but as I got older the dissonance increased. Around my buddies, it didn’t matter. We went to school, we hung out, we played hockey, baseball, football. I was part of a Scout group. We played cards, went camping. Girls entered stage left. I got a job as a weekend janitor at the senior citizens’ complex the Mennonite church had built in partnership with another local Mennonite congregation. Faith in works. Getting things done.

By this time, my parents had branched out and encountered the broader Mennonite community in southern Ontario, discovering that there were in fact two different communities: one derived from Russians who left the motherland after the 1918 Revolution, and one derived from Swiss German heritage who had arrived in Ontario from Pennsylvania. Other Mennonite communities began to emerge in East Toronto in the 1980s, with pastors dedicated to serving Chinese and Latino communities. The Russian Mennonite branch was especially supportive of immigrant communities, referencing their own immigrant experience.

What there wasn’t, was an Irish branch of Mennonites, though in 1992 my father would reach out to a church worker in Belfast who was working on a Mennonite-related conflict resolution project in that city. My father and I visited Belfast that summer, and the church worker, Joe is the name I remember, spent an afternoon driving us all over town, including the places that tourists are not supposed to go. I was staying with friends of friends in Belfast, while my father stayed with relatives. When I told the friends of friends, who grew up in Belfast, where I had been that day, they said they have never been to those places, which included the Falls Road and the IRA cemetery, where we found a Jim Bryson, a murdered IRA volunteer, buried feet away from Bobby Sands and the other hunger strikers. Joe wanted to show us the cost of the conflict, the price of peace.

(There is no evidence that this IRA Bryson is a relative. As noted above, my Bryson line is historically not Catholic.)

In 1987, I decided to go to the University of Waterloo to study English. Ultimately, I went to Waterloo because of the co-op program. I started in something called “applied studies,” which had an administrative training component. After the first year, I dropped out of that, but I remained in co-op. What Waterloo also had, was a Mennonite residence, Conrad Grebel College, which is where I bunked for four terms, starting in September 1987. This was my real Mennonite baptism, as I was suddenly surrounded by Mennonites, who were a whole lot more alike than the classmates from 75 different nationalities I was used to. I felt like a fish out of water. Did my best to pass.

Which I’m sure sounds strange to many, but it’s an accurate description. I’m just surprised that I was surprised. I mean, I knew enough about the broader Mennonite world to know that it wasn’t East York. My parents had gone to church conferences and encountered one statement over and over: “Bryson? That’s not a Mennonite name.”

No, it’s not.

If you don’t have the right key, you can’t open the lock. If you don’t have the right name, the right network of cousins, you’ll never really fit in. But I tried, and I tried, and I tried—while also staying grounded in East York, and England, and Ireland, and what remained of Methodism. Because Mennonites were changing, no? They had moved to the cities and were becoming modern, right? Yes and no. Poet Di Brandt came to read that the college the first year I was there. The students loved her. She wrote about this modernizing process. Patrick Friesen was another. One time I saw Rudy Wiebe give a talk, and he said his parents never learned English; they spoke “low German,” which included no word for “fiction”; the related concepts were “truth” and “lies.” How do you write yourself out of that? Write history-based fiction perhaps. Write non-fiction.

What Wiebe said was he did some education in Germany and concluded Goethe was writing about his place, and Wiebe asked himself what was his place? It was Saskatchewan. And who was the historic hero ghost of that place? Cree Chief Big Bear. I don’t think this is a conclusion any prairie-based Mennonite writer would draw today, but it won Wiebe the Governor General’s Award for The Temptations of Big Bear (1973). Perhaps of more interest, though, is Stolen Life: The Journey of a Cree Woman (1998) by Wiebe and Yvonne Johnson, great-great-granddaughter of Chief Big Bear. Unintended consequences reverberate.

Miriam Toews is on the Mennonite case now. I saw her speak after the release of Women Talking (2018), and she said she felt a kind of compulsion to address Mennonite malfeasance. Those weren’t her exact words, but you know: Will you ever stop writing about Mennonites? I wish I could, but “I feel like a Mennonite Sherlock Holmes. What are Mennonites up to now? I better go investigate.” Interestingly, Sarah Polley has written the screenplay and directed the movie version of Women Talking, coming soon (2022). (And Miriam’s mother calls my mother regularly to check in on her. They are church-connected. Faith in works. Getting things done.)

