Reviews of some books I've read recently.

In the Margins: On the Pleasures of Reading and Writing by Elena Ferrante (2021)

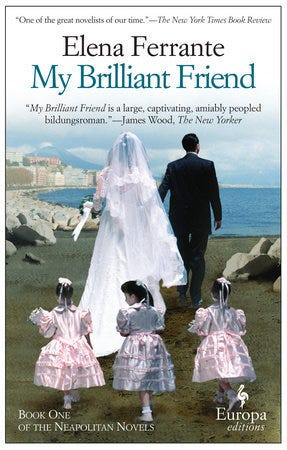

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante (2011)

The Magician by Colm Toibin (2021)

Silas Marner: The Weaver of Raveloe by George Eliot (1861)

I've heard a lot about Elena Ferrante in recent years, and what a pleasure it was to finally read her work. I didn't know where to start, but I heard good things about her slim collection of essays/remarks about writing, In the Margins, so I chose to begin with that, and I'm glad I did. Why? Because she states clearly her interests and reflects on her approach to writing. Specifically, she confesses an early obsession with wanting to be able to recreate reality through words and then realizing the difficulty, the impossibility, of doing that, and how that desire remains, as a source of tension, which opens up opportunities for the writing to work as writing.

Here we might turn again to the T.S. Eliot quotation that Hunter S. Thompson was so fond of. "Between the real and the ideal falls the shadow." Ferrante notes she sought the real, discovered the ideal, and discusses the revealed space in between.

In one interesting passage she says she learned from Gertrude Stein's The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933) how to imbed one story within another. A better way of putting it might be, how to appear to be telling one story while actually telling another. The Autobiography, written by Stein, is obviously on the face of it not an autobiography. Though Alice B. Toklas was a real person, Stein's partner, she is not the author of the autobiography, though it is written in the first person and tells the facts of her life. What it also tells are the facts (and interpretations) of Stein's life. It tells the story (a story) of Stein's life through the framework of a fictionalized (though real) telling of the life of Alice.

Ferrante finds in Stein's approach an escape from the obsession to capture reality in words. Reality is captured, but it's also caught in the prism of language, self-conscious its own creation. With this insight fresh in mind, I listened to the audiobook of My Brilliant Friend, the first of Ferrante's Neapolitan Quartet, which had been described to me as "not the best of her books." However, I found it incredible. On the surface, slow and conventional, yet it unfolds with deep intelligence, and there is a sub-plot: the act and product of writing, language itself.

My Brilliant Friend's first person narrator, Elena Greco, tells the story of her friendship in childhood with Raffaella "Lila" Cerullo. The story opens, however, with a framing device that is never closed. The narrator is an older woman. She learns that her childhood friend has disappeared. She returns to the beginning, and the story of their childhood unfolds. But it is also the story of Elena's relationship with writing, an act she excels at, but she knows Lila is better. But Lila only produces a few early works, then falls silent.

The book tells the story of their poor neighbourhood, the boys who were their peers, the conflicts in the streets, the inherited history, and their common struggles to find their way(s). It could be read as a coming of age story, and it is, but what Ferrante achieves is highlighted as her life-long interest in In the Margins — the challenge of establishing "women's writing" — as she tells a familiar story of children maturing to become adults with a sharp focus on the pressures that shape the girls. That is, how language and storytelling is both emancipating and restricting. Lila turns away from her academic brilliance, enabling Elena to shine in that area, while Elena sees her success arising from the influence of her remarkable spirited friend, who accepts limitations (such as an early marriage that come with wealth) as a different kind of freedom.

In The Magician, Colm Toibin reconstructs the life of Thomas Mann (1875-1955), German novelist, Nobel Prize winner.

I would call this a novel, not a biography. Maybe a biographic novel? The general facts are correct, but Toibin creates a lot as well. Also, this is an ensemble piece. Herr Mann is the protagonist, yes, but Toibin shows Mann in the context of his family life, beginning with his early competition with his artistically inclined brother and following through to the adventures and challenges of his remarkable children.

Michael Peterman in the Peterborough Examiner (Nov 19, 2022) calls it a "must-read."

...it takes us into the German experience of two world wars even as it dramatizes the complexities of Thomas Mann’s life. It is a view that we know too little about.

...

