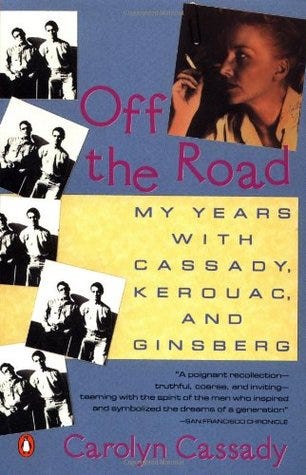

Memory is a funny thing. I remember seeing Carolyn Cassady at the Harbourfront Centre in Toronto, Brigantine Room. I would have guessed it was the mid-1990s, but I found no evidence online that she was there then. The online evidence suggests the event happened in 1990, which is the year her book Off the Road: My Years with Cassady, Kerouac, and Ginsberg was published. Makes sense.

Here’s a blog by Rick McGinnis with photographs of Cassady in Toronto (1990) and memories of the event similar to what I will say below.

McGinnis’s photographs are dated October 1990, so I guess that’s when the reading was. That fall I was doing … not very much. I was taking a term off from my undergraduate program, which I had started in 1987. I was halfway done and not super enthusiastic about it. In the summer of 1990, I had worked at the Ontario Ministry of Transportation, sharing a cubicle in a Soviet-styled brick building beside Highway 401 in the north-west corner of Toronto. I was bunking with my parents in the south-east corner of Toronto, so the commute by subway-subway-bus, then by bus-subway-subway to return, kept me in transit up to three hours a day.

I hated this job with a roaring passion. I took it for two reasons: I wanted to be in Toronto and they accepted me. But it was a terrible fit for both of us. They had hired two English majors, a junior student and a senior student. I was the senior student. Our area handled “publications,” which had sounded—initially—potentially interesting. But the larger organization was populated with engineers, who conducted studies and then wrote reports. The publications people assembled the reports, “edited” them, published them, and maintained a library of them. One of the jobs of the students was to respond to requests for these reports, which—surprisingly (?)—came from around the world.

Ontario engineers were apparently international experts in things like the composition of asphalt in winter conditions. One study I specifically remember reviewed the paint used for the lines down the middle of highways. Somebody tell Joni Mitchell. If you see a series on lines painted across a lane on the highway, and you think, “What the heck?”, you can now answer yourself: engineering study.

That summer I also took a course called “Media Writing,” a night class at Ryerson. It was part of the Radio and Television Arts program, preparing students for radio/TV writing, and it had a huge influence on me. I had become an English major, in part, because I “wanted to be a writer.” I had no real idea what that meant, except since the earliest days of my life I had loved books, though in junior high and high school I had been a visual arts person. My maternal grandfather had been a graphic designer, and I loved to draw and paint. But I didn’t consider myself a painter, I considered myself an Artist. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, except I knew that I wanted to create. I wanted—needed—a life that engaged my imagination.

As my high school years wound down, I didn’t see myself attending art college, so I decided to study English instead. It seemed the most “creative” of the university options. But halfway through my undergraduate degree I was not feeling the creative vibe. I had been forced to take courses in accounting and economics, computer studies and linguistics. None of these excited me. I approached each with resignation. “I guess this is what I need to do to get to the stuff that I will really like.”

But what was that? And when was it going to happen?

“Media Writing” connected me to the creativity of language in a way I had been sorely missing. Over the course of the term, the teacher taught us to write a good sentence. Truly. She went over the basics in a manner that has stuck with me. Active/passive voice. Strong/weak verbs. Simple/complex structure. The history of the English language; it’s Anglo and Saxon components; and its ability to integrate “foreign” words and concepts. Most of this was not new to me, but this course pulled all the bits together like I hadn’t managed before. One exercise required us to mimic authors, that is, take a sentence and write the same sentence using different words. Same rhythm, same beats, same punctuation. I did a sentence from Margaret Lawrence. It was tough—and revealing. Every word, every beat was a choice.

I brought a piece of my Ministry of Transportation work to the teacher. I had to write short summaries of the engineering reports, like 100-word abstracts. I gave a couple pages to the teacher for comment—and she schooled me. I was amazed by how she found words to remove and edits to make each summary almost like a prose poem. There was Art at MTO, after all.

