A Hero of Our Time

by Naben Ruthnum

McClelland & Steward, 2022

A slacker with money. That's my take away — GenXer that I am — after trying to wrap my head around that mysterious character of 19th century Russian literature, the superfluous man. For examples, see Oblomov (1859) by Ivan Goncharov, "The Diary of a Superfluous Man" (1850) by Ivan Turgenev, and A Hero of Our Time (1840) by Mikhail Lermontov — and now also by Naben Ruthnum, 182 years later. (See interview with the author by Kathryn Mockler.)

From the Encyclopedia Britannica:

Superfluous man, Russian Lishny Chelovek, a character type whose frequent recurrence in 19th-century Russian literature is sufficiently striking to make him a national archetype He is usually an aristocrat, intelligent, well-educated, and informed by idealism and goodwill but incapable, for reasons as complex as Hamlet’s, of engaging in effective action. Although he is aware of the stupidity and injustice surrounding him, he remains a bystander. The term gained wide currency with the publication of Ivan Turgenev’s story “The Diary of a Superfluous Man” (1850). Although most of Turgenev’s heroes fall into this category, he was not the first to create the type. Aleksandr Pushkin introduced the type in Eugene Onegin (1833), the story of a Byronic youth who wastes his life, allows the girl who loves him to marry another, and lets himself be drawn into a duel in which he kills his best friend.

About the Lermontov novel, the Britannica says:

The novel is set in the Russian Caucasus in the 1830s. Grigory Pechorin is a bored, self-centred, and cynical young army officer who believes in nothing. With impunity he toys with the love of women and the goodwill of men. He impulsively undertakes dangerous adventures, risks his life, and destroys women who care for him. Although he is capable of feeling deeply, Pechorin is unable to show his emotions.

Ruthnum's novel is one of the strangest I've ever read. However, considering it in the context of these Russian novels, it starts to settle into a pattern, find its home as it were. I read the novel months ago, but it has retained a hold on me. A kind of, what the fuck was that? kind of hold. Is it a satire? Yes and no. Ironic? Yes and no. Absurd? Yes and no. Comic? Yes and no. Is it a portrait of a character emblematic of an era, e.g., Dostoevsky's Underground Man (1864)? Yes and no. Well, what is it then?

An attempt at a plot summary. SETTING: Early decades of the 21st century. LOCATION: Various. USA & Canada. PROTAGONIST: Osman Shah, not young, not old, Brown, not married, entangled with his colleague and occasional lover, Nena. ACTION: Focused on the internal (power) dynamics of an international enterprise that ... well, what does it do? It sells a system that enables online learning. It is an IT company? Sort of. An education/training company? Sort of. A blood sucking leviathan scraping intellectual property for capital? Something like that. In its marketing, the company positions itself as the solution to the problem of inefficient educational experiences, that is, the classroom. Take the experience online and outcomes improve. For example, suddenly real estate is not required, student engagement produces reams of data, profit margins soar. The satire nearly writes itself.

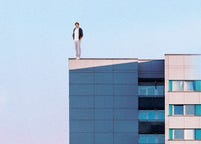

But what's that you say? So far it's all set up and no plot. Right then. As the novel opens, Osman, our hero, is drifting in his career, enjoying a well remunerated job without the drama that comes with "playing the game." That is, he is happily anonymous and invisible. Forget the notion of "bring your full self to work," Osman isn't sure he has a full self, and whatever of himself is real, it isn't on display in the office. "Work persona" hardly covers the extent of Osman's workplace performance. He is a disco ball in a hall of mirrors. A shadow's shadow. He is keenly aware of the power plays going on around him, but he has decided his best path to success (e.g., early retirement) is to avoid all of it. Until he falls under the gaze of Olivia Robinson, bright, young, White, power player extraordinaire. Meet our ANTAGONIST.

Story is sometimes described as a hero's journey to achieve a desired outcome, overcoming challenges along the way, particularly the barriers set in place by the villain, whose goal is to thwart the hero's progress. Ruthnum's A Hero of Our Time roughly follows this trajectory, but a lot of the time the picture presented is the inverse of what you might expect. It's like the world is suddenly viewed through a filter where all of the positives are now negatives. Shifts in perspective are required to recover reality, insofar as that's even possible. What does our hero want? To be left alone. To be invisible. To drift anonymously in the background. To not leave his mark on the universe. To be, in other words, not a hero. But Olivia Robinson gives him no choice.

The stakes are, let's be clear, low. He can remain invisible, accumulate significant (unearned, arguably) wealth, hide in quiet retirement. Or, take a more prominent role in the power dramas of the corporation and become even more significantly wealthy, opening up a future of whatever the hell he wants. The stakes are, however, existential. To be or not to be, that kind of existential. Does he remain himself, or is he, gasp, forced to change? Can he change? Is it even possible? Do we care?

For chunks of this novel I wasn't sure I cared, or I was sure I didn't care, or I actively wished he would fail. I wasn't sure Olivia was all that bad, initially. Everyone participates in the performative corporate speak, is she really the problem? Herself? But then, in the end, yes, she is.

Thinking about the novel, after finishing it, I kept wondering what kind of story is it. I thought of Kurt Vonnegut's graphs of story types.

I thought maybe Osman was a Kafka-type protagonist. He doesn't wake up and find out he's a bug, but his destiny is altered in the kind of arbitrary way that is neatly described as Kafkaesque. Still, he recovers his equilibrium ultimately in a way Kafka's leads do not, even as he's drawn in to the land of wild conspiracy and secret societies. Bizarre things happen, but then good triumphs over evil. At least momentarily. Osman ends up on COVID lockdown free at last from everyone, able to hide from the world, marinate in his loneliness. Oliva proves she’s a survivor and surges forward with corporate domination. Osman escapes her gravity, though, so achieves the outcome of his desire.

This book is curious in that it is filled with drama, and it is also anti-climactic. It's that odd mix that has kept it alive in my mind, though.

There are a number of themes and plot points I haven’t touched on here. The summary is already complicated enough, but I do want to note what the back cover calls “collectivist diversity politics.” Whatever you think that means, it’s probably not what is presented in the novel, but it’s clear that race-as-identity is deconstructed, examined, reanimated, and then spun around all over again as the novel goes along.

Another interesting sub-plot persists throughout: Osman's relationship to his family. His late-father was a university professor who was disappointed in him. Osman finds his father's memoir in draft on a computer, reads some of it, and then deletes it forever. His mother had given up a professional life to be a housewife, but then took on new roles later in life. Osman is concerned about her health and engages with her caregiver. He also reads long portions of his own life story into his mother's voice mail. Not only does she not listen to them, she breaks up with him. He visits to check in on her, and she tells him plainly that she doesn't want to see him again. Life is too short to spend another minute with him. He can hardly believe it, but he accepts it.

What one is to make of this, I don't know. These are shockingly powerful plot points, and they are consistent with the theme of "hidden identity." (An interesting compare/contrast between Olivia and Osman’s mother. Oliva wants Osman to reveal himself; his mother wants him to go away. Olivia says to Osman what he wants to hear from his mother, but it repels him.) The truth is out there, the X-Files said. Here, the truth is interior — and also never to be discovered. This harsh reality is probably more aligned with day-to-day experience. Most stories are about people working through obstacles to get closer together, achieve an element of intimacy. Osman has an "occasional lover," sure, but intimacy isn't what they achieve. Is Osman a hero of our time? The question hangs out there. Readers will have to decide for themselves.