Two recent book reviews for the Miramichi Reader:

Pieces of Myself: Fragments of an Autobiography by Keith Garebian (2023)

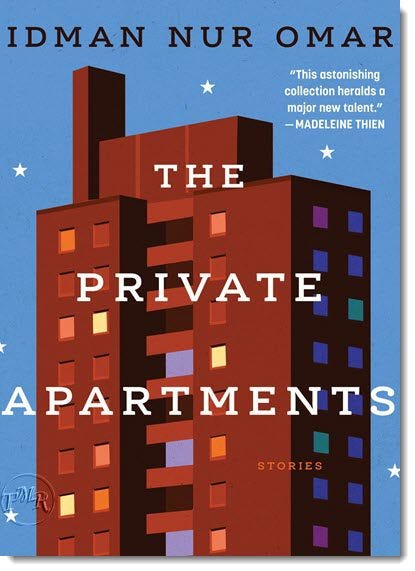

Private Apartments by Idman Nur Omar (2023)

Reflections on two other titles:

The Book of Negroes by Lawrence Hill (2007) [In the United States, Australia and New Zealand, the novel was published under the title Someone Knows My Name. See author's note on the title (Wikipedia)]

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers (2021)

For the longest time, I haven't been keen on historical novels, though in recent years I have been reading them more and more. What didn't I like about them? The tendency to earnestness, maybe. The primacy of historical sweep over literary style. The grounding in pedantic topicality. What did I prefer instead? Engagement with the contemporary. Self-conscious deconstruction of narrative. The individual's quest for meaning within an absurd, probably broken, world.

What has changed? In short, I can no longer sustain this dichotomy. It seems ridiculous now. Like life/art, history/literature seem forever blended. How did I ever think otherwise? Whatever dreamy end of history liberalism took hold of me thirty years ago, suggesting the past can be released, is now a faded mist. History pulsed hard again, its patterns never gone, now reanimated it seems (ironically, surely, and among other trends) by social media's ability to boost identities and us-against-them tribalism. It was a privilege to believe that history had gone, of course. For many the dreaminess never existed. I'm coming to terms with that, I think, though I'm unclear on my own description of it.

Is this too abstract? Perhaps so. So, the books, the books (both listened to as audio files).

It's taken me a while to get to this 2007 Lawrence Hill thumper. It's been on my extended short list ever since it came out. I wasn't keen on historical novels, but now I'm gung-ho. This is a good one, and what criticism of it can I muster? Not a word, I'm sure. Have you read it? I've asked many since. If not, give it a go. It is an epic.

The main character is Aminata Diallo, the daughter of a jeweler and a midwife, who is kidnapped at the age of 11 from West Africa. She is taken to the American south where she lives enslaved. It is the mid-1700s. Later, she is taken to New York City, where she escapes. The Revolutionary War breaks out. She is at risk of being returned to slavery, but she manages to evacuate to the British colony of Nova Scotia. This migration is where the title is taken from, as Hill has noted (Wikipedia):

I used The Book of Negroes as the title for my novel, in Canada, because it derives from a historical document of the same name kept by British naval officers at the tail end of the American Revolutionary War. It documents the 3,000 blacks who had served the King in the war and were fleeing Manhattan for Canada in 1783. Unless you were in The Book of Negroes, you couldn't escape to Canada. My character, an African woman named Aminata Diallo whose story is based on this history, has to get into the book before she gets out.

Nova Scotia is far from Diallo's final destination, however. She returns to Africa and then finally to England, which is where she narrates her story. I listened to this first-person novel as an audio book, and I felt as if she were speaking directly in my ear. As might be expected, hers is a life with trauma and tragedy. Much is lost, much is broken. The overwhelming takeaway, however, is this is a portrait of a giant. She displays deep depths of intelligence, emotion, strategic foresight, and unshakeable determination. She is a canonical protagonist, but I should not focus too much on the individual, I suppose. For historical patterns are what emerge here, the interconnection of racism and capital, for instance, bonded in colonial power.

Similar statements could be made about the majestic second novel under consideration here, The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers. Except Jeffers illustrates those patterns up to the present day. And she gives us an ensemble cast, not a single evocative protagonist. Here we have intergenerational trauma, narrative loops that sting again and again. In print, this novel is 816 pages. My audio file said it would take 35+ hours at normal speed. I went a bit faster, but still ... it went slow.

It used to be, any novel that started with a family tree wasn't one that I would stick with. And Love Songs has no simple family tree. I couldn't re-create it without assistance from the PDF on the publisher's website.

So I said "ensemble cast," but it's clear as the novel goes along that all the various stories (love songs) spin around a single point, Ailey Pearl Garfield, who eventually finds her career path as a historian and starts to sort out and tell straight the layered and bumpy narratives of her ancestors who are of African, Creek, and Scottish descent. Quotations by sociologist and civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) recur throughout, as does stories about the prominent Black intellectual leader's life and influence. Intergenerational trauma limits, even destroys, many lives in Garfield's family, as well as nearly her own, though she connects enough dots and gets enough help in the end to break — for herself and potentially others — the painful system and cycle.

It's a novel that reads like an opera, at points, as the shock of violence and heavy fate intervenes. The just are not always rewarded, and the evil often thrive. As noted above, the action may begin in a murky past, but it is brought up to the present, so the sharpness of its historical critique is raw with contemporary detail. The historical patterns of era of enslavement continue to echo, and more than echo, mark lives in the day-to-day. Scholarly illumination of the hard facts is one solution highlighted in the novel. Another is the novel itself. Sad songs say so much. Hard as they can be, at times, to hear.

At the heart of each of these novels is a smart, strong, brave — all around remarkable — Black woman.

Fab. Next?