I thought maybe I should get out of my English undergrad and into a journalism program—or into the Radio and Television Arts program. I discussed that with my Ryerson teacher, and she said what so many of these creative industry profs have said to me. “It’s a hard industry to get into and tough to survive in.” That summer, the CBC had laid off dozens, maybe hundreds, and was shifting from having employees to working with freelancers and independent production companies. These options weren’t immediately appealing. I decided not to go back to the University of Waterloo that fall—and also to do not much else.

I signed up for another Ryerson night class, though, “Magazine Writing,” taught by DH, whom I ran into two years later in Saskatoon, where he was researching a book on the Martensville … what should I call it? The Fake Satanic Cult? I don’t think that book ever appeared. Inspired by “Media Writing,” I thought maybe I could turn to magazines for freelance work. DH shared pitch letters and got us to read Tom Wolfe on The New Journalism, an essay that had first appeared in Esquire in 1972. It was old then; it’s really old now.

While I enjoyed “Magazine Writing,” I discovered I didn’t want to be tied to facts; I wanted to live in the imagination. I wanted to create something out of nothing, like the poems I had been writing in my free time at MTO. Actually, by the time my term at MTO ended, I think I was mostly writing poetry and ignoring my other duties. I didn’t get a good performance review for that co-op posting, and I didn’t care. I never wanted to do anything like that ever again, though—well, that’s for another time.

One historical record from that summer that involved me, was an instructional movie MTO made with the OPP around drinking and driving. They needed someone to drive a car, wobbling it down a stretch of rural road, while it was “chased” by an OPP cruising and pulled over. I drove the car and we did several takes. I had a walkie-talkie on the passenger chair, so the police could communicate with me. In one take, I wobbled over the yellow line as another car approached. Just a little. The OPP barked at me: “Don’t do that!”

We were a small group in the publication’s unit. My supervisor was a young woman not much older than me, probably in her late 20s and stereotypically feminine. She came in made up and frilly and went on long lunch dates with one of the hunky engineers. It seems to me that she was married, but not to him. The manager/director of the unit was a small weaselly dude with a Walter Mitty complex. In appearance, he was a nerd’s nerd, yet he wore mirrored glasses and drove a sports car. His hyper masculinity was all symbols and cliché.

I remember recommending On the Road to one of the young engineering dudes who worked across the hall. We used to congregate in the hall daily as the snack cart came around mid-morning and mid-afternoon, following a track that was articulated somehow into the floor. Yes, very Mad Men, I know. It was like a vending machine on wheels. It had a programmed route and it stopped in the hall outside our door, beeped, and everyone would pour into the hallway, pick up snacks or coffee, and drop their money in the box.

I tried to find a photograph of this thing online, but I struck out. Trust me. It happened. And this MTO job, this automated snack cart thing, is the perfect foil for the Beat’s HOWL against mid-century America, is it not? That hollowness that also inspired Flower Power and led to, well, whatever fragments of it are left today. Perhaps something more consequential, like Malala and Greta.

Anyway, I loaned On the Road to this engineering dude, who was chatty, curious, read books, etc.

“I don’t see what you are talking about,” was his response. “I don’t see how this is a different type of writing, how this is a new way of seeing things.”

He didn’t really like it at all, but he attempted it. I’ll give him that. He may well have been right.

I seem to have no photographs of myself from the summer or fall of 1990, otherwise I would include them here.

And, thus, we return to Carolyn Cassady.

She read at Harbourfont Centre, October 1990. Wikipedia provides this summary:

Carolyn Elizabeth Robinson Cassady (April 28, 1923 – September 20, 2013) was an American writer and associated with the Beat Generation through her marriage to Neal Cassady and her friendships with Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and other prominent Beat figures. She became a frequent character in the works of Jack Kerouac (pulled February 27, 2022).

My memories of the Cassady event are blurred with my memories of reading her book, which I did years later. I think I took it out of the library during my Saskatoon years (1992-94).

As noted in my post, Ottawa (1989), my cousin introduced me to the Beats that fall, loaning me three Jack Kerouac novels: On the Road, The Dharma Bums, and The Subterraneans. Like every young (mostly male, mostly White) person who has developed a minor or major obsession with Jack Kerouac, I did so because I felt something expressed in these novels that I hadn’t felt expressed elsewhere, and it was exactly what I was missing and needing at that moment. The lyricism, the questing for meaning, the articulation of emptiness and the need to fill it with joy, with fun, with just about anything except the thing that was expected.

Yes, and it wasn’t only because I was a writer and needed new experiences that I wanted to know Dean more, and because my life hanging around the campus had reached the completion of its cycle and was stultified, but because … somewhere along the line I knew there would be girls, visions, everything; somewhere along the line the pearl would be handed to me.