I am not compelled to address Mennonite malfeasance. In fact, at this point I couldn’t care less. I can name four Mennonite male pastors who have been outed by #metoo related accusations, for example, and those stories are horrible and sad, but these are not my people. Fix your shit, Mennos. Come on, you can do it. One time I attended First Mennonite Church in Kitchener and a pastor held up some iron bondage contraption at the pulpit and said this implement had been used by Catholics on the early Anabaptists, who were tortured for their faith. “That’s where we come from,” he said. I was not with him on that point. That’s not where I come from. And if Mennonites believe in the Ministry of Reconciliation, then that’s not where they should be either. If Mennonites have a Mission of Peace, then they should be making reconciliatory gestures towards Rome, surely.

I should hasten to add that I have met moral giants in my days among Mennonites. Menno Wiebe (1932-2021), the director of Native Concerns for Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), 1974-1997, comes to mind. In the summer of 1993, Menno led a group of us on a visit to Little Buffalo, Alberta, where we spent a week with the Lubicon Cree. More on this another time, but I took the photo below of Menno with Lubicon Cree Chief Bernard Ominiak. For more on the Lubicon Cree, see John Goddard’s 1991 book, Last Stand of the Lubicon Cree, or look up their website. More on the 2018 land claim settlement.

Menno had a prairie farm background, and he worked tirelessly and earnestly to build relationships between Mennonites and Indigenous communities. I asked him one time if he didn’t find it hard to get people to listen to each other, learn from each other, change their ways of thinking. We would call this work “Truth and Reconciliation” now, but in the early 1990s it was cross-cultural awareness or some such term.

“Of course, it’s tiring,” he said, “but if you are going to be a bridge between cultures you have to expect to be walked over from both sides.”

That’s the kind of bright shiny optimism—and tough-minded perseverance—that brought my father into the Anabaptist fold in the 1970s. For me, the light has long faded. And yet, I remain Mennonite-influenced and probably always will be.

Yes, it’s all a bit mixed up; it still comes down to words and deeds. Deep entertainment.

In the summer of 1988, I worked as a canoe instructor at Fraser Lake Camp. This was a Mennonite-run camp near Bancroft that had been bringing inner-city children and youth from Toronto for a summer experience since the 1960s. I had gone there as a child of about 12. This is how earnest I was; I brought my Bible, which I then never opened or removed from my bag, because I was in a tent full of teenage hoodlums. That term may be derogatory. Let’s call them a bunch of idiots. So much for my idealism. In 1988, I was more realistic. I once caught a 12-year-old smoking a cigarette and reported him to the office. I felt bad about that. Still do.

When my undergraduate degree came to an end in 1992, as the country slipped into a deep economic recession, I poked about for something to do, and my mother suggested I apply to MCC for a possible volunteer service position. Sort of like a Mennonite Peace Corps. I did apply, and in the summer of 1992 MCC called me and asked if I would be interested in going to Saskatoon to work at a non-profit conflict resolution agency, Saskatoon Community Mediation Services (SCMS). I said, yes. More on that another time, except to say the decision to go to Saskatoon reached back into the past, back to the 1970s and the fact that my mother’s daycare got kicked out of the basement of a church that was later knocked down to become an apartment block. Unintended consequences abound.

A note about “fitting in.” When MCC interviewed me by phone for this position, the woman from Winnipeg asked me, “Why are you marginalizing yourself?”

I had answered some questions on the application form in a way that indicated I wasn’t exactly a “mainstream Mennonite.”

“I’m not marginalizing myself,” I said. “I am who I am. Where the margin may be depends entirely on where you are standing and what you are perceiving.”

