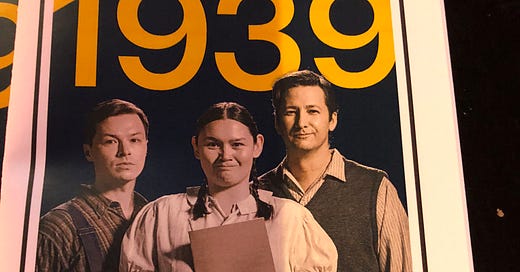

The drama titled, 1939, by Jani Lauzon and Kaitlyn Riordan premiered at the Stratford Festival in 2022. It is currently on at the Canadian Stage in Toronto, where I saw it two nights ago. Tomorrow is the National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, the day that honours the Survivors of residential schools, as well as their families and communities, and especially the children who never returned home.

As the London Free Press wrote of the 2022 production:

While Beth Summers (Tara Sky) stands centre stage as the lights dim at the end of the Stratford Festival’s 1939, the full weight of the play’s story falls on the audience like the final beat of a drum.

I mean, yes, absolutely.

At the same time, Monday Magazine says of the current production:

In the play 1939, humour is more than just a way to lighten the mood; it's a tool for survival, a way of fighting cultural assimilation and coping with the trauma of Canada's Residential School system.

Also absolutely, true.

The play’s the thing, and to play is to play. It’s fun, too, but deeply serious. Dropping a little Shakespeare there is to the point. The setting of the play, titled for the eve of World War II, is a residential school in Northern Ontario, which anticipates hosting King George VI, part of a planned Canadian visit. What will they do? Put on a performance of Shakespeare’s “All’s Well That Ends Well,” showcasing how the school is turning Indigenous children into “good little Canadians.”

All’s well that ends well. Consider those five words within the context of residential schools and their legacy.

So there is a play within the play, a mapping of colonialism onto Indigenous souls, but then there is also a play within a play within a play. The students find a way to Indigenize Shakespeare. They reimagine the roles, map them onto their own lives. The broader context is, of course, stark, and pointed violence of the residential schools is depicted but mostly off-stage. The cast brims with youthful enthusiasm, finding ways to remain true to their core selves, while showcasing the limitations, the outright cruelty of their situation.

They make the best of a bad situation, in other words, a situation that we contemplate now while wearing orange.

I didn’t do any research before I saw the play, but the did search afterwards. A question raised by J. Kelly Nestruck in the Globe and Mail was similar to one I left wondering:

But how effectively does 1939 dramatize the experiences of residential-school survivors, and is it an effective vehicle to do so at a time when reconciliation has pivoted toward reckoning and attention is being primarily paid to the location of unmarked graves?

I haven’t made up my mind about it, but also I don’t think it’s my question to judge. As Nestruck notes:

the play’s five-year development process has been, as the program says, “guided by Indigenous Elders, Survivors and ceremony.”

But still, is there too much Shakespeare? I’m not sure. Ultimately, the play centres the Indigenous voices — a diversity of them — and showcases resiliency over tragedy, while also acknowledging the lost ones. That’s a lot for a play to carry — and it does so gracefully.

The production was at the Canadian Stage’s Berkely Street Theatre, which is across the street, currently, from a construction site.

In the early summer of 1988, that site include a gas station, where I worked for about two months, often taking the overnight shift. I wrote a bit about this in my post SRV (1989):

For six weeks that spring I also worked at a gas station on Front Street, by the Toronto Sun building. The place had three eight-hour shifts, and I worked each of them, pumping gas. Most memorable was the overnight shift, 11:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m., where one could see the rhythms of the night. A busy flow of cars came after midnight, but then the streets became quiet, until the Toronto Sun vans started to arrive, stacked with the day’s papers, heading to out to stuff newspaper boxes around the city.

The drivers were also selling drugs. More than one asked me if I was interested. No.

One morning I arrived for the day shift and a pair of high-heeled shoes was on top of one of the gas pumps.

“What’s this?” I asked.

A car had pulled up in the night, my colleague said. A prostitute and a john. Some sort of altercation happened. They left, but the shoes got left behind.

“Can I have them?” I asked.

I knew a girl at school, notorious for her shoe collection. Later, I added to it.

The place was also robbed while I was there, but not on my shift. Or maybe it was robbed. Because the truth was, the ownership of the station had changed hands just before I arrived. A White family owned it and sold it to a South Asian family. One of the original owner’s sons continued to work there, pumping gas. He’s the one who claimed to have been held up. The South Asian owner was a young man, not much older than me. He could see I was a university kid, different from the others, and he asked me what I thought: Did I believe this story?

I shrugged.

As I was writing this, I remembered something else. One of the dudes I met at the gas station remembered me from public school.

“Are you Michael Bryson? From R.H. McGregor?”

I was. I am.

He told me who he was, and I thought, Holy shit. Yes. I knew him, too. He was a massive troublemaker, but I didn’t say that. (A troubled kid, surely.)

“What have you been up to?”

He looked about has haggard as my boss at the print shop. He had three kids, he said. He’d been doing this and that. Of course, he asked me what I was doing, and I said I had just finished my first year of university.

We had been kids together, but our lives were, even at that stage, very different.

One story I didn’t include in that earlier recollection involved a 15-year-old girl I didn’t meet. As I stood on the corner, trying to confirm that this was indeed the site of the gas station 36 years earlier (it was), I thought about an incident I’ve never forgotten.

It happened on one of the overnight shifts, maybe two or three in the morning. A car pulled up to get gas, and I started to fill it up. Then another car pulled in, and this guy got out, very manic, explosive with energy. He had a story and he wanted to share. He’d just gotten out of the hospital. It had been very bad. He wasn’t sure he was going to make it. He got out, then ….

“I just fucked a 15-year-old! I just got out of the hospital, and I fucked a 15-year-old!”

As I stood on the corner, I did some quick math. She would now be 51. I said a little prayer for her and hoped she was okay.

The memory revolts me.

The other thing that happened at that gas station that I didn’t mention earlier, is one weekend the Degrassi cast held a celebrity carwash. Was Drake there? No. He was on the show 2001-2008, apparently. Not my era!