I certainly wasn’t finding any pearls at MTO—and my undergraduate degree was largely, to borrow Kerouac’s word, “stultifying.” I was accumulating experiences, but not experiencing breakthroughs. That fall, I was in love and locked out. This was a love unlike anything I had ever experienced, and I thought it just had to, just had to work out, but it didn’t. The first two sentences in On the Road:

I first met Dean not long after me and my wife split up. I had just gotten over a serious illness that I won’t bother to talk about, except that it had something to do with the miserably weary split-up and my feeling that everything was dead.

So, there was that.

In high school, I had a weekend job as a janitor at the local seniors’ complex. At loose ends in the fall of 1990, I visited my old boss and asked if they needed anyone. They did as they were expecting a government inspector to come through soon, and they had work that they needed done. They hired me on, temporarily. One of the other janitors was a Filipino man, aged 70, who did everything I did, pushing mops, etc., and probably more.

“You’re 70?” I asked.

He looked nowhere near it. In 2022, he’d be 102.

“I never stopped working,” he said. “I never got out of shape.”

That centre had a small nursing home attached, and a couple of times a day we janitors would mop around the beds. There was an alarm system to keep the residents in. That fall, one of the women kept taking her clothes off and wandering around naked. The nurses would corral her and dress her, but sometimes it took time.

My Filipino friend said, “One time they found her in bed with one of the other residents.”

He pointed him out. “That one.”

One of my tasks was to work in the laundry. So much laundry! Sourced from the nursing home. Pounds and pounds of shit-stained sheets. My partner in the laundry was a middle-aged (I’m going to guess) Polish woman. She couldn’t believe her luck, having a 22-year-old dude slugging shit with her. I say middle-aged; she could have been anywhere between 40 and 60. She didn’t think I would survive the job, but every day I came back. She gossiped the hours away; I don’t remember any of it. Writing this now I think, yes, MTO was a shit job, but here was a job with actual shit.

Kerouac went on the road, looking for experience; I found it closer to home.

What did the Beats mean to me, really?

There was that, yes, the Flintstones. And also, somehow, the Beatniks had become the hippies. The 1950s had become the 1960s. And the Sixties, that’s where it all happened, everything of consequence, everything I needed to unpack before I could figure out what to do next. Or more dramatically, before I knew what to do with my life. Right?

Somewhere along the line I knew there would be girls, visions, everything; somewhere along the line the pearl would be handed to me.

I’m going to cut to the chase and say I’m kind of an anti-Beat now. This questing for the pearl, this chase for breakthrough, strikes me now as a chase for oblivion. A suicidal mission, really, connected to addiction. These conclusions began to take shape on the night I saw Carolyn Cassady at Harbourfront Centre, October 1990, and they took a long time to sort out and take hold—but take hold they have.

Thank you, Carolyn.

She read from prepared remarks and had a commanding presence, a kind of moral charisma that I have seen in only a very, very few others. I think her book is as profound as Kerouac’s—and more honest.

She was a conventional young woman before she met Neal Cassady, model for Kerouac’s character, Dean Moriarty, and she was swept up in her early 20s into a storm that would carry on until the end of her life at 90 in 2013. She was the wife of “Superman,” as Ken Kesey called him. Whatever. Neal is more myth than human, most of the time, and Carolyn took on the impossible. Making the mythological, real.

She worked as a theatre set designer in California. In On the Road, the narrator goes coast to coast to coast with Dean, who has women and men here, there, and everywhere. He is insatiable, of body and mind. What should he choose? Wife and child on the east coast? Wife and child on the west coast? (I can’t remember how many children exactly!)

At one point, Neal ends up in jail and he wants Carolyn to mortgage the house to get him out. She refuses and that’s a betrayal too far for him, but she doesn’t regret it. It is her home, the home for her children. He dies on a train track in Mexico, February 1968, aged 41—after having been the driver of Kesey’s bus, Furthur, and featured prominently in another book, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe, an example of his fabled New Journalism. Kerouac died in October 1969, aged 47.

Cassady said Neal and Jack were suicidal, but also had been raised Catholic. She said it plainly; their Catholicism stopped them from implementing direct self-murder. Instead, they lived lives with big risks, without boundaries, because they couldn’t settle, couldn’t accommodate living, and also wouldn’t snuff themselves. I believe one of the stories Carolyn told was how Neal could flip over a Volksvagen Beetle. Why? Because he could. It was performance, yes, but also because his sense of risk was absent. He lived on the edge, pushing towards oblivion.