When I left Saskatoon in 1994, I took a part-time one-year contract in Waterloo as an editorial assistant at the Mennonite Reporter, which at the time was a bi-weekly national publication for Mennonites in Canada. I was happy to have only a part-time job because I intended to spend the other half of my time “writing,” which I sort of, kind of, did. I started to get short stories published in lit mags, finally. In 1995, I returned to school to do an English MA at the University of Toronto.

One of the pieces I wrote for the Mennonite Reporter had the headline: “Let Us Compare Mythologies.” That was the title of Leonard Cohen’s first book of poetry (1956). The piece was about a small Greek Orthodox Church located a few blocks away from the house where I grew up in East York. The priest of that church wandered the neighborhood in a long black robe. He had a huge bushy beard and dark wavy hair. He was all in the stereotype of a medieval monk. Then it happened. The church had a miracle, a bleeding painting, and people came from all over, crowded in a line down the sidewalk, eager to participate in an outpouring of the divine. One day, when I was home in Toronto, a woman stopped me on the street.

“Excuse me, can you tell me where the miracle is?”

I told her: two blocks east, one block north, and then you’ll see the line.

Now, what about 1977? The 15 years between 1977 and 1992 seemed, at the time, HUGE, but from the point of view of 2022, not so much. Life has these interior narrative arcs, doesn’t it? Little arcs that you don’t recognize at the time but seem wildly obvious in hindsight.

In the summer of 1977, as a family we visited Wingham, Ontario, where my father had worked at the television station, CKNX, between 1958-61, when it was a CBC affiliate, before he and a pal, Paul, took themselves to England in a spirit of wild adventure. Ostensibly, they went to attend the wedding of another Canadian pal, but then they stayed for years. It was where my parents met, at the London Hospital where they both worked, she in x-ray, he in photography. Various maneuvers occurred before they married in Upminster, Essex, in September 1964 and then moved to Toronto in 1965, where a house was purchased ($14,800) and children soon followed.

Wingham, of course, is the birthplace of Alice Munro, Canada’s literary Nobel laureate. Born in 1931, six years before my father, she left town in 1949 to attend the University of Western Ontario. In 1951, she moved to Vancouver with her husband.

I know we went to Wingham in 1977, because I remember visiting a shop where one of my father’s old pals worked, and he gave me (and probably my brother, too) a little silver-coloured “77” pendant on a chain. I had it for years and years, and it may still be around here somewhere in the bottom of some box. It’s the only trip to Wingham we ever took, as far as I can recall. We also visited Goderich on that trip, and for years I had in my desk a block of salt I picked up there. While he was in Wingham, my father was aged 21 to 24. He got his pilot’s license—recreationally. In the late-1970s he renewed this license and took me and my brother flying in rented Cessnas, before concluding it was a hobby too expensive for his budget.

The summer of 1977, I was eight, soon to be nine. It’s the age my stepdaughter was when her mother died. I think about that a lot, wondering what she will remember and how, over time, I might help her fill in the blanks. Her brother was one day short of being 12 when his mother died, so he has more memories, though he talks about them less. One story I think about is this:

As Kate approached the end of her life in 2012, we went to see a psychiatrist in the palliative care department at Princess Margaret Hospital. He asked her what her biggest worry was.

“My kids,” she said.

After establishing their ages, he replied that he had something that might offer a modicum of comfort.

“Based on what we now know about child development, by the time the child is seven years old, ninety per cent of the parent’s job is done. You’ve accomplished 9/10th of what you could do for them.”

Did that comfort her? If any, very little. What was done was done, and what would be would be.

Of course, for me—and these kids—we’re not done yet. And I can remind them that 9/10th is an awful lot. In my own case, was 9/10th really done by 1975? In that year, my mother was 34, my father 38. They seemed much older then, they’re younger than that now.

In my Saskatoon years, I was 23-25. When I returned to Ontario in 1994, my mother said, “I didn’t think you would ever come back.” This surprised me because I always intended to return. In 1963, the year she turned 22, my mother took herself to Canada. She met my father because she needed a passport photo. She went to the London Hospital photography department, and the dude who took her picture happened to be Canadian. For a big chunk of 1963, my British born mother was in Canada, and my Canadian born father was in England. I had been brought up with this story, and it seemed completely natural for me to “go away” in my early 20s with the full intention of “returning.”

