A few published book reviews, then a list of recent reading and responses.

From The Miramichi Reader:

The Left in Power: Bob Rae’s NDP and the Working Class by Steven High (2025)

elseship: an unrequited affair by Tree Abraham (2025)

The Canadian Shields: Stories and Essays by Carol Shields, edited by Nora Foster Stovel (2024)

Other reading:

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton (2022)

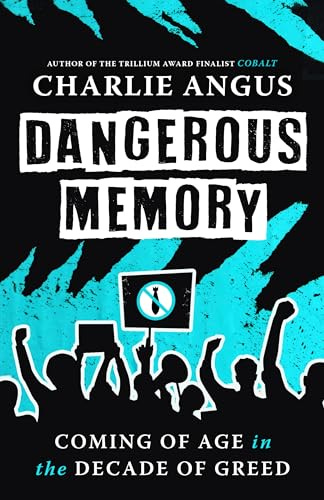

Dangerous Memory: Coming of Age in the Decade of Greed by Charlie Angus (2024)

The Flame Throwers by Rachel Kushner (2013)

The Hard Crowd by Rachel Kushner (2011)

Burn Book: A Tech Love Story by Kara Swisher (2024)

At the Full and Change of the Moon by Dionne Brand (1999)

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner (2024)

Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson (2007)

The Forty Rules of Love by Elif Shafak (2025)

Soroka by Corin Cummings (2025)

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot (1876)

The Blue House by Sky Gilbert (2025)

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (1849)

Let’s begin by noting the books I’ve already posted about here: all of the Kushner ones, plus Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson. Soroka by Corin Cummings and The Blue House by Sky Gilbert have reviews forthcoming in The Miramichi Reader. So that narrows the field.

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton (2022)

Dangerous Memory: Coming of Age in the Decade of Greed by Charlie Angus (2024)

Burn Book: A Tech Love Story by Kara Swisher (2024)

Each of these three is both a memoir and a portrait of an era, a time and place, and each is excellent in its own way. Kate Beaton’s graphic memoir, Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, has been repeatedly rewarded (“A New York Times Notable book! One of Barack Obama’s favorite books of 2022! Winner of Canada Reads 2023!”) — and deservedly so. It’s harrowing, and I’m sure I’ll never forget it. I started thinking, I wonder how she’s going to draw those monster trucks, and I finished it thinking, men are shit and how horrid is the violence so casually directed at women. Beaton tells of her journey from Cape Breton, where she finished university, broke, to Alberta to get the cash to pay off her student loans. It’s a journey many from “Down Home” trek, and she meets many from Atlantic Canada, ex-fish plant workers and others “Gone Down the Road.” It’s a deeply intimate portrait of her challenges and aspirations, while also capturing the weird world of the petrochemical “man camps.”

Charlie Angus, former Member of Parliament, former Catholic Worker House Coordinator, former punk rocker and ongoing member of The Grievous Angels, tells of his political and musical coming of age in the 1980s, the Decade of Greed.

Though Angus is more than a few years older than me, there’s a lot in this book that overlaps with my own coming of age in East Toronto. For one, the Catholic Worker House that Angus helped to found, near Greenwood and Queen Street East, was in a neighbourhood I know well. Plus all of the musical contemporaries he shared stages with were the bands I followed in high school, as the early 1980s coincided with the explosion of music television and the well named New Wave.

I read Angus’s book back-to-back with The Left in Power: Bob Rae’s NDP and the Working Class by Steven High. In spirit, they have a lot in common, though there are interesting differences. High knows the inner workings of government, how the gears of policy grind against stakeholder expectations and party politics. He is really good at explaining how the sausage is made, and the trade offs politicians often have to make — but also the great leaps they also some times pull off against all odds. Whereas Angus is a part theologian, full on punk rock activist. Though he shares none of Andrew Breitbart’s politics, he agrees with his maxim: "politics is downstream from culture" and that to change politics one must first change culture. His memoir is chock full of examples of artists, musicians mostly, pushing for—and achieving—political change.

Kara Swisher’s story starts where Angus’s leaves off, in the late-1980s, early-1990s, at a moment where the culture is shifting in many ways. Geopolitically, with the fall of the Berlin Way, and the collapse of Communism in Russia, indeed the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. But more significantly for Swisher, with the rise of the Internet — and ultimately, the tech bros. Burn Book: A Tech Love Story is Swisher’s love letter to the tech boom — and also its obituary. So much promise has led to so much destruction. So much optimism has sunk into a swamp of cynicism. “Information wants to be free” has morphed into the New Fascism. Swisher’s got it all. Elon’s spiral into chaos, and Steve Jobs surprising subtle moments—and vision—for humanity. I shook my head so much through this book. Remember Google’s “Do No Evil”? HAHAHAHAHA.

At the Full and Change of the Moon by Dionne Brand (1999)

The Forty Rules of Love by Elif Shafak (2025)

I wanted to like At the Full and Change of the Moon by Dionne Brand; I just didn’t. Why? Does it matter? It just seemed a weak version of Toni Morrison. I mean, it was okay, but I wanted more.

Elif Shafak’s The Forty Rules of Love was a book club pick. It was neat, pleasant, charming, organized, easy to follow, educational—it mixes a contemporary story with a story about the poet Rumi (1207-1273) about whom I knew next to nothing and now know a bit more.

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot (1876)

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (1849)

I took in these two expansive 19th century British novels as audio books, part of my ongoing project to catch up on the so-called Classics. I mean, I have two English degrees and there are still so so many books I feel like I ought to have read. These two are now off my to-do list. Both, in general, follow my dictum about British literature; they’re about, generally, the regulation of women. Though also about much else.

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot, um, I mean, okay. I’ve read a number of Eliot novels in recent years—Middlemarch, fantastic (and, yes, super long)—and I heard that Daniel Deronda was maybe her best. Not by my estimation. The novel has two converging stories, one about the title character, who slowly learns of his Jewish identity, and another about a young woman who marries foolishly because she wants to live the pampered life and then discovers she is miserable, superficial, trapped in an empty bubble of her own creation. I, for one, did not feel sorry for her. But a lot of ink is spilt explicating her troubles. There’s much sophistication in the writing, sure, but Jesus wept, this is definitely not punk rock.

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens, on the other hand, won me over in the end. I am not predisposed to enjoy—or admire—Dickens. And a lot of this novel is a lot of people talking nonsense, stupid British nonsense, the kind of nonsense that Monty Python skewered deliciously. Dickens skewers it, too, but again, Jesus wept, what a long bloodly novel of people quacking on and on about nothing. It was nice to finally meet Uriah Heap, though. Dickens was brilliant at creating characters molded around characteristics that give them All Star status. Heap is one of those, Ebenezer Scrooge another. Copperfield is apparently Dickens’s most autobiographical novel. It has a wonderful growth from beginning to end, expanding with the age of the title character. But what is going on with all of the love interests? David is hopeless in love—and hapless in understanding women. He is too much an observer, not enough a participant in his own life, perhaps. This enables the overall comic frame of the novel, I suspect. It’s quite a beauty—and my favorite Dickens yet.