She had an affair with Jack, too, because Neal encouraged it, suggested it.

Later, to support a movie being made about Jack and Neal, she shared family paraphernalia—to help the production understand its material and make it real. When the shooting was over, her stuff was not returned to her.

McGinnis has a nice summary:

Cassady insisted till the end that her husband was much happier as paterfamilias, working and paying off the mortgage on their suburban home and raising his children. His tragedy was that his chaotic upbringing left him unable to manage that apparently banal task without lurching off for months or years, eventually turning into a "trained bear" performing his Dean Moriarty act for Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters, a role that predictably destroyed him. Her tragedy was that she set her mind on making him the man in her life, a poor decision that ended in regret, alone in his shadow for decades after he flamed out.

The ending of Carolyn’s book affected me deeply. It’s something I often remember, a twist as powerful as the Gospels. She was getting phone calls from Neal’s east-coast “wife,” even after he was dead. They were two women in competition, and Carolyn hated her, and then she didn’t.

And then a strange thing happened to me. Right in the heat of my rage, it was as though I heard a click somewhere inside me, and with no pause or change in my angry tone, I went right on yelling at her, but now—I suddenly love her! I began to feel warm, melting and joyous, and I listened to my words in awe. ‘Now, lookit, Diana—life is to live—you’re a young woman still—yes, you are,’ as she started to object. ‘God gave you life, not age, an you’re attractive—you used to be a model, remember? Well, remember things like that—let the dead past die. Life can be so great, Diana—come on, now, quit all your moaning, complaining and looking back—get out there and use your brains and good looks. You’ve been blessed by knowing Neal—use the gift he gave you—for good! For living!”

*

Unrelated to Carolyn, some brainstormed thoughts on the Beats.

In 1996 (probably), Roddy Doyle read at Convocation Hall, University of Toronto, to a packed audience. I went with my parents. Doyle was touring his most recent book, The Woman Who Walked into Doors. I believe he was interviewed onstage and possibly took a Q&A from the audience. Anyway, in one of his responses he said he hadn’t read that much American literature, but he was trying to catch up. He’d recently read On the Road, and, gosh, wasn’t it just shite?

Oh, I thought. I could see it wouldn’t be his kind of book. Too dreamy. Too sentimental. Lacking grit. Lacking a true confrontation with certain realities.

But isn’t that America? The country that facilitates the easy running away, the simple starting over?

I remember reading a David Mamet essay, possibly in Make Believe Town (1997), where he said he admired Kerouac’s Maggie Cassidy (1959), but really nothing else. The novel he admired was straight simple reporting without the Beat mythological crap.

I had a roommate at university who introduced me to Tom Waits. He didn’t like Kerouac, but he played me Jack & Neal from Foreign Affairs (1977). There’s the myth, content and form.

In the late 1990s I reviewed a “Beat Generation” CD-ROM (OMG, remember those?), possibly for Shift magazine. It had a remarkable collection of video clips and archival content, and I wish I still had it.

Post 1989, I read more Kerouac, including his final novel, Vanity of Duluoz (1968). If Doyle thought On the Road was shit, he would have to dig deeper for the foul fragrance that is this dispirited work of alcoholic ramblings. There is no quest for the pearl here, only depressive memories and heavy ego. Sad doesn’t even begin to define it.

It strikes me now that if Kerouac had access to statins and by-pass surgery, he might have avoided an early death and made the transition to a late-stage writer. Could he have come to a new accommodation with the world? Did he ever come to an accommodation with the world? We’re fond of saying, it’s the journey not the destination, but if all you do is journey (on the road) can you ever absorb the wisdom of stillness? And at base, maybe this is Kerouac’s enduring core: his spiritual seeking. I’m not qualified to say how valuable and lasting his attempts at Buddhism were, or remain, but I have no doubt that they were legitimately held and engaged.

The footage of Kerouac supporting the Vietnam War and complaining about hippies with William F. Buckley Junior is what it is.

#sad #heartbreaking #confirmationbias

In the summer of 1992, I took a week-long fiction writing workshop with Barbara Gowdy. She said, “Everyone’s trying to write like Kerouac.” I sort of was, still, but I was shifting to write more like Ray Carver. (More on that another time.) I remember saying to Barbara, “It doesn’t go anywhere—it goes to Vanity of Duluoz, which is nowhere.” I liked the Buddhists in The Dharma Bums, though. “Life is suffering.” That was the insight, but what to do with it? Not everyone can disappear into the woods and watch for forest fires.