In 1976, my mother took me and my brother to England for six weeks. I remember taking a boat down the Thames as we went to visit Greenwich and the Cutty Sark, which I later recreated in paints on an enormous piece of paper. I remember visiting the Tower of London and standing in a powerfully long line, held up so the guards could search each bag for explosives, as the IRA had an ongoing active bombing campaign. When I visited the Tower next, in 2014, I paused above a brass plaque in the armoury, which stated an IRA bomb had exploded on that spot in July 1974.

The sub-title of this piece says, “addressing the God thing,” but it’s not really that, is it? Or even about the “Green Bible,” about which I have less to say that I thought. Moses, Job, and Ezekiel are the three prophets I remember most if I were to say anything. Moses failed to achieve his dream. Job became the plaything of Yahweh and Satan—and was precursor to Kafka’s “K.” Ezekiel saw a wheel a rolling, away in the middle of the air. Magic.

I’ve never known how to accommodate this Mennonite stuff into the narrative of my life. If asked to define my cultural heritage, it would have to be a mix of Upper Canada settler Methodism mixed with atheistic-infused Northern Ireland Protestantism, filtered through post-World War II Englishness (e.g., Blitz Spirit) and Trudeau Senior 1970s multiculturalism. Or you can just say I’m a middle-class, urban-raised straight White male, shot through with 1980s pop culture. All of that is true, and all of that is insufficient.

The church has always been there, though, in one form or another. My mother worked for the church in the early 1980s as an “outreach worker.” She ran a toy lending library and mother support program at a public housing complex near O’Connor and Eglington. This led to a similar job in Regent Park, not funded by the church, which led to a program supporting mothers in the Beaches, except for that program the mothers didn’t come. They sent their nannies.

At various times, my father, my mother, and I all served on the board of directors of the seniors building, where I was a teenage janitor. In the early 2000s, when I was on the board, the institution found itself in conflict with the Government of Ontario, my employer, so I resigned. In the late 1990s, I was on the church council when a conflict consumed the congregation, and someone accused me of being influenced by Satan. “Not today, Satan.” MF.

When I married in 2007, I wasn’t attending church, and neither was my soon-to-be wife, but the Mennonite pastor agreed to marry us, and in 2012, he presided over her funeral. Faith in action. Later, the pastor would ask me if, in the hard months after my wife’s death, I felt something holding me up, an invisible force supporting me.

“No,” I said. “No, I haven’t.”

I do acknowledge, gratefully, however, that the church ladies organized the kitchen—and the cakes—for Kate’s funeral. (Where was the miracle? There was the miracle.)

My wife was raised Catholic, though her father had stopped attending Mass after Vatican II, and her mother had converted to Catholicism for her marriage. I once witnessed my wife explode in fury when she discovered that her mother had never once (“Not once!”) been to confession, yet she had sent her children to Catholic schools.

“We didn’t really care if it was Catholic or not. We just thought they had better discipline.”

My wife didn’t consider herself Christian, let alone Catholic. Christmas was about Santa Claus and turkey. Her father once administered her: “You don’t even tell the children it’s about the birth of Jesus.” No, and you don’t even go to Mass. Her rage at Rome was enormous. She told me she still felt shame about lining up in the school gymnasium to give confession to a priest who sat on a chair in the middle of the gym. She might have preferred the iron implements of torture.

In 1990, when I took a term off school and took a magazine writing class at what we’re now calling University X, I had to write a couple of “pitch” letters, proposing stories I would write to a presumed magazine editor. I pitched two stories: one was about growing up Mennonite in Toronto. My teacher thought this was a good story; it had potential; it had a “fish out of water” quality; it could show the familiar world through an unfamiliar frame. There was no way I was going to write that story. I could see how it could be interesting, but I didn’t see how I could write it.