Born and raised in Lubeck, Germany but later adopting Munich as his writing home, Mann enjoyed a quick rise to early literary success in Germany under the Kaiser whom he supported during First World War. He remained a solid German burgher in spirit until the emergence of Hitler’s Nazi regime in the early 1930s.

“The year after his Nobel Prize, the Nazis got six and a half million votes compared to eight hundred thousand just two years earlier. But their support, he believed, could dissolve as easily as it had surged.” So writes Toibin of this critical period in Mann’s literary life.

However, finding himself a few months later shouted down in Berlin by loud fascist voices as he delivered a lecture ironically titled “An Appeal to Reason,” he realized that his views were an anathema to Hitler’s powerful party. Deeply disturbed by the spectacle of fascism on the rise, Mann famously chose exile from Germany in 1933; then in 1936 the Hitler government deprived him of his German citizenship.

Thereafter he lived in comfort but unease in Switzerland, then Princeton, New Jersey and Santa Monica, California. Returning to Europe, he died in Switzerland.

It wasn't until recent years that I started to read Mann. I listened to the audio book (25 hours!) of The Magic Mountain (1924) and recently did the same for Death in Venice and Other Tales (1912).

As a reader, I respond the seriousness of Mann's work, the depth of feeling, the conflicted characters, the broad scale of ambition, placing the action within historical context. One interesting sub-plot that Toibin develops is the contrast between the Mann brothers. They both write, but Thomas is far more successful. He is also far more conservative. Remote from politics early in life, he is drawn in deeper and deeper as German nationalism becomes homicidal. His brother, Heinrich, however, is attuned to the reactionary risks far, far sooner. We would say he was correct earlier, but he also suffers harsher consequences.

I found the swirling worlds of Mann's children deeply interesting. Erica and Klaus, the two eldest, are extremely spirited, establishing creative careers for themselves in between the World Wars, comfortable with their homosexual identities. The rise of the Nazis, however, darkens their prospects. Erica married W.H. Auden, marriage of protection to allow her to remain in England, and Klaus joined the U.S. Army, writing for the newspaper “Stars and Stripes.” Their playful early lives are wreaked by the forces of history, even as they escape the battlefields of Europe.

What a difficult lives to summarize, all of them!

Finally, a short look at George Elliot's Silas Marner: The Weaver of Raveloe. I read Middlemarch (1871) in recent years and committed to consuming more Eliot, especially after visiting Nuneaton, Eliot's home town, in 2017.

I did no research on Silas Marner. It was a novel I'd heard about, but that was all. It's a lovely short book, full of deft touches and surprising twists. Kyle Pruett, Clinical Professor in the Child Study Center at Yale School of Medicine, summarizes the plot thus:

Through a series of Edwardian twists and turns, [Silas] winds up taking in a child he finds wandering in the woods whose mother has died. He takes the child in because it’s winter and it’s the human thing to do. The child begins to affect him and really humanise him. There are a lot of other twists and turns, but those aren’t the parts of the book that interest me. I think it’s an interesting message. A child can evoke nurturing behaviour from men to whom they are not biologically related as long as the needs of the child are valued by the man.

It's funny, really; I hadn't expected this to be a book about intentional fathering. Single parenting, also. Silas is hard done by early in the book. He is lonely, hard-working, victimized by cheating and then by theft, impoverished but coping. A parallel story features shenanigans of the local middle class. Not aristocrats, but those with excess money from land owning.

The storylines cross the figure of a child, a girl whose mother is secretly married to a local young man, who has kept the marriage secret, as the mother is low born, a drug addict, socially "unsuitable." The mother trudges through the snow to confront her wayward husband, but she dies outside Marner's hut, and he takes in the infant girl as his own, raising her, loving her, earning the title of father.

No need to give away the ending, which of course is satisfying. As an intentional father myself, a step-father, who inherited two children and an ex-husband upon the death of my wife in 2012, I was not surprised that Silas knew how to nurture, or that he wanted to, or that the neighbours tut-tutted but largely supported him.

Love is patient and kind, and it is also active and life-altering, if you let it in. Eliot's novel packs a lot into its brief pages: social mores, moral conflicts, cowardice, caprice, historical pressures, plain old English common sense. I wonder if Orwell wrote about Silas Marner. It seems to anticipate him.

You've made me want to read Silas Marner.

Take Care.

Terry