In 2001, I had occasion to ask Russell Banks a question about a screenplay adaptation of On the Road he was working on. He appeared at Harbourfront Centre in Toronto, supporting the release of his collection of short fiction, The Angel on the Roof (2001). In the biography of Russell in the program, it noted he was working on the screenplay, so I thought it was fair game. I asked him something along the lines of, “What did you learn about the novel by adapting it into a different medium, since so much of what’s admired about the novel is the gratuitous prose?”

He said, “At the core, it’s a story of friendship. The challenge is stripping away the mythology to show them as real people.”

I think Carolyn would agree.

And what about Ginsberg and Burroughs?

I remember reading a magazine article about them in the 1990s, and Burroughs said something about God, and Ginsberg said, “I didn’t think you believed in God,” and Burroughs replied, “I’ve always believed in God.” He might have even said something like, “It’s at the centre of everything I do.” I clipped that out, and that clipping may still exist somewhere. Only God knows where.

William S. Burroughs never meant anything to me until I saw Laurie Anderson’s movie, Home of the Brave (1986), which fills the screen at one point with a quotation from Burroughs: “Language is a virus from outer space.”

Now that interested me.

Tony Burgess later took the idea further in Pontypool Changes Everything (1995) and later adapted into a film (2008). Goodreads: "Pontypool Changes Everything depicts ... the compelling, terrifying story of a devastating virus. You catch it through conversation, and once it has you, it leads you on a strange journey - into another world where the undead chase you down the streets of the smallest towns and largest cities."

Gowdy recommended to me Burroughs’s Interzone (1990), a collection of short pieces that “chronicles William Burroughs’s transformation from apprentice to full-fledged writer,” so says the back cover.

That’s what Barbara said, too: “You can see his growth as a writer.”

I was grateful for this, for I was wondering, how does one get better?

When I think about Burroughs, I think about Cronenberg’s adaptation of Naked Lunch (1991) and also The Sheltering Sky by Paul Bowles (1949). Now Bowles was a pre-Beat, and so a Beat influence. I don’t think I caught up with Bowles until I saw the documentary, The Complete Outsider (1995), which is available on YouTube. I read The Sheltering Sky after seeing the movie, though I am told Jane Bowles is more interesting. Perhaps this year will be her year.

Cronenberg’s depiction of “the Kerouac character” is hilarious.

Over time, it seems that the influence of Burroughs may be the widest of the Beats. It is surely the most diverse. In 2020, in an interview on the WTF podcast, Patti Smith spoke about her friendship with Burroughs in the 1970s. She thought he was cute, and he said, “You know Patti, I’m a homosexual.” Drawl it out in Burroughsese. She really loved him. See also the earlier reference to Laurie Anderson.

See Burroughs and the 1970s New York art scene.

And, finally, Ginsberg.

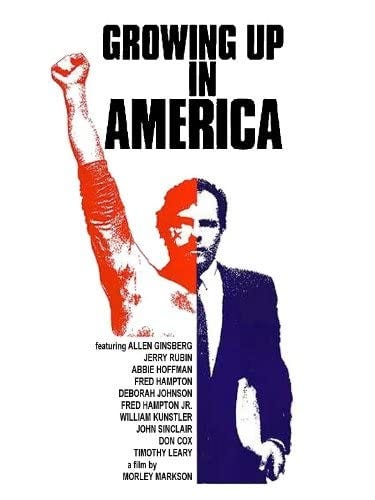

I know I started by saying my cousin introduced me to the Beats in fall 1989, but maybe that was only Kerouac. I think what first introduced me to Ginsberg was the film, Growing Up in America (1989). The IMDb site says the film was released April 1989. I saw it at the Bloor Cinema in Toronto, but it was while I was in the middle of a school term at the University of Waterloo, and it was the middle of the week. I took a bus from Kitchener to Toronto specifically to see this film. In the summer of 1989, I was attending classes, so I think that’s when I saw it. I later bought a copy of the movie poster, which I still have.

This film—available on YouTube—includes two sets of interviews with so-called Sixties radicals. One set is from a 1971 documentary, and the second set is from the 1980s. It is fascinating, and I’ll have more to say about the Sixties and its radicals some other time.