The other story I pitched was about a volunteer assignment I’d taken on that summer. One night a week, I went to the Don Jail and sat with inmates as they worked through correspondence courses or literacy training. Many of the men I met there were being held indefinitely on immigration holds. I got the assignment because my mother knew one of the women who coordinated the volunteers. They had an office in the old 1800s Don Jail building—this was before it was renovated, but after it was used as a bar scene for a dancing Tom Cruise in Cocktail (1988). I took the training and followed her around one evening, before returning the following week on my own, standing in front of the large metal yellow doors and waiting to be buzzed in.

This is the story I drafted as the assignment for my magazine writing class. I interviewed the volunteer coordinator and patched together what I could. She told me they had to let one volunteer go, a young woman, because she refused to stop wearing tight, revealing clothing: “It’s just not fair to the guys.” I asked if she thought the educational courses would help the inmates. She didn’t hold out much hope for most of them.

“They don’t grow up with good role models,” I remember her saying.

I asked what she meant.

“When you don’t see your parents go out to work in the morning, you don’t get the idea that that is what you should be aspiring to. Most of these guys are here because they don’t know what else to do with themselves.”

I don’t know if I put that in my magazine assignment or not. It wasn’t the story I wanted to tell, because it didn’t say—we’re on a path towards a solution here. It was just, things are dark, and mostly they’re going to stay that way.

I aspired to a story with a happy ending. Faith in works, getting things done, all that David Copperfield kind of crap.

“Everybody knows the war is over. Everybody knows the good guys lost.”

ADDENDUM: My mother found the use of this video from “Jesus Christ Superstar” (1971) to be “disgusting.” I almost went with the video for Leonard Cohen’s “Everybody Knows” (1988), but I’d used a Cohen song in an earlier post. Besides, Herod swings and Christ is way bigger than that pimp lost in material decadence.

I also remembered that I appear on a list of “Mennonite writers,” but I wasn’t sure where I had seen that. I found it: Goshen College (USA). Also on this are Melanie Cameron and Carrie Snyder, both of whom were at the University of Waterloo during the time I was there. Greg Bechtel is on the list, too; we attended the same Toronto church and spent a summer as part of the staff of Fraser Lake Camp (1988). Greg also attended Waterloo while I was there. Maybe it doesn’t need to be said, but I’ll say it anyway; I don’t think the four of us, as writers, have anything in common.

Finally, in Spring 2001, I believe, I spoke to a class at the Canadian Mennonite Bible College (CMBC) in Winnipeg. My book Only a Lower Paradise (2000) features, well, Jesus—though the tone is somewhere between Vonnegut and Pynchon. I can’t remember how this came about, except I spent the 2000-01 winter on Pender Island in B.C., and in March or so 2001 I took a bus from Vancouver to Toronto, stopping along the way, giving readings from my “new” book to tiny (!) audiences. One of the CMBC students asked if my book was a “Christian book.” I hummed and hawed, thinking I can’t just say, “No.” I mean, I was at CMBC! But also I didn’t want to explain how I thought, basically, there was no such thing. So, I just said, “Yes, sort of.”

SECOND ADDENDUM: I added the bit about the family picnic.

I’d also like to note Uberto Eco’s 1994 insight on the difference between Macs and PCs. Let us compare mythologies.

The fact is that the world is divided between users of the Macintosh computer and users of MS-DOS compatible computers. I am firmly of the opinion that the Macintosh is Catholic and that DOS is Protestant.

Indeed, the Macintosh is counterreformist and has been influenced by the “ratio studiorum” of the Jesuits. It is cheerful, friendly, conciliatory, it tells the faithful how they must proceed step by step to reach – if not the Kingdom of Heaven – the moment in which their document is printed. It is catechistic: the essence of revelation is dealt with via simple formulae and sumptuous icons. Everyone has a right to salvation.

DOS is Protestant, or even Calvinistic. It allows free interpretation of scripture, demands difficult personal decisions, imposes a subtle hermeneutics upon the user, and takes for granted the idea that not all can reach salvation. To make the system work you need to interpret the program yourself: a long way from the baroque community of revelers, the user is closed within the loneliness of his own inner torment.

You're beginning to come into focus for me. This one is amazing. You certainly did finally figure out how to work the Mennonites into the story.