I bought a copy of Howl (1956) in the University of Waterloo bookstore, probably that summer, and read it. Or parts of it. Does anyone really need to know more than the famous line about the “best minds of my generation,” which surely influenced The Who?

Later, I bought a copy of interviews with Ginsberg and read it randomly back and forth.

In November 1996, Ginsberg spoke at Convocation Hall, University of Toronto. I didn’t go. I don’t think I heard about it until it was sold out, but I was okay with that. Macleans did an article about it (Nov. 11, 1996). NOW put Ginsberg on the cover (Nov. 14, 1996, scroll to page 36 for the story). U of T’s The Varsity student paper wrote it up: “Ginsberg returns with youthful fervour” (Nov. 18, 1996). But not too youthful; he died less than six months later (April 5, 1997).

I read another account of the event, but I can’t remember where. What I remember, is that Ginsberg was cranky. Along the lines of “kids today, they don’t know…” Don’t know what? That it’s not really about “first word best word.” That it (writing well) is about knowing the technical stuff. That the Beats did know their technical stuff, it wasn’t about making it up as you went along. You won’t find anything like that in the articles I linked to above. Maybe I’m remembering it wrong, but I don’t think so. Maybe it was just a small moment, a small exchange, a minor quotation, but it’s what I remember.

In the NOW article, the journalist asks Ginsberg how he feels about the fact that Bob Dylan had recently given permission to use “The Times They Are A-Changin’” in a bank commercial. Ginsberg replies that he himself appeared in a GAP commercial—though he later gave away all income from that project because of the company’s use of sweatshops. “To live outside the law you must be honest,” Dylan sang on Blonde on Blonde (1966), and Ginsberg celebrates this insight in the liner notes for Dylan’s Desire (1976).

Does anyone think of Uncle Allen now? I’m not sure.

Was Barbara Gowdy right that everyone tries to write like Kerouac? Heard of autofiction?

Have novelists stopped making things up?

No, but also, yes.

Alternately, yes, but also, no.

“Fail better,” said Beckett, who was definitely not a Beat.

*

Finally, are the Beats even a thing anymore? What’s the latest on that?

I don’t know. I’m not sure I care.

Since we started with Carolyn Cassady, let’s also note renewed focused on the women of the Beat generation. Joyce Johnson’s memoir, Minor Characters (1983), is apparently great (I haven’t read it). The book won the National Book Circle Critics award and documented the years 1957-58 when she dated Kerouac, On the Road was published, and Johnson witnessed Kerouac suffer a major depression.

From where I sit now, these depressions seem more interesting than the lyricism of the road, frankly. Is Knausgaard Kerouac’s heir?

Addendum: The summer of 1990 (and into the fall) I volunteered at the Don Jail weekly. I arrived back in Toronto in April that year, ahead of my summer job, and I wanted to “get involved in something.” My mother knew one of the volunteer coordinators at the Don Jail, so I reached out to her. They had an office in the old 1800s Don Jail building—this was before it was renovated, but after it was used as a bar scene for a dancing Tom Cruise in Cocktail (1988).

Many inmates took advantage of their time inside to take educational courses. Volunteers went in and assisted with homework or tutoring. I went once a week for a couple of hours, saw two different inmates. I had some repeat customers, but mostly it was new folks every time. The night I went for my orientation, following some classroom training, I followed along with the volunteer coordinator my mother knew. One individual we met I will never forget. We sat and discussed their educational options. What did they want to focus on, this time?

After I was alone again with the volunteer coordinator, she said to me: “She wasn’t sure last time which was she was going to go.” The jail didn’t recognize her as a “she,” and as she went back into the general population, I heard someone hell, “Hey, the bitch is back.” I find that terrifying every time I think of it. That whole scenario. I never saw her again.

Many of my learners were not taking courses, they were learning to read, except for one guy—an Italian—who was a highly proficient reader, just not in English. I gave him something to read, and he sounded out the words. One was “lettuce,” which he pronounced with confidence. LE-TWO-CHAY. I had to laugh.

“No.”

“No?”

“LET-US.”

“LET-US?”

I nodded, but I said: “LE-TWO-CHAY is way better, though.”

Just great. I like the quick pace and the way you orchestrate (rope in) cleaning shitty sheets, failed romance, lunch carts, Kerouac, and, well, everything. A structure that is loose and tight at the same time. Quite remarkable. But especially the pace. You make life and literature exciting